« Previous Essay

Bruce Conner’s Mabuhay Punks

Next Essay »

Conner’s Films and Rauschenberg’s Filmic Time

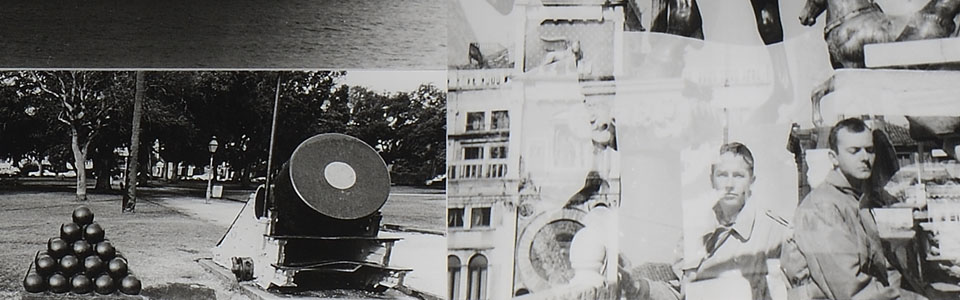

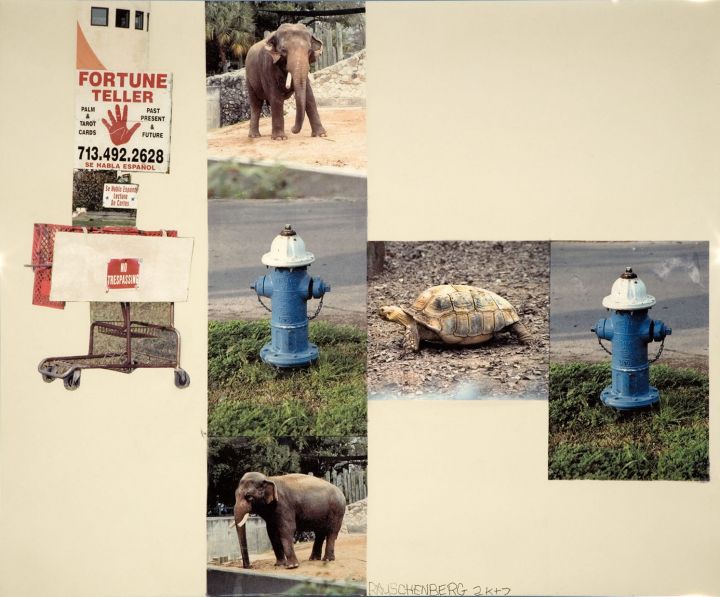

CAT. 83 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), Untitled, 1984 (detail)

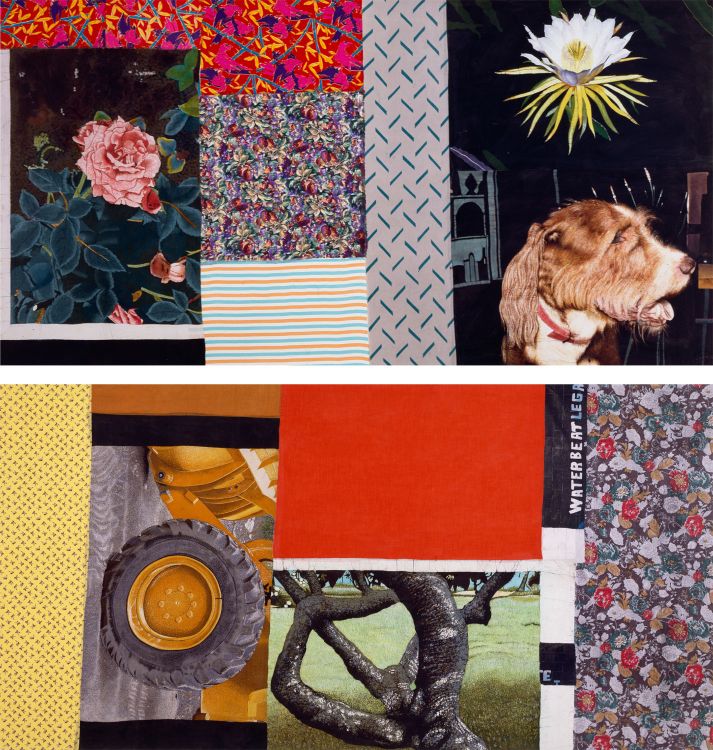

Robert Rauschenberg’s Untitled (Faux-Tapis) (CAT. 88) is an enormous, two-panel construction, one in a series of five that he realized in 1995. The work is comprised of batik fabrics collaged together with “false tapestries” created from the transfer of his own photographs onto cloth using a wax-based technique developed in a Sri Lankan batik workshop. He then bonded the various true and fake (vrai et faux) fabrics to aluminum supports. Close examination discloses the photographic transfers, or “faux tapis,” to be a large rose, a singular water lily, the trunk of a banyan tree, signage, the upended wheel of a bulldozer, and his dog “Kid.” Rauschenberg interspersed the rectangles of the faux tapis with both colorfully printed and solid batiks that he purchased on a trip to Sri Lanka in 1983. In this abstract patchwork composition, he juxtaposed the found batiks and the commissioned “faux” tapestries to ground the work firmly in two social realities: traditional Sri Lankan culture and everyday life in the United States.

CAT. 88 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), Untitled (Faux-Tapis), 1995. Collaged fabric on two bonded aluminum panels, 128 1/2 x 121 x 2 inches overall (326.4 x 307.3 x 5.08 cm). Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York, New York. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York.

Removing the found tapestries from their traditional context and function, Rauschenberg fabricated something “false” in the service of art, but created something “true” as art. Such conundrums are typical of his works, especially the many that incorporate photography. Photographs are inherently linked to an actual physical source while also separated from reality through the medium’s innate process of abstraction, a dichotomy that the artist exploited in his works. Careful not to imbue his art with pre-determined meanings or philosophical frameworks, he once declared to a studio assistant, “I never speak metaphorically.”1 In deliberately rejecting metaphor, Rauschenberg aimed to represent things as authentic in themselves. To achieve this end, he often altered the precise context of his imagery, challenging viewers’ ability to identify the image in a predictable way in order to emphasize things as they are.

Throughout his career, Rauschenberg used photography to explore the contradictory qualities of photographic representation in varied applications of the medium. He produced both stand-alone prints and developed his well-known transfer method in order to incorporate photographs in collages and on paintings, silkscreens, tapestries, ceramics, and metal. In his lifelong investigation into the possible uses and functions of the photographic image, Rauschenberg struck a virtuoso equilibrium between the documentary aspect of photographs (by imbuing his works with cultural and historical import) and the medium’s potential for abstraction (by manipulating images to alter pre-conceived meanings), balancing his photographic results between the medium’s inherent technological objectivity and his own subjective framing.

Moreover, although it has gone unremarked, Rauschenberg’s use of photography in paintings and Combines must be understood as a critical break from the visual conventions of the New York School of painters in so far as photography enabled him to alter the traditional attributes of both the picture plane and the object in the round. At the same time, his photographs fix things, places, and people relative to his own existential experience. In this sense, Rauschenberg’s exploration of photography may be said to connect to philosophical aspects of the abstract expressionist ethos, however much he staunchly denied existentialism in his work, distancing himself from its angst and criticizing artists’ self-pity.

This essay examines Rauschenberg’s varied utilization of the medium, as he relies on the documentary quality of photographs to depict personal, historical, and cultural context and meaning. Simultaneously, he recontextualizes, fragments, and abstracts reality to allow for a multiplicity of readings, which I explore through the unexpected lens of his concern with authenticity and its phenomenological relationship to Christian Existentialism.

The incorporation of photographs in Rauschenberg’s artworks serves to ground them in a certain place and time. Rauschenberg began working with photography at Black Mountain College in the summer of 1951. Enrolling in a seminar organized by photographer Hazel-Frieda Larsen, he was exposed to the work of visiting professors Harry Callahan, Arthur Siegel, and Aaron Siskind. Rauschenberg often acknowledged his debt to Larsen, though he was uninterested in her emphasis on the technical aspects of photography. Producing a traditional fine quality print was not his concern. “Perfection is not one of the goals,” he stated, “because it’s a dead end.”2

CAT. 63 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), Postcard Self-Portrait, Black Mountain (II), 1952. Gelatin silver print, 3 1/4 x 5 5/8 inches (8.3 x 14.3 cm). Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York, New York. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York.

In January of 1952, Edward Steichen purchased two of Rauschenberg’s photographs for the Museum of Modern Art in New York: Untitled (Interior of an Old Carriage) (1949) and Untitled (Cy on Bench) (1951). This purchase came six years before the institution acquired any of his other artworks. That summer, he returned to Black Mountain where he produced several photographic portfolios. During this period, Rauschenberg began asserting himself as an artist, discovering how he could make an original contribution to art through what he called “a series of self-imposed detours.”3 Postcard Self-Portrait, Black Mountain (II) (CAT. 63) of 1952 is his first self-portrait as a young artist. Lying on a mattress, lost in a moment of vulnerable self-awareness, Rauschenberg rests in front of one of his black paintings; light reflects from the floor to fill the lower two thirds of the image. The photograph communicates self-awareness and discipline, qualities of Rauschenberg’s existential state of being and consciousness.

Rauschenberg also photographed fellow Black Mountain student and artist Cy Twombly, as well as his work, helping Twombly to win a travel fellowship from the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. Twombly invited Rauschenberg to join him on his journey, and the two romantically involved artists departed for Europe in August of 1952, settling in Rome just before Rauschenberg’s divorce from his wife Susan Weil was finalized. While abroad, Rauschenberg continued to experiment with photography, bringing only a Rolleicord twin-lens reflex camera with him. The insightful pictures he took of Twombly in Rome are revealing biographically. In Cy + Roman Steps (I, II, III, IV, V) (see CAT. 60), Twombly descends the iconic marble stairs of the Basilica di Santa Maria in Aracoeli, a thirteenth century church on the highest summit of the Campidoglio in Rome. Rauschenberg’s photographic viewpoint remains relatively fixed from image to image, excluding Twombly’s head and his body, which occupies an increasingly large portion of the frame as he approaches the camera. In the final photograph, Twombly appears only from waist and crotch to upper thighs in an image that is sexually charged. This photographic window into Rauschenberg’s intimate personal history demonstrates his careful attention to Twombly’s body, gestures, and clothing, highlighting the individual perspective of one subject regarding another.

Upon his return to the U.S., Rauschenberg gave up photography in order to focus on painting. This decision would prove premature, as he explained in 1981:

Both of them [photography and painting] were total dedications. I decided that my next photographic project was to walk across the United States and photograph it foot by foot in actual size. I figured that in twenty years I would be in jail in Ashland for trespassing if I followed through with that idea. So I decided maybe I’d just go on painting. Then the paintings started using photographs. I’ve never stopped being a photographer.4

In retrospect, Rauschenberg’s fascination with and incorporation of photography in his work was only beginning, as he collaged media images and personal photographs alongside other various found elements in his Combine paintings.5 Rauschenberg relied on the solvent-transfer process as a means to include photographs in his work. This process remained central to his artistic concepts throughout his career, although he continually modified his transfer techniques with the invention of new technologies.

Rauschenberg frequently transferred found photographs to drawing paper by coating them with lighter fluid and rubbing the reverse side with a pencil. But by the spring of 1962, he began experimenting with printmaking at the invitation of Tatyana Grosman, founder of Universal Limited Art Editions (ULAE) in West Islip, New York, where Jasper Johns had been working since 1960. During this time, Rauschenberg began producing lithographs, transitioning to silkscreen paintings soon afterwards. His silkscreens feature images drawn from a variety of magazines, including National Geographic, Life, Esquire, Boxing & Wrestling, and he compiled a library of pictures, sorting them into various categorized files from which he selected photographs to be sent to commercial screenmakers. Determined not to confine himself to any one medium or style, Rauschenberg abandoned his collection of silkscreens after being awarded the International Grand Prize in painting at the Venice Biennale in 1964, finding other ways to incorporate appropriated photography into his art, and transferring images onto Plexiglas, fabric, metal, and various other materials.

Demonstrating a predilection for mass media imagery throughout the first half of his career, Rauschenberg’s dedication to taking his own photographs was not reignited until 1979, when he designed a set and costumes for Trisha Brown’s Glacial Decoy.6 He projected a series of his black and white photographs taken in Fort Myers, Florida, onto four screens at the rear of the stage. The soundtrack for the dance became the clicking of slides changing every four seconds. Reflecting on the experience several years later, Rauschenberg explained that in order to edit and select images for the dance production he had “to take approximately a thousand new photographs in a short period of time” and he “became addicted again” to photography, which “heightened” his “desire to look,” and became a “fertilizer to promote growth and change in any artistic project.”7 His “desire to look” underscores Rauschenberg’s eagerness to reproduce the truth and beauty that he perceived in the world. His experience with Trisha Brown and Co., combined with a growing concern for the liability of featuring found photographs in his works, eventually prompted Rauschenberg to turn to his own photographs, which he primarily used for the next twenty-seven years until his death.8

With his return to practicing photography, Rauschenberg directly confronted the challenge of passing time and how his pictures transformed an ephemeral existential experience into an eternal image. This aspect of his work is vivid in how he used the camera to document his travels. For example, in 1980, he bought a 1936 Phaeton Ford and spent a month driving from New York to Captiva Island, Florida, with his assistant Terry Van Brunt. Traveling less than forty miles each day, they frequently stopped for Rauschenberg to photograph in cities from Atlantic City and Baltimore to Charleston and Savannah. He titled his collection of these and other locales In + Out City Limits.9 Over a hundred of Rauschenberg’s photographs from this series, together with twenty-eight photographs taken between 1949 and 1965, were included in Rauschenberg Photographe, an exhibition organized in 1981 by curator Alain Sayag at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris. His high contrast photographs focus on the textures and details of ordinary objects: a towel hanging on a clothing line, the hull of a boat, the trunk of a tree painted white, a bucket on a floral tablecloth. Rauschenberg’s careful attention to light, shadows, the shapes of his subjects, and the qualities of their forms emphasize his effort to capture the genuine conditions of the world around him.

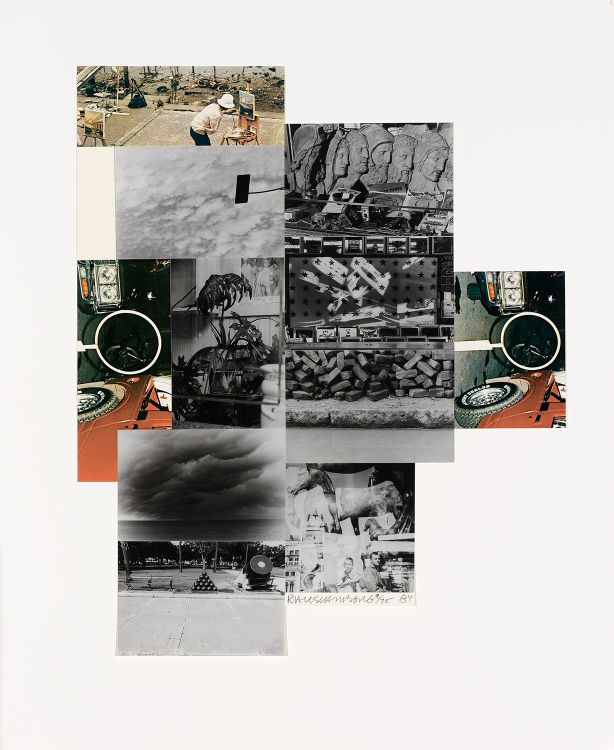

CAT. 83 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), Untitled, 1984. Screenprint with fabric and photo collage on hand-cut paper, edition 9/75, 31 7/8 x 26 3/8 inches (81 x 67 cm). Collection of the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina. Gift of Blake Byrne (T’57), Susan and David Gersh, Bea Gersh, and Carol and David Appel; 2006.9.1. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York. Photo by Peter Paul Geoffrion.

Untitled (1984; CAT. 83), a collage of fabric and images on hand-cut paper, features photographs from his travels with Twombly in 1952, interspersed with others from Rauschenberg’s In + Out City Limits project. In the bottom right, the pair appears in a double exposure taken in Venice that Rauschenberg accidentally superimposed over a photograph of ancient spolia from Constantinople, Byzantine columns, and Renaissance towers. The collage emblematizes a formative moment in both the artists’ cultural and interpersonal experiences in Europe. Such works narrate and index both intentional and unintentional autobiographical references to his existential experience of the period.

According to Barbara Rose, “Rauschenberg’s art extends a moral tradition of the artist as witness, functioning as time capsules, a composite of what he witnessed not in a single place or country but on television, in newspapers, and in his travels all over the world.”10 His morality is perhaps most evident in his creation of the Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange (ROCI) in 1984, a project through which he would collaborate with artists in eleven different countries, concluding in 1991 with an exhibition at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.11 Throughout his travels, Rauschenberg constantly amassed “an ever-growing archive of images”12 that reveal his achievement in documenting new environments and bridging cultural gaps, especially in politically unstable regions. This strong impulse to serve the world recalls his Christian Fundamentalist upbringing and background. Although Rauschenberg stopped attending church by 1960 and no longer claimed to be affiliated with any particular Christian denomination, he practiced what he understood as his social and spiritual responsibility to lead an authentic life in his role as an artist witness.

fig. 17 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), Canto XXX: Circle Eight, Bolgia 10, The Falsifiers: The Evil Impersonators, Counterfeiters, and False Witnesses from the series Thirty-Four Illustrations for Dante’s Inferno, 1959–60. Transfer drawing, watercolor, gouache, and pencil on paper; 14 1/2 x 11 1/2 inches (36.8 x 29.3 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York. Given anonymously. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York.

This position is clear in comments he made in 1965 on his “34 Drawings for Dante’s Inferno” project: “The one thing that has been consistent about my work is that there has been an attempt to use the very last minutes in my life and the particular location as the source of energy and inspiration, rather than retiring to some kind of other time, or dream, or idealism.”13 With its picture of an astronaut, echoing Rauschenberg’s fascination and future involvement with NASA, Canto XXX (1959–60; fig. 17) of the Dante drawings exemplifies his effort to imbue his art with social import, translating Dante’s Inferno into a genuine representation of the period and the artist who made it.14 His own comment here suffices: “I always wanted my works — whatever happened in the studio — to look more like what was going on outside the window.”15

Continuing to produce art with a distinctly international perspective, after 1991, he virtually abandoned his older methods of image transfer and transitioned to newer technologies, using an Iris inkjet printer to produce digital color prints with biodegradable vegetable dyes and then transferring them to paper using water and an electric press. Utilizing this transfer process in photographic works for the remainder of his life, Rauschenberg reached new levels of cultural mediation evinced by works like the fresco painting Contest (Arcadian Retreat) (1996; see CAT. 89). Contest includes transfer photographs that he took on a trip to Turkey and that picture contemporary Turkish culture in the midst of the famous ruins at Ephesus and Cappadocia.16 These photographs of the nation’s glorious past mingle in the urban landscape: a Turkish sign reads “Merdal Business Center”; colorful soccer balls jostle with a basketball; laundry hangs on a line; and the renowned Library of Celsus at Ephesus (ca. 117 CE) shares the fresco with the Manhattan Municipal Building, recognizable by its gilded statue, Civic Fame, designed by Adolph A. Weinman.

The subject matter of Contest represents a mixture of different geographical locales and shows Rauschenberg’s methods of blending the ancient with the contemporary in order to offer a visual synthesis of historical epochs. Such works justify Jaklyn Babington’s description of Rauschenberg as “a cultural archeologist [and] a master of collecting, editing, and assembling the imagery of society, the environment, life, and time.”17 Rauschenberg, nonetheless, countered his impulse to document his environment by attending to the inherent abstraction in picture taking. In the case of the Arcadian Retreat series, Rauschenberg’s use of an unconventional plaster canvas reminds viewers that the medium, despite seemingly capturing reality, is actually an abstraction of one — just as carefully fabricated as a traditional fresco painting.

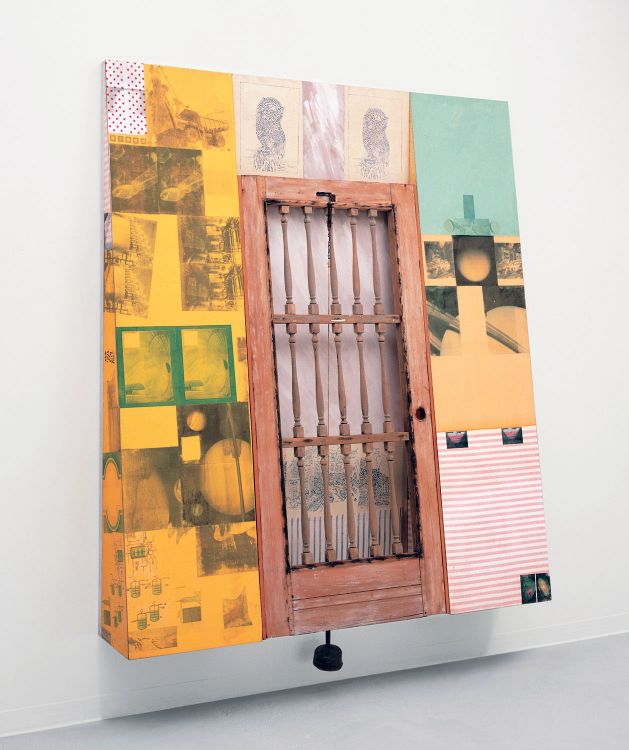

CAT. 82 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), Solar Elephant (Kabal American Zephyr), 1982. Solvent transfer, fabric collage, acrylic, wood door, wood mallet, metal spring, and string on wood support; 104 x 83 x 15 3/4 inches (264.2 x 210.8 x 40 cm). Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York, New York. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York.

In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes insists, “A specific photograph, in effect, is never distinguished from its referent (from what it represents), or at least it is not immediately or generally distinguished from its referent.”18 Barthes asks his audience to take into account the processes of framing, lighting, exposure, printing, and cropping, emphasizing that even the most straightforward photograph is always an abstraction of reality. Rauschenberg considered the process to be even more direct. “What you see in front of you is a fact,” he commented. “You click when you believe it’s the truth.” He went on to note that “information is waiting to become in essence a concentration . . . [that] can be projected back into real life, into your recognition.”19 Despite his inclination to evoke a strenuously reliable image of reality, albeit highly condensed, Rauschenberg’s photographic truth lent itself to abstraction through the processes of transference, recontextualization, juxtaposition, and fragmentation, and his insistence to actively involve viewers in the creation of a work’s meaning.

The solvent-transfer process that he employed for much of his career is a form of abstraction itself. As Rosalind Krauss explained, Rauschenberg’s “unified stroke” and the “act of rubbing” created “slippage between one image and the next.” She concludes that the “rubbing’s visual blur promotes the sensation that the images are ‘veiled.’”20 The curator and photographer Van Deren Coke amplified this process when he observed that playing upon “the tension between the real and the illusory. . . . Rauschenberg is willing to raid this real world to introduce fragments of it and the illusion of stereometric depth to his paintings and prints — not for their own sake — but for comparison.”21

CAT. 90 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), Meditative March (Runt), 2007. Inkjet pigment transfer on polylaminate, 61 x 73 1/2 (154.9 x 186.7 cm). Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York, New York. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York.

Rauschenberg also removed photographs from their normative context, juxtaposing them with a variety of other objects, images, and materials. This is especially evident in such works as Solar Elephant (1982; CAT. 82), a Combine containing a found wooden door with a hanging wooden mallet between two wall-like structures. Newspaper and magazine clippings, as well as photographs, cover the work’s surface like wallpaper to create an entirely fictive realm of people, animals, planetary forms, hydraulic diagrams, and five paint- or embroider-by-number panels of cloth. Rauschenberg continued such methods of recontextualization in his final series, Runts (2007), drawing upon his own encyclopedic archive of photographs, transferring seemingly unrelated images onto polylaminate synthetic material mounted on aluminum panels, and juxtaposing surprising images that provoke new associations. The press release for the exhibition exclaimed: “Rauschenberg has replaced the eye of mass media with his own.”22

CAT. 86 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), Wild Strawberry Eclipse (Urban Bourbon), 1988. Acrylic and enamel on galvanized metal and mirrored aluminum, 84 3/4 x 193 x 2 inches (215.3 x 490.2 x 5.1 cm). Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York, New York. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York.

This new approach, coming late in his life, is vivid in Meditative March (2007; CAT. 90), also from the Runts series. Here Rauschenberg brings together photographs of elephants, an image of a turtle, fortune telling signs, a no trespassing sign, and photographs of a blue fire hydrant. Laurence Getford, Rauschenberg’s former studio assistant, noted that when Rauschenberg was unable to move about freely in his later years, he dispatched his assistants with cameras, instructing them to take photographs of “uninteresting things,” emphasizing his belief that “the unimportant was as important as the important.”23 The eclecticism of Meditative March is the result of such a process. Without any discernable narrative, Rauschenberg leaves “room,” in his words, “for everyone’s imaginations to create meaning.”24 Encouraging a multiplicity of readings, he asks viewers to take responsibility for the act of interpretation, thereby engaging in a moment of aesthetic freedom. Indeed, while on tour for ROCI, he told an audience in Japan: “The function of art is to make you look somewhere else — like into your own life — and see the secrets that are in the shadows, or in the way the light falls somewhere.”25

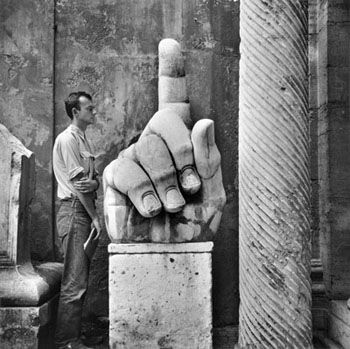

CAT. 59 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), Cy + Relics, Rome, 1952. Gelatin silver print, 15 x 15 inches (38.1 x 38.1 cm). Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York, New York. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York.

Turning to metal as a canvas, Rauschenberg took this approach one step further by physically reflecting viewers in the works. Wild Strawberry Eclipse (1988; CAT. 86) brings onlookers closer to their own lives through mirroring. Reconnecting the existential gap, Rauschenberg unites subject and object on the shiny, silkscreened, enameled, mirrored, and anodized aluminum surface of the brightly colored painting with its expressionistic brushstrokes. Wild Strawberry Eclipse includes his own photographs, many taken in Cuba, such as a closed pair of shutters, a group of laborers, the rear end of a station wagon, and a line of laundry. Becoming part of his Cuban experiences, viewers enter Rauschenberg’s world and interact in an abstract existential encounter.

Rauschenberg also emphasized the abstract act of photographing by dissecting the boundaries of the photograph itself. The same afternoon that he photographed Cy + Roman Steps, he also captured Twombly in the courtyard of the Palazzo dei Conservatori in Cy + Relics, Rome (CAT. 59). Twombly stands awe struck by the massive hand severed from a sculpture of Emperor Constantine in the courtyard of the palazzo. The formal structure of the photograph frames Constantine’s fragmented hand as it is measured against Twombly’s body on its left with an ancient Roman column on its right. Rauschenberg’s contact sheet attests to the fact that he took several exposures of Constantine’s hand without Twombly in the frame. Each one is shot at an increasingly greater distance in order to incorporate more of the surrounding environment in his investigation of temporal and spatial fragmentation.

Thinking about Rauschenberg’s work, Walter Hopps once wrote: “To capture time is to fracture time.”26 In many of the artworks examined above, Rauschenberg utilized photography to do just that.27 In this regard, the medium of photography could be said to relate to existential philosophy since the photograph “reproduces to infinity [what] has occurred only once,” as Barthes would explain, adding: “The photograph mechanically repeats what could never be repeated existentially.”28 This fact prompts Barthes to declare: “Death is the eidos [or essence] of photography.”29 The photograph as a self-conscious preservation of a subject, who threatens to disappear, is deeply related to its inherent existential dilemma of representing something always already lost.

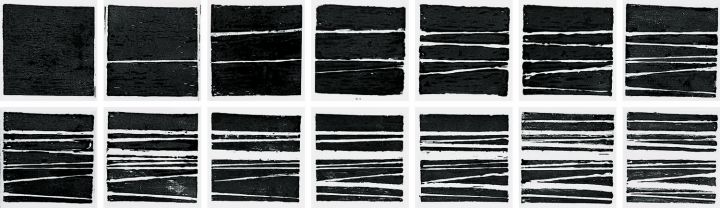

fig. 18 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), This Is the First Half of a Print Designed to Exist in Passing Time, 1948. Pencil on tracing paper and fourteen woodcuts on paper, bound with twine and stapled; 12 1/8 x 8 7/8 inches each (30.8 x 22.5 cm). Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York, New York. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York.

In this way, despite his strong rejection of the negativity of existentialism, a relationship exists between Rauschenberg’s use of photography throughout his oeuvre and the existentialism of many abstract expressionist artists. For while it is true that he challenged the verticality of abstract expressionist work through what Leo Steinberg theorized as his “flatbed picture plane,”30 and he created what others would theorize as a “different order of experience,”31 Rauschenberg’s use of photography must be understood to link to the work of his predecessors, even as it simultaneously laid the foundation for an entirely different perspective on art.

Philosophical existentialism exists in many different forms. Although the French philosopher Gabriel Marcel coined the term in the twentieth century, the nineteenth-century Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard is considered to be the philosophical father of existentialism, even if it was Jean-Paul Sartre’s interpretation that dominated the post-war period.32 The foundational concepts of existentialism — that existence precedes essence, that an individual lives in a state of free will, and that one is responsible for determining one’s own fate — have the capacity to create meaning in a meaningless world. Following World War II, existentialism was instrumental in the analysis of individuality, freedom, anxiety, authenticity, and death. Existentialism also became the lens through which to define the highly expressive abstract painting associated with European Art Informel, as well as figurative sculpture and painting by artists like Alberto Giacometti and Francis Bacon, and eventually American abstract expressionist work. Under the influence of Sartre’s emphasis on the free, autonomous individual, the art critic Harold Rosenberg framed “action painting,” especially that of Jackson Pollock, as an existential “encounter” with the work as a form of self-realization.33 Even the influential French art critic Pierre Restany would observe: “It was difficult not to see Pollock as an Existentialist at the time.”34

This point of view was precisely the sort of “existentialism” that Rauschenberg vehemently sought to avoid. “I’m never sure what the impulse is psychologically,” he insisted, “I don’t mess around with my subconscious. . . . If I see any superficial subconscious relationships that I’m familiar with — clichés of association — I change the picture.”35 Rauschenberg further asserted that it was “extremely important that art be unjustifiable.”36 In an interview with Dorothy Seckler, he remembered during his first few years in New York that he was in “awe of the painters,” but he also “found a lot of artists at the Cedar Bar . . . difficult . . . to talk to,” as he was “busy trying to find ways where the imagery and the material and the meanings of the painting would be not an illustration of [his] will but more like an unbiased documentation of [his] observations.”37

Rauschenberg’s determination to rid his work of any ascription of philosophical existentialism has been highly successful, with many prominent artists, critics, and art historians taking him at his word. In 1961, John Cage wrote: “Perhaps after all there is no message [in Rauschenberg’s work]. In that case one is saved the trouble of having to reply.”38 Two years later, clearly following Cage, Alan Solomon in the catalog for Rauschenberg’s 1963 retrospective at the Jewish Museum declared: “There are no secret messages in Rauschenberg’s work, no program of social or political discontent transmitted in code, no hidden rhetorical commentary on the larger meaning of Life or Art, no private symbolism available to the initiate.”39 Moreover, whatever existential challenges Rauschenberg experienced in his life, he flatly refused to dwell on them, and he had little patience for those who did. In 1987, Barbara Rose told the artist: “You’ve never done depressing art.” Rauschenberg answered, “I hate it.”40

Rauschenberg’s distaste for psychological self-analysis was motivated by a desire for the pursuit of joy in his life rather than interrogation of the past. He expressed this characterological trait early in life. While aspiring to become a preacher in his youth, he relinquished this aim when he discovered that his fundamentalist denomination forbade dancing and playing cards. “I just wasn’t that interested in sin,” he said years later, “I don’t like negative input.”41 Nevertheless, Rauschenberg remained involved in organized religion for many years. In the fall of 1948, he painted a scene for the newly constructed baptistery of his parents’ church;42 and he continued to attend services of different religions during his first few years in New York. He also characterized much of the work he showed at the Betty Parsons Gallery in May of 1951 as belonging to a “short lived religious period.”43 While most were lost in a fire, the works that remain include Crucifixion and Reflection (1950), Mother of God (ca. 1950; see fig. 3), 22 The Lily White (1950), and The Man with Two Souls (1950). Mother of God particularly evinces Rauschenberg’s spiritual journey, which he renewed again and again, long after he left organized religion, in his renowned generosity and service to others.

Rauschenberg’s spirituality may best be compared to Christian Existentialism, especially as he expressed aspects of Christian values in his choice of projects. A comment on why he initiated ROCI is a good example: “I don’t think it came from religion,” he stated. “I think it came from caring.”44 However, “caring,” as a spiritual imperative, originates in the West in the “Golden Rule” preached by Christ in his Sermon on the Mount: “All things whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them.” This commandment parallels earlier Mosaic law: “Whatever is hurtful to you, do not do to any other person.” Thus does duty toward one’s fellow beings reside at the core of the Abrahamic religions, with the commandment to “love thy neighbor,” a particular aspect of Christian teaching. Although Rauschenberg gave up the idea of a religious calling, Leo Castelli, Rauschenberg’s long-time art dealer, commented on the artist’s impulse in organizing and carrying out ROCI. “Bob once wanted to be a preacher,” Castelli noted, concluding: “he is a preacher still.”45 Walter Hopps also identified Rauschenberg’s deep humanity: “He loves with such equal intensity: men, women, children, dogs, trees, rocks . . . all of life.”46

In the context of his photography, Rauschenberg’s care culminated in his return to a decidedly religious subject in 1996 when he accepted a commission by the Vatican to create a work to commemorate Padre Pio of Pietrelcina, the Capuchin Catholic, who, after dying in 1968, was sainted for his corporeal physical manifestation of the stigmata. Rauschenberg’s work on the Padre Pio project was to be installed in the architect Renzo Piano’s Padre Pio Pilgrimage Church, or Shrine, in San Giovanni Rotondo, Italy. Rauschenberg worked on designing a photographic collage for its massive stained glass tympanum, using an innovative new transfer process that he was developing in collaboration with Bill Goldston at ULAE.47

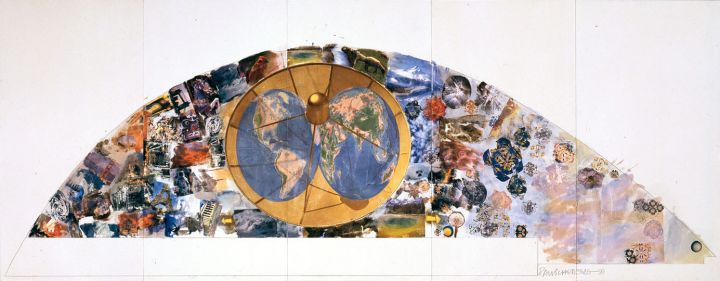

fig. 19 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), The Happy Apocalypse, 1999. Inkjet pigment transfer, acrylic, and graphite on polylaminate; 96 x 250 x 2 inches (243.8 x 635.2 x 5.1 cm). The Menil Collection, Houston, Texas. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York.

A small-scale prototype of the work, entitled The Happy Apocalypse (1999; fig. 19), made from inkjet pigment transfers of photographs onto a polylaminate surface, shows that Rauschenberg drew inspiration from the Book of Revelation. The left side of the work contains images of storms, hurricanes, tidal waves, and fragments of monuments, including the Eiffel Tower, Westminster Abbey’s Big Ben, and the Statue of Liberty. According to Rauschenberg, these images were meant to evoke “fragments [and] memories of manmade monuments in destructive transformation,” and to convey the magnitude of loss suffered during the apocalypse.48

In the center of the work, Rauschenberg placed a photograph that he took of a satellite dish, which he purchased, brought to his compound on Captiva Island, and had painted gold. Topped by a diagram of the world, the golden satellite dish represented Rauschenberg’s idea of an all-knowing God; and he called the satellite dish “the tool or symbolism of spiritual wisdom.”49 The right side of the mockup for the tympanum exudes a “quieter pastoral energy phasing into crystalline of spiritual reality,” with photographs of flowers, trees, rocks, waves, mountains, clouds, animals, and planetary forms interspersed with expressionistic strokes of pale blue, pink, and orange paint.50 When a Franciscan prior, who was involved with the project, suggested that Rauschenberg would be a Catholic by its completion, Rauschenberg dryly responded: “And I suppose you’ll be an artist.”51

In a 1997 Vanity Fair article on the artist, art historian John Richardson remarked: “While [Rauschenberg] is a spiritual man, he is no believer, and he intends to steer clear of overt religious references.” Rauschenberg’s unique interpretation of the biblical apocalypse is evidence that, despite working with the Catholic Church, his spirituality remained unaffiliated. That he pictured God as a gold satellite dish was anything but blasphemous. On the contrary, it seems to have been Rauschenberg’s way to create a “Happy Apocalypse” rather than a dire end to the world. But that unconventional image of the Christian God would lead to the demise of his involvement in the project.

A letter from Renzo Piano to Rauschenberg in November 1997 predicted the unfortunate end. Piano warned Rauschenberg against pursuing his idea of a “positive Apocalypse” or “Apocalisse Allegra,” as it might “offend Monsignor Crispino Valenziano,” their Vatican coordinator, who, the architect diplomatically explained, was a “very sensitive man.”52 Piano was correct: Valenziano rejected Rauschenberg’s representation of God as a satellite dish and requested that the artist incorporate the Madonna into the piece instead. This pedestrian request was too much for Rauschenberg to bear. On February 5, 2000, he responded in a letter that testifies to Rauschenberg’s critical acumen, his sense of humor, and most of all his insight into Monsignor Crispino Valenziano’s lack of imagination.

“What were halos?” Rauschenberg asked the Monsignor, “Fashion or stylistic acceptable affectations of antiquities to celebrate the extravagance of the sponsor or the holiness of the biblical story?” After his opening salvo, Rauschenberg got to the point:

Contemporary symbolism has to follow and change with the recognizable experience. The antenna is communication and mystery of the miracle of the “all knowing” with the majestic aura of the halo. It is boundless, encircling the world inspired by all space.53

Completing these two brief paragraphs, Rauschenberg put the letter down without signing it. The following day, Rauschenberg returned to his letter, adding the date — February 6, 2000 — under the paragraph that he wrote the day before, and continuing:

After overnight deliberation, I came to the following realization and conclusion; this is my opinion: I feel that God is born inside of each one of us. My God does not use wrath, threats, revenge or heavenly bribes to control or to teach justice, compassion, and goodness. I am disqualifying myself from this holy project. I am either spiritually under- or over-qualified.54

With this letter, Rauschenberg asserted his refusal to reduce the ubiquity of God to halos or the Madonna when his aim had been to show that “souls are unworldly radiances moving into holy infinity,” that God is a benign being “born inside each one of us,” and that in the twenty-first century the “mystery of the miracle of the ‘all knowing’” is manifest in the omnipotent surveillance of the satellite dish. Rauschenberg abandoned his four-year-long project, but not before adding a pointed reference to the lack of ethics of the Church. Writing that he hoped to “work with Renzo in the future without moral compromise,” Rauschenberg more than implied that the Church had pressured him to concede his artistic integrity and right to represent the munificence and deific omnipresence of God in the way that he saw fit.

Rauschenberg closed the letter and, with it, his association with the Vatican. He was, he wrote, “eternally grateful to have been selected by the Vatican Commission and to be associated with the miracles of Saint Pio.” He signed his letter: “You all have my love.” Rauschenberg’s letter demonstrates his undeniable moral superiority in his insistence upon standing for the right for every generation to represent its concept of God according to its beliefs and its era. That Rauschenberg put aside a project to which he had given some four years of his life affirms his spirituality, something akin to Christian Existentialism in its expression of commitment, generosity, love, and joyous embrace of humanity over which an omniscient God prevails like a satellite dish!

CAT. 77 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), Untitled (Hoarfrost), 1975. Solvent transfer on fabric, and fabric collage with cardboard; 83 x 49 1/4 x 6 1/2 inches (210.8 x 125.1 x 16.5 cm). Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York, New York. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York.

Rauschenberg’s unwavering attitude toward God very much aligns with Kierkegaard’s religious construal of existentialism. Kierkegaard understood routinized State Christianity as an obstacle to living an authentic life, for its promotion of passivity over a passionate declaration of belief.55 Authenticity represented the ideal of becoming “true to the originality of one’s own being in spite of societal or cultural obstacles.”56 In a Christian elucidation, Kierkegaard referred to this routine of conformity as the “leveling” of mass-culture and modern society, and urged individuals to undergo the “laborious task of facing reality, making a choice and then passionately sticking with it.”57 In this Kierkegaardian sense, Rauschenberg pursued an authentic life in his refusal to compromise his beliefs and in his sense of personal responsibility.

Rauschenberg rarely addressed politics directly in his art, commenting that he “never thought that problems were so simple politically that they could, by me anyway, be tackled directly.”58 By the end of the 1960s, he did, as Roni Feinstein observed, “shift his focus from local concerns . . . to a broader involvement with American politics and society,” and finally “to an engagement with global issues, international cultures and the state of the world.”59 His increasing interest in the world at large could be said to embody concepts of how one arrives at existential freedom through action that itself emerges from alienation and anxiety.60 The German philosopher Paul Tillich was among those who theorized Christian Existentialism based in concepts of “anxiety” defined as “the state in which a being is aware of its possible nonbeing.”61 Tillich continues: “It is not the realization of universal transitoriness, not even the experience of the death of others, but the impression of these events on the always latent awareness of our own having to die that produces anxiety.”62 Thus, an underlying knowledge of and anxiety concerning death represents a critical element of existential struggle.

CAT. 62 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), Rome Flea Market (III), 1952. Gelatin silver print, 15 x 15 inches (38.1 x 38.1 cm). Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York, New York. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York.

Although he did not explore death explicitly, Rauschenberg certainly did so implicitly, as if coming to terms with his own anxiety. This is best demonstrated in the Hoarfrost series of the mid-1970s, with its evocation of the transience of both nature and the photographic image.63 He first encountered the word “hoarfrost” in the late 1950s while reading Dante Alighieri’s Inferno, the first part of his epic poem The Divine Comedy (1308–21). Rauschenberg was enchanted by how the natural phenomenon of frost heralds a sometimes subtle and sometimes dramatic change in the seasons. Over a decade later, he arrived at the idea of the Hoarfrost series when he noticed how the cheesecloth that he used to clean lithographic stones retained newsprint images from the transfer-printing process. Drawing an analogy between the fleeting morning hoarfrost and the specter of images that he printed on the cotton gauze, silk chiffon, and satin fabric, Rauschenberg called attention to the fragile life of images that disintegrate over time. He also captured this transience in Rome Flea Market (III) (1952; CAT. 62), picturing a tarpaulin’s rough, tattered surface, and acutely visualizing its decaying and damaged material, as if the tarp was death itself. This sensitivity to death comes through again in Combine paintings like Canyon (1959) and Monogram (1959) with their taxidermied animals suggesting “the absent body” described by Lisa Wainwright: “[ I ]t is our body evoked, our humanity questioned, our impending death wishfully forestalled, our sublime unknowing fetishistically unfulfilled.”64 Finally, in The Happy Apocalypse, Rauschenberg devoted himself to the afterlife, an action that expressed a form of anxiety about life’s ephemerality, at the same time as it embodied and summoned memory of Tillich’s advocacy of “the courage to be.”

CAT. 55 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), Quiet House—Black Mountain, 1949. Gelatin silver print, 15 x 15 inches (38.1 x 38.1 cm). Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York, New York. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York.

At the beginning of his artistic life, Rauschenberg took up a camera to picture the touching beauty and silence of Quiet House — Black Mountain (1949; CAT. 55). A site of meditation, Quiet House was built as a memorial to Mark Dreier, a nine-year-old boy killed in 1941 in an automobile accident. He was the son of Black Mountain faculty members Theodore and Barbara Dreier. Eschewing the emotionally charged environment, Rauschenberg pictured sunlight on chairs and the texture of the rough cement wall. Light permeates the space, transporting viewers into the existential spiritual moment when he pointed his camera at an otherwise ordinary scene to reveal its extraordinary presence.

“I have never believed in just one possibility,” Rauschenberg said, “there are always polarities.”65 While I have argued that Rauschenberg’s photographs both possess and access his innate existential states of being, his art evades any reductionist theory. Still, his intense morality, ontological anxiety, and concern for authenticity are irrefutable. More poignantly, his relentless quest for joy betrays his pain. These aspects of the artist are most vivid in the extraordinary reach and application of photography in his art. Robert Rauschenberg produced culturally informed, historically grounded, highly abstracted, existentially charged, and spiritually driven works of art that call into question the meaning of art in the life of the artist, and artifice and veracity in the service of life and art itself.

« Previous Essay

Bruce Conner’s Mabuhay Punks

Next Essay »

Conner’s Films and Rauschenberg’s Filmic Time