« Previous Essay

Four Brodsky and Utkin Etchings and Rauschenberg’s Fresco Contest

Next Essay »

The Oracle in the CARDS: Robert Rauschenberg, Bruce Conner, and Michael McClure

CAT. 65 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), Self-Portrait [for The New Yorker profile], 1964 (detail)

The importance placed on artists’ identity and authorship dates to Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1568). Robert Rauschenberg and Bruce Conner sought to undermine the enduring emphasis in art history on artists’ lives long before the critique of biography began in the 1970s. Both artists rejected the concept of a fixed identity and its artistic correlate in authorship, and enjoyed unseating predictable ways of interacting with and interpreting their art. They turned to conceptual strategies to supplant conventional notions of identity and authenticity, anticipating the advent of conceptual art. Both worked in a wide range of mediums and resisted all categorization. Conner early rejected being identified with either assemblage or film, while Rauschenberg rejected efforts to view his art first through the lens of his biography. Approaching these questions in very different ways and through different means, Rauschenberg and Conner arrived at similar ends, redirecting viewers away from the artist to the artwork without ever simplifying consideration of the work in only formal terms.

Conner intentionally complicated the process of categorization; once he became known for one medium, he would switch to another. He also faked his death several times; hired a surrogate, Henry Moss, to stand in for him in public events; and launched a brief and irreverent foray into the political arena by running for a public office in 1967, a position he never intended to hold. Conner also often refused to have his photograph taken and even sometimes declined to sign his works. His anxiety about being photographed stemmed from his desire to watch undetected as viewers reacted to his art.1 In obscuring his identity, Conner tried not to interfere with the communication of his art, commenting: “The work should represent itself alone. [. . .] The insistence on displaying conspicuous names on works is an interference.”2 He continued, “The personality of the artist is a limiting factor in the function of the works. It predisposes people because they know the person or the economics of their place in the art world in relationship to another artist.”3 The art historian Kevin Hatch recognized this point in his aptly titled book Looking for Bruce Conner. “It is clear,” Hatch wrote in measured understatement, “the artist enjoyed countering expectations and exposing shibboleths.”4

While Rauschenberg made no attempts to hide his identity, he changed his first name in 1947 “from Milton to Bob (subsequently Robert) after considering the most common names he could think of while sitting all night in a Savarin coffee shop.”5 In this regard, it could be said that Rauschenberg shed his past for an unknown but anticipated future, rarely looking back. Furthermore, after living in New York for some twenty years, he boldly moved to Captiva Island, Florida, in 1970. Far from the putative center of the art world (just like Conner, living in San Francisco), Rauschenberg then continued to produce highly original art, using new materials and technological processes, and confounding the ability of many to keep abreast of his enormous production in silks and satins, metals and ceramics, frescos and cardboards, as well as prodigious inventive use of his own accomplished photography. For his part, Conner considered the New York art world’s inbred self-importance to expose its provincialism, sarcastically stating, “If it is not in New York, it is ‘not seen.’ It is not taken seriously unless it has come to New York.”6

I am aware of the irony of seeking to unpack a topic that plunges the study into the very territory that Rauschenberg and Conner resisted. Yet, in what follows, I attempt to navigate their individual explorations and shared interest in identity and authenticity without falling into the biographical trap.

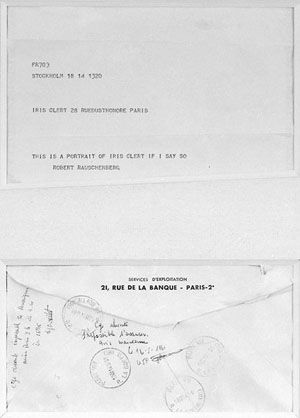

fig. 12 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), This Is a Portrait of Iris Clert If I Say So, 1961. Ink on paper with two paper envelopes, 17 1/2 x 13 5/8 inches (44.5 x 34.6 cm). The Ahrenberg Collection, Switzerland. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York.

In 1961 when French gallery owner Iris Clert invited artists to submit a portrait of her for an exhibition at her gallery, Robert Rauschenberg sent the following telegram:

THIS IS A PORTRAIT OF IRIS CLERT IF I SAY SO.

Clert, a “black-haired beauty who used to carry around little stickers reading ‘Iris Clert, the world’s most advanced gallery,’ which she would affix to people’s hands or clothing at parties,” clearly sought a portrait by the vivacious, handsome Rauschenberg to display along with the other artists’ pictures of her.7 But his telegram called into question the art historical tradition of portraiture to which Clert was bound, switching the emphasis from the sitter and the artist’s visual moniker to Rauschenberg’s refusal to serve the patron in the manner expected. That Rauschenberg merely “forgot” to make the portrait, as Calvin Tomkins reported, is beside the point.8 That Rauschenberg insisted on his conceptual dictate — text as portrait — is the point. Asserting concept over image, Rauschenberg overturned normative art historical dictates and conditions of a portrait.9

Whether or not in 1961 Rauschenberg knew Marcel Duchamp’s defense of Fountain, the commonplace urinal he turned upside down in 1917 and signed “R. Mutt,” is doubtful but open to question. Nonetheless, Duchamp’s point resonates with Rauschenberg’s telegram to Clert:

Whether Mr. Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view—created a new thought for that object.10

Rauschenberg first saw Duchamp’s work in 1953 but did not meet him until 1960, and John Cage, having met Duchamp in the 1940s, may have tutored Rauschenberg about Duchamp’s art. Nevertheless, Rauschenberg came to his own radical positions on his own even if he had absorbed the significance of Duchamp’s insistence on the authority of the artist over the work. In 1951 at the age of twenty-five, for example, Rauschenberg precociously anticipated his influence in art history when he painted his White Paintings (see CAT. 58), monochromes that brought him in 1953 to his ask for, receive, and then erase a drawing by Willem de Kooning (see fig. 7), another unprecedented action. In such works, Rauschenberg established his artistic prowess to name rather than to be a name.

Eight years after Rauschenberg’s telegram to Iris Clert, the French philosopher Michel Foucault would write, “Name seems always to be present, marking off the edges of the text.”11 In his essay “What is an Author?” Foucault further argued that readers, not the author, determine the meaning of a text: “It is a very familiar thesis that the task of criticism is not to bring out the work’s relationship with the author, nor to analyze the work through its structure, its architecture, its intrinsic form, and the play of its internal relationships.”12 Foucault continued:

An author’s name is not simply an element in a discourse; it performs a certain role with regard to narrative discourse, assuring a classificatory function. Such a name permits one to group together a certain number of texts, define them, differentiate them from and contrast them to others.13

While Foucault troubled the context of the author, Rauschenberg seized the opportunity — as an artist — to command that this IS a portrait of so-and-so, “If I say so.” His radical act of authorial authority underscored the purpose, perhaps even the duty, of the artist to construct the structure, architecture, intrinsic form, and internal relationships of a work of art, and the obligation of the viewer to interpret it.

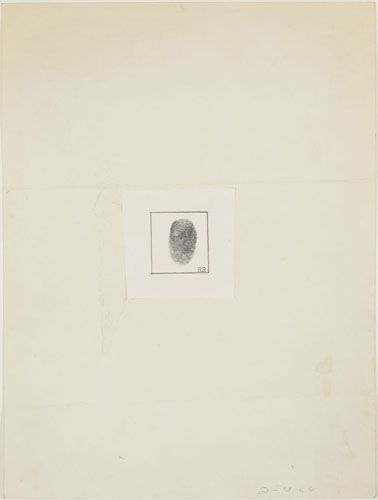

CAT. 65 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), Self-Portrait [for The New Yorker profile], 1964. Ink and graphite on paper, 11 7/8 x 8 7/8 inches (30.2 x 22.5 cm). Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York, New York. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York.

Rauschenberg pressed this idea in another direction in 1964, when the New Yorker magazine did an extensive profile article on him. Again challenging the conventions of portraiture, Rauschenberg gave the magazine his thumbprint as a “self-portrait.” Only three years after his telegram to Iris Clert, Rauschenberg’s thumbprint continued to comment on the status of what is, and who determines, a portrait and, thus, an identity. By submitting his thumbprint, Rauschenberg also updated the ancient concept of a picture of the face as the marker of uniqueness. This brought portraiture in conversation with forensics, as well as with institutional practices of the state, from the police and the penal system to the military. In this regard, Rauschenberg may have slyly nodded to his then-criminal identity in the early 1960s as a bisexual. That said, while a thumbprint is a distinctive characteristic of the body, no two thumbprints are the same; and while the print may be an index of a unique individual, the thumbprint reveals nothing about selfhood, personality, character or the distinctive qualities that make a person an individual.

The very same year that the New Yorker article appeared with Rauschenberg’s thumbprint, Bruce Conner had been busy discovering a plethora of people in the United States named Bruce Conner. He then began to think of a way to unite them all:

I had collected about 14 Bruce Conners so I thought we’d have a convention, hire a hotel ballroom. On the marquee it would say WELCOME BRUCE CONNER. You would walk in and get a button that said, “Hello! My name is Bruce Conner,” and you would have a program with a person named Bruce Conner who would introduce the main speaker, whose name was Bruce Conner.14

In preparation for the convention that never was, Conner commissioned buttons to be manufactured reading, I AM BRUCE CONNER (CAT. 10) and I AM NOT BRUCE CONNER (CAT. 9). Shortly after making the buttons, Conner delivered some I AM NOT BRUCE CONNER buttons to a gymnasium in Los Angeles named “Bruce Conner’s Physical Services.” Conner also sent Christmas cards containing both buttons to all of the Bruce Conners that he had found in the U.S.

Bruce Conner (1933–2008). Offset lithograph on metal pin buttons. left to right CAT. 10 “I AM BRUCE CONNER” BUTTON, 1964 (issued 1983). 1 1/4 inches diameter (3.2 cm). Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina. Promised gift of anonymous donor, L.13.2012.26. CAT. 9 “I AM NOT BRUCE CONNER” BUTTON, 1964 (issued 1967). 1 1/2 inches diameter (3.8 cm). Collection of the Conner Family Trust, San Francisco, California. © Conner Family Trust, San Francisco, California / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, New York.

Conner continued his own investigation into what may only be described as ubiquitous anonymity by refusing to sign anything for three and a half years. Then in 1965, he used his thumbprint to authenticate fourteen prints that he made at Tamarind Institute, a lithography studio and workshop in Albuquerque, New Mexico. “I couldn’t sign anything,” he stated, “but I would put my thumbprint on it which I considered to be a more authentic documentation of the artist than his signature.”15 According to Jean Conner, “While at Tamarind, Bruce took the largest stone there and printed his thumb print. The prints were then signed with his thumb print so the thumb print is the reverse of his signature thumb print.”16 As art historian Jack Rasmussen comments, “The intrusion of an artist’s signature, or signature style, [are] documentations of the artist’s ego and should not alter the viewer’s experience of the work of art. In fact, it [keeps] viewers from being able to look at work with a fresh eye, to be surprised at something truly new.”17

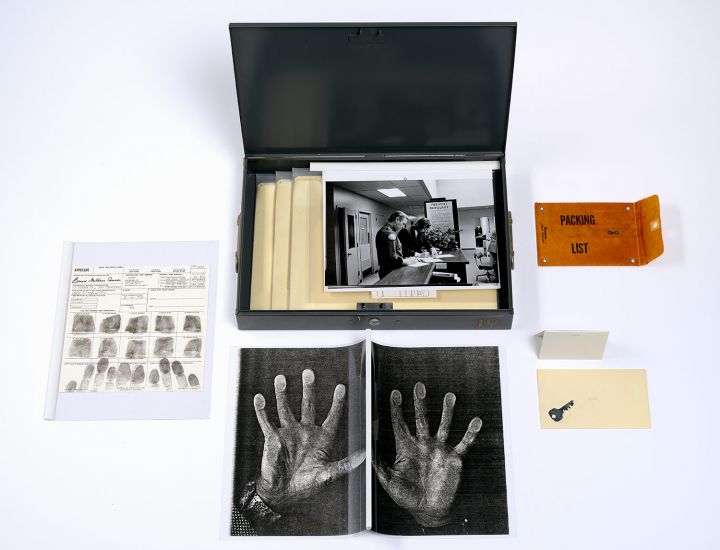

Nine years after authenticating works with his thumbprint, Conner was offered a teaching job at San Jose State College (now University), but predictably unpredictable Conner became furious when required to submit fingerprints to finalize his appointment.18 However, after considerable dispute with both the college and the state, he finally agreed to be fingerprinted at the Palo Alto police station. Many conversations, meetings, and memos later, as Joan Rothfuss explains:

[F]ollowing the fine-art model, a limited edition of twenty sets of fingerprints was produced at the Palo Alto Police Department, printed on official police forms, and signed by Conner in the box labeled “signature of a person fingerprinted”. In 1974 they became part of the multiple PRINTS [CAT. 22], a steel lockbox containing copies of correspondence, receipts, forms, and photographs related to the incident.19

More specifically the lockbox includes: correspondence with California State College administrators; correspondence with faculty in the Art History Department at San Jose State College; a receipt from the payroll supervisor confirming reception of Conner’s fingerprints; Conner’s official fingerprints; and photographs of both of Conner’s hands, among other images and objects such as the key to the box and its waxed envelope.

CAT. 22 Bruce Conner (1933–2008), PRINTS, 1974. Steel lockbox, paper envelopes with typewritten text, photocopies on paper, black-and-white photographs with typewritten text, metal keys, plastic bags, clear plastic folders with plastic binding clips, paper folders, fingerprint form, ink fingerprints; edition 19/20; box closed: 2 3/8 x 16 x 10 1/2 inches (6 x 40.6 x 26.7 cm). Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina. Promised gift of anonymous donor in honor of Kimerly Rorschach, 2013.14.1. © Conner Family Trust, San Francisco / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, New York.

One letter in the box is to art historian Kathleen Cohen, then Chair of San Jose State College’s Department of Art and Art History. In the letter dated December 10, 1973, Conner expresses his hesitation about the college’s fingerprinting policy. “This appears to mean that the fingerprints are solely a tool for gaining information for determining my capabilities as a teacher of art in the one Spring Semester of 1974,” he cautioned.20 Here Conner calls attention to the inherent irony of using a physical mark to determine one’s fitness for a position. He continues to substantiate why he is stipulating that his fingerprints must be returned to him after his period of employment and why he is insisting that his prints have immense value:

My fingerprints have a value in themselves as works of Art. Unless they are sold or leased under agreement with me then they can not be reproduced without my permission. Their value has to be secured against loss or damage. My own copyright for the fingerprints will be filed with the Library of Congress.21

Conner hyperbolically states that he will copyright his fingerprints with the Library of Congress to make a point, insinuating that they are so valuable that they merit their own copyright so no one else can use or copy them. Conner takes his fingerprints’ inextricable link with his identity one step further to declare that the prints do not only define him as a person, but they also authenticate the art he creates. As such, he should have complete control over who has access to the prints: “I control the use of my fingerprints, an absolute means of identification, as a means of absolute definition of my art.”22

The metal lock box also contains several photographs documenting nearly every step in Conner’s fingerprinting process. One photograph taken by the art dealer and gallerist Paula Kirkeby depicts Conner standing next to Police Officer Don Simerly. The photograph captures the moment that Conner and Officer Simerly sign fingerprint forms at the Palo Alto Police Station. The most prominent aspect of the photograph is the large sign behind them that states in all caps PREVENT BURGLARY. Conner no doubt included this photograph in the lock box for how the sign justified his argument about and resistance to being fingerprinted as if he was a criminal rather than an artist taking a teaching position.

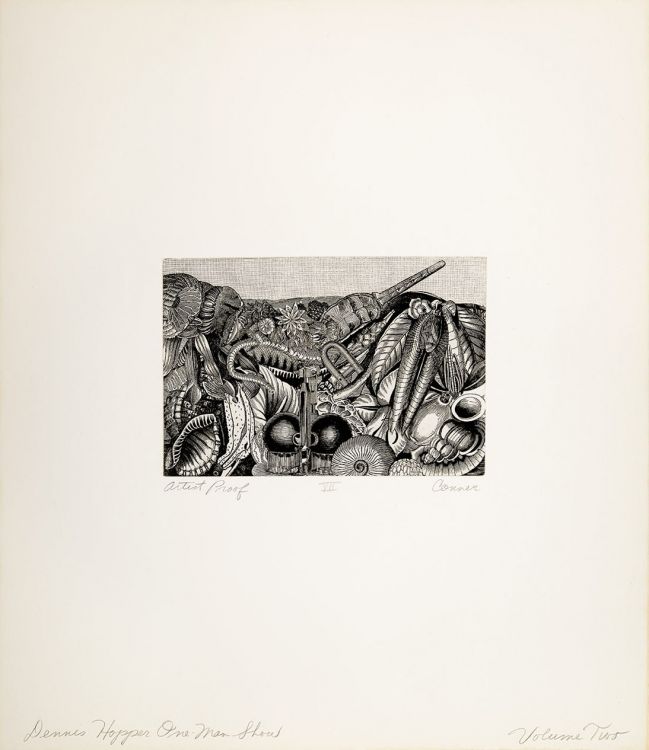

CAT. 21 Bruce Conner (1933–2008), THE DENNIS HOPPER ONE MAN SHOW, VOLUME II, NO. 7, 1972. Etching on paper, artist’s proof, 20 1/4 x 17 5/8 x 1/2 inches (51.6 x 44.8 x 1.1 cm). Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina. Promised gift of anonymous donor, L.13.2012.5. © Conner Family Trust, San Francisco, California / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, New York.

Another example of Conner’s mercurial exploration of identity began after meeting the actor and artist Dennis Hopper in 1960, with whom he established a lifelong friendship. In 1959, the year before their meeting, Conner had begun working on collages that included imagery from nineteenth-century wood engravings, which would eventually become what Conner called THE DENNIS HOPPER ONE MAN SHOW (1971–73). An example of one of the prints in this series is THE DENNIS HOPPER ONE MAN SHOW, VOLUME II, NO. 7 (CAT. 21). In this work, Conner creates a surreal universe constructed predominately from images of fauna and flora recalling scientific botanical illustrations. Conner performed his collage technique with such dexterity that transitions between images are nearly undetectable. These works call to mind the German surrealist artist Max Ernst’s collages for how unexpected juxtapositions intensify the possible associations suggested in the constructed reality. In addition, Conner’s precise unification of forms in collage parallels his exacting discipline in editing film.

Eventually Conner proposed to the Nicholas Wilder Gallery in Los Angeles that it exhibit the works under Dennis Hopper’s name. Attributing the work to Hopper, Conner sought to address the actor’s performativity and the fact that he made his living by impersonating fictive or real characters. By accrediting the works to Hopper, who had not made them, Conner further stipulated that the works would only become genuinely Conner’s own when Hopper himself walked into the gallery and encountered “his own” art, which in fact it was not. That moment of paradoxical surprise would produce authentic, surreal-like aesthetic experience. Wilder apparently was not amused, and refused to exhibit Conner’s series under Hopper’s name. Later, Susan Inglett explained another aspect of the engraved collages: they would only be “resurrected . . . as an artwork and as foil for a larger conceptual project [when] Conner returned the collages to their original printed state, producing twenty-six etchings bound in three black leather volumes and titled collectively THE DENNIS HOPPER ONE MAN SHOW VOLUMES I–III.”23

Thus, the DENNIS HOPPER ONE MAN SHOW underscored Conner’s interest in how the work of art might trump its author. That is, as long as he could get away with the prank or, more to the point, as long as he could tolerate the anonymity. Conner’s interventions into originality, authorship, identity, and role-playing must be seen to have anticipated discourses related to postmodern identity, summarized by the literary critic Homi K. Bhabha as “the struggle for the soul of the subject.”24 Conner certainly encouraged the enactment of multiple identities that would come to be associated with postmodernism, already questioning the unitary concept of a soul and the master narrative of fixed identity. The cultural theorist Stuart Hall also described how the postmodern subject is one that “assumes different identities at different times, identities which are not unified around a coherent ‘self.’”25

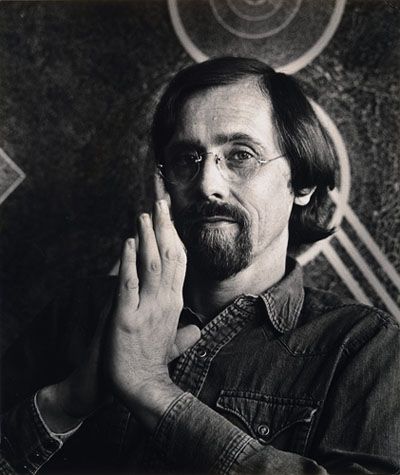

CAT. 37 Mimi Jacobs (1911–1999), Untitled (Photo of Bruce Conner), 1975. Gelatin silver print, 12 x 10 inches (30.5 x 25.4 cm). Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina. Promised gift of anonymous donor, L.13.2012.39. © 2014 The Estate of Mimi Jacobs.

A comment by Conner on the restrictions of the art world seems to expand on Hall’s observation: “There are different people in a single person,” Conner explained, adding that “the art business has been functioning on the absurd requirement and expectation that only one personality can be present in an artist.”26 Commenting on Conner’s position, Hatch observes: “To take Conner on his own terms, it is necessary to consider both aspects of his persona — the prankster, toying with artistic identity and convention, and the meticulous and earnest creator of exquisitely finished artworks — and further, to understand the latter in terms of the former.”27 A portrait photograph taken by Mimi Jacobs (CAT. 37) visually illustrates Conner’s complexity for how the portrait captures his intense probing eyes, as well as his whimsy.

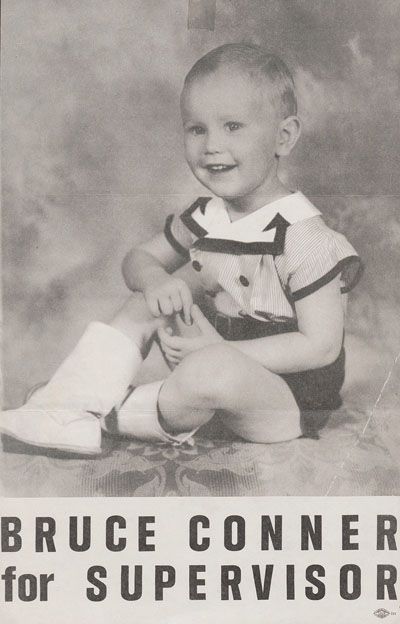

Conner’s prankster side is vivid in two works of ephemera he produced. In his 1967 spoof of a political bid for San Francisco Supervisor, Conner made a campaign poster that featured him as a toddler. Other publicity stunts included a poster showing him painting an elephant in a psychedelic pattern with the word LOVE on its side, and the public performance of his satirical “election speech,” which was a recitation of a list of desserts. This metaphorical commentary surely mocked the sugarcoated rhetoric of politicians. Another example of a playful and penetrating double entendre was the enigmatic bumper sticker he designed in the fall of 1972 for his exhibition at the Nicholas Wilder Gallery, which simply read: 1972 B.C.

CAT. 20 Bruce Conner (1933–2008), BRUCE CONNER for SUPERVISOR, 1967. Poster, 11 1/2 x 7 1/2 inches (29.2 x 19.1 cm). Collection of the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina. © Conner Family Trust, San Francisco, California / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, New York.

Simultaneously altering and avoiding a unitary identity, Conner firmly believed that “freedom implied the possibility that many selves with conflicting ideas could reside within the same consciousness.”28 This sentiment highlights Conner’s insistence on remaining illusive, like quicksilver. That Conner did not always appear coherent conforms to the fact that he did not always feel himself to cohere. While acutely aware of and knowledgeable about himself, Conner constantly fluctuated between being in and out of control. An instance of how he regulated his world is his meticulous process of drawing mandalas (see CAT. 14, #100 MANDALA). At the same time, Conner also seemed to careen like a car without breaks, perhaps best expressed by his activities in punk clubs in the late 1970s and early 1980s when he photographed and participated in that raucous scene in San Francisco (see essay “Bruce Conner’s Mabuhay Punks”). Despite swings of personality, Conner’s abiding sense of irony and extremely astute intelligence held his work — and him — in check.

In a 1990 interview, Conner told the writer Robert Dean: “If I were to attempt to define what I was doing, I [would be] putting a limitation on the work.”29 Similarly, according to David White, senior curator at the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, Rauschenberg “never defined his work because then it would be terminal.”30 As a means to avoid the end of his art, in 1984 Rauschenberg launched the Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange (ROCI). He began traveling internationally to work with and learn from local artists and artisans, expanding his canvas to include the world. Travel permitted Rauschenberg to involve himself critically in other cultures.31 Rauschenberg had always related curiosity to the expression of one’s identity. But he came to realize this more fully while traveling in China, where he was shocked by the isolation of people and their seeming lack of curiosity. “Without curiosity, you can’t have individuality. It just doesn’t exist,” he opined, adding that, “without curiosity or individuality, you’re not going to be able to adjust to the modern world.”32

CAT. 19 Bruce Conner (1933–2008), “1972 BC” BUMPER STICKER, 1972. Print in colors on paper, adhesive backing, 3 5/8 x 12 inches (9.2 x 30.3 cm). Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina. Promised gift of anonymous donor, L.13.2012.35. © Conner Family Trust, San Francisco, California / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, New York.

While working in Chile for ROCI, Rauschenberg learned how to use metal as a canvas for paint, tarnishes, enamel, and screen-printed images, resulting in paintings like Litercy (1991; see CAT. 87) from his Phantom series. Mirroring the surrounding space, as well as the viewer, the image on the metal constantly changes. In Litercy, he experimented with cropping, enlarging, and angling to transform several images into a montage such that the original photographs lose their temporal and spatial specificity. This mirrored reflective surface, with its swaths of brushed on tarnish, draws the viewer directly into Rauschenberg’s world, signified by the words “Bob’s Hand” and a pointing finger, almost as if Rauschenberg repeats the message of his telegram: “. . . if I say so.”

While he insisted on his authority, a comment Rauschenberg made in 1965 complicates this reading. “I was busy,” he said, “trying to find ways where the imagery and the material and the meanings of the painting would not be an illustration of my will but more like an unbiased documentation of my observations.”33 Even this comment is multifaceted. Taken literally, it means exactly what the artist often repeated: he wanted to create images reflective of the world rather than influenced by his mode of observation. But considering the fact that Rauschenberg provided not only a multidimensional visual experience in Litercy, but also a textual distortion in the misspelling of the work’s title (which should have been “literacy”), it is possible to understand that together word and image have a destabilizing impact on the reception of the work. Providing multiple layers of deformation, Litercy draws unsuspecting viewers into the visual and verbal world of Rauschenberg’s lifelong struggle with dyslexia, thereby introducing his unusual mode of seeing and knowing.

Long before his dyslexia was discovered, Rauschenberg developed an early negative self-image derived primarily from his difficulty in school where he was considered not very bright and even expelled from college. Only later did he come to realize his disability and, typical of Rauschenberg, worked hard to improve his reading and spelling. Nevertheless, he remembered that the painter Jasper Johns was “often critical of things like my grammar.”34 Poignantly, Rauschenberg explained: “But you don’t let a thing like that bother you if you have only two or three real friends.”35 Clearly Rauschenberg was hurt, and worked even harder to improve himself. Viewing first drafts of his handwritten letters prove this point. Although the ideas he expresses are complex and communicated in an eloquent, poetic way, his handwritten letters are full of numerous spelling mistakes, suggesting how tortuous it was for him to write.36 Moreover, a separate sheet of paper that correctly lists all his misspelled words accompanies many of his handwritten letters.

This archival material proves Rauschenberg’s determination to learn from and correct his own mistakes, painstakingly looking up words and trying to memorize their correct spelling. But the fact that he received the “Outstanding Disabled Achiever Award” from First Lady Nancy Reagan in 1985, just six years before permitting himself to use a misspelled word in the title to his painting Litercy, suggests that his notorious sense of humor and joie de vivre also allowed him to comment ironically on his own literacy, namely his inability to read and write with ease. Subverting not only his imagery but also his words, Litercy is not only a painting but also a picture of how Rauschenberg conquered his own disability, simultaneously drawing viewers in and helping us to experience his augmented vision of the world.

Though Conner was not dyslexic, he was acutely aware of the ways in which the mind processed words, stating: “I didn’t have much faith in words. They seemed to get twisted around a lot and I had more faith in vision. I had the assumption that visual information could not be denied or distorted as easily as words.”37 As the dyslexic writer Philip Schultz, who, like Rauschenberg, only learned the diagnosis of his disability in adulthood, explains: “The act of translating what for me are the mysterious symbols of communication into actual comprehension has always been a hardship to me.”38 Schultz continues, “I was suffering the mysterious, perplexing, and previously unacknowledged manner in which I received and absorbed all information of any import.”39 This understanding of the dyslexic led Ken Gobbo, a specialist in dyslexia and autism, to hypothesize that Rauschenberg’s dyslexia “may have allowed him to see the possibilities of incorporating the objects of his every day life into his art.”40 In his own words, Rauschenberg explained:

It is my own personal psychosis that it is only by the background that you can see what is in front of you. Only by accepting all that surrounds you can you be totally self-visualized. And at the same time, your self-visualization is a reflection of your surroundings.41

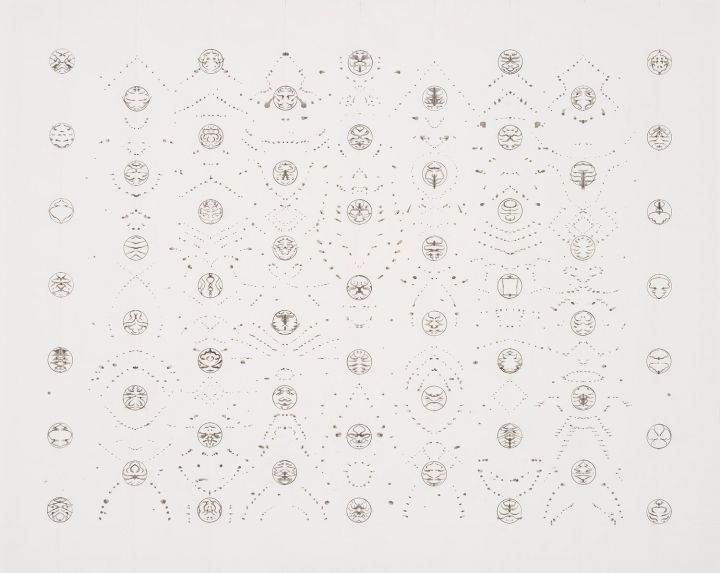

While Rauschenberg’s voracious appetite for materials and for documenting and visualizing the world around him resulted in his expansive imagery, Conner’s often-detached inward focus (particularly on his drawings) resides at the other end of the spectrum. Hatch attributes Conner’s drawings to what he calls the “anxieties that haunted him: his fears of being ‘pinned down,’ labeled, reified.”42 Peter Boswell reckons with the complexity of Conner’s drawings in a different way, writing that Conner “thrive[d] on ambiguity, on an elusiveness based not on an unwillingness to commit, but on an all-embracing aspiration to transcend specificity, espousing instead the notion that change and metamorphosis are essential components to life and art.”43 But a third view of Conner’s drawings, one closer to my own, is that of Jack Rasmussen, director and curator of the American University Museum at the Katzen Arts Center. Rasmussen writes about Conner’s INKBLOT drawings: “His works communicate on a subliminal level. They surprise and seduce our eyes, while causing us to question our own beliefs and values.”44 When asked about the INKBLOT works, Conner stated, “The goal is to get people closely involved in the works and to make works that are intimate. They require the viewer to move into the drawings.”45 To this I would add, that Conner’s aim — like that of Rauschenberg — was also to include the viewer, which is precisely what the INKBLOT drawings do.

CAT. 3 ANONYMOUSE (Bruce Conner) (1933–2008), INKBLOT DRAWING, JULY 25, 1999, 1999. Pencil, pen, and ink on Strathmore Bristol paper; 23 1/8 x 29 inches (58.7 x 73.7 cm). On loan from the Nancy A. Nasher and David J. Haemisegger families in honor of Peter Lange, L.2.2014.31. © Conner Family Trust, San Francisco, California / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, New York.

The carefully controlled INKBLOT drawings entail tiny detailed renderings of abstract images that highlight the artist’s technical expertise. Such meticulous, repeated patterns invite viewers’ deep contemplation. In fact, they request endless psychological involvement, as their complexity constantly reveals new relationships and associations. When asked about the physical process of making inkblots, Conner stated: “It’s determined ahead of time where the inkblots will be placed and organized. A ruler is used to mark out the pages and an implement to score the paper. Sometimes it starts as preplanned, but then it may be altered very soon after the process starts.”46 This sentiment further illustrates how Conner permitted himself to be in and out of control and to embrace both discipline and spontaneity.

The INKBLOT series also calls to mind the Swiss Freudian psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Herman Rorschach, who developed the Rorschach Inkblot Test. In this test, a subject is show ten inkblots one after another and asked to describe the objects or figures in each. Rorschach theorized that the test could measure, or at least access, unconscious aspects of the personality that an individual projects onto stimuli in the world. Conner intended for viewers of the INKBLOT drawings to project their unconscious ideas and emotions onto his work in tandem with the thoughts and desires that prompted the drawings. The result bound Conner’s vision to the psychological projections of viewers, enabling them to make associations both about the image and their maker.

“A picture is more like the real world when it is made from the real world,” Rauschenberg once said.47 Conner felt a similar connection to the world when constructing assemblages, stating: “There’s a point in time when I started self-consciously gluing down the world around me and making it mine.”48 Asserting their authority as the author of the work from diametrically different positions, Rauschenberg and Conner both arrived at results that demand intense engagement from the viewer. Conner first drew inward to focus viewers psychologically on themselves in order to create their own individual meanings, always inevitably related to his own. Rauschenberg instead focused outward, bringing images of everyday objects into paintings, Combines, and photographs, and picturing the quotidian on mirrored surfaces such that viewers appear in his altered reality. In these two very different ways, Bob and Bruce are alike, producing art from a shared insistence on “I am” from their “say so.”

« Previous Essay

Four Brodsky and Utkin Etchings and Rauschenberg’s Fresco Contest

Next Essay »

The Oracle in the CARDS: Robert Rauschenberg, Bruce Conner, and Michael McClure