« Previous Essay

Monochromes & Mandalas

Next Essay »

Auditions in the Carnal House: Eroticism and Art

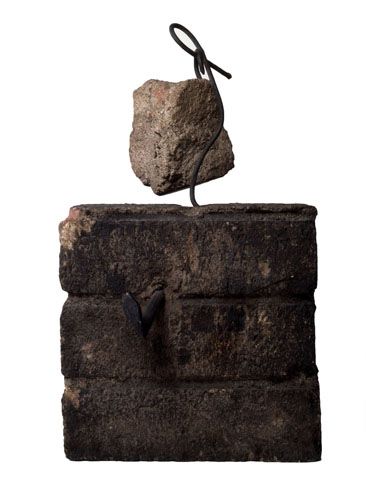

CAT. 64 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), Untitled (Elemental Sculpture), ca. 1953 (detail)

“Rock, Paper, Scissors” is a contest of hand commands, dating from the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) in China. The game has been deployed in various forms throughout history, including as a sport, a metaphor for war, a competitive strategy for selling paintings,1 and a court-ordered resolution to a legal case.2 It has also been played throughout history in various artistic contexts. Summoned as a paradigm for Robert Rauschenberg’s enduring commitment to facture, or making, this essay explores his and other artists’ acute attention to the materiality of art.

Rauschenberg’s appreciation for found objects dates from the beginning of his career and is vivid in his Fettici Personali (Personal Fetishes) (see fig. 2), constructed in Italy in the fall of 1952 and spring of 1953. Regarding his inspiration and selection of the objects that comprise Fettici Personali, Rauschenberg remarked:

The material used for these constructions were chosen for either of two reasons: the richness of their past—like bone, hair, faded cloth and photos, broken fixtures, feathers, sticks, rock, string and rope; or for their vivid abstract reality: like mirrors, bells, watch parts, bugs, fringe, pearls, glass and shells. You develop your own ritual about the objects.3

CAT. 64 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), Untitled (Elemental Sculpture), ca. 1953. Bricks, mortar, steel spike, metal rod, and concrete; 14 1/4 x 8 x 7 3/4 inches (36.2 x 20.3 x 19.7 cm). Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York, New York. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York.

During this period, Rauschenberg also visited the then ill Italian painter Alberto Burri in Rome, bringing with him one of his fetish works as a healing gift. Trained as a physician, Burri served in World War II on the side of the Axis and was captured in 1944 and sent to a prisoner of war camp in Hereford, Texas, until 1946. During his incarceration, Burri began to paint on empty burlap and mail sacks, creating torn, stitched, ragged, and oil-painted works, some of which he exhibited in 1947 in Rome. With surfaces scarred by holes that emphasized the paintings’ brute physicality, the works became metonymies of the wounded bodies that he had sutured and attempted to save during the war. An admirer of Burri’s later series of Sacchi (collage constructions comprised of burlap sacks which he started circa 1949), Rauschenberg expressed his own affinity for the intrinsic character and quality of materials in his work Feticci Personali. Together with Burri’s works, Rauschenberg’s early constructions anticipated the advent of Arte Povera, founded and named by the Italian critic Germano Celant in 1967, a movement in which artists used conventionally non-artistic, or “poor,” materials and emphasized process.

CAT. 74 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), Untitled (Venetian), 1973. Rope, string, and stone; extended: 178 inches (452.1 cm), dimensions variable. Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York, New York. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York.

Upon his return to New York in 1953, Rauschenberg embarked on a series of Elemental Sculptures, nineteen small works combining stone, rusted metal, wood, and other objects that he scavenged from various construction sites around his Fulton Street studio.4 The nine remaining sculptures testify to his poetic interest in, and archaeological appreciation of, mid-twentieth-century Manhattan. Characterized by its brown-gray urban coloring, Untitled (Elemental Sculpture) (CAT. 64), made from bricks, concrete, wood, and disintegrating metal evinces Rauschenberg’s appreciation of an object’s weathered virtue: age, dirt, grime, and rust. “The most interesting things on Fulton Street were the rocks that were dug up every day,” he explained. “So I made a series of rock sculptures.”5 Emphasizing the empirical aspects of the roughly hewn bricks and mortar, from scale and volume to balance and mass, Rauschenberg presented these minimal sculptures without embellishment, paying homage to their austere dignity, a way of working that he described as “re-nourishing something that’s been abandoned.”6

In addition, he encouraged viewers to interact with the work’s components, a facet that would facilitate deeper comprehension of their fundamental proportion, size, weight, materiality, and the cohesion of parts. Twenty years later, he returned to fabricating similar objects, such as Untitled (Venetian) (1973; CAT. 74). Consisting of a rope tethered to the ceiling by a steel hook, Rauschenberg finished the sculpture with a large stone tied to the bottom that anchors the object to the floor. Structuring the interplay of gravitational forces and the swing of the rope, Rauschenberg amplified the essential behavior of the materials, antedating by over a decade artists’ attention to process in the late 1960s.

The San Francisco artist Bruce Conner began making assemblages in the mid-to-late 1950s and, along with Rauschenberg (eight years his senior), was included in William C. Seitz’s groundbreaking exhibition The Art of Assemblage at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City in 1961. Recognized in his twenties as a pivotal American assemblage artist, Conner’s WHEEL COLLAGE (1958; CAT. 8) is an early example of his style before he became more widely known for his use of women’s silk stockings, jewels, and other expressive materials, as well as for the erotic/thanatotic qualities of his early-to-mid-1960s assemblages.

CAT. 8 Bruce Conner (1933–2008), WHEEL COLLAGE, 1958. Assemblage on Masonite (terrycloth fabric, iron wheel, rhinestone studs, paint rag, torn paper, newspaper classifieds), 21 7/8 x 24 x 3 3/4 inches (55.6 x 61 x 9.5 cm). Collection of the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina. Anonymous gift, 2012.7.1. © Conner Family Trust, San Francisco, California / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, New York. Photo by Peter Paul Geoffrion.

A rare and seldom exhibited work, the spare WHEEL COLLAGE is encrusted with weathered torn newsprint that covers its surface. The poetry of the abstract composition resides in the way Conner related its constituent parts. Balancing materiality, process, and concept, he made a subtle and critical connection between the work’s textual and visual elements. Although barely visible, when one examines the texts on the newsprint, some read:

Drills Deep; Drills Heavy; Drills Radial; Boring Machines; Tools; Machinery; Filers; Directory of . . . Assigned a . . . [C]ode Number . . . condition as listed is ______ as statement by ______ . . . publisher assumes no responsibility for ______ Numbered, listed addresses of machinery supply companies (Los Angeles, Santa Fe).

The rusty old wheel in the upper right corner amplifies the references to the material aspects of industrial processes and machinery, as well as to the deep brown and golden tones of the aging newspaper. In the center of the assemblage, Conner placed two paint rags that add color to the work’s nearly monochromatic austerity: one beige and stained with a grey-green paint, the other a moss green towel that he embellished with several rhinestone studs. The paint cloths reinforce the content of the newsprint (or builders’ catalogues) by tying the labor of the artist to that of those who labor.

Just as Conner concentrated on the imbricate relationship between the materials and the theme of the work in WHEEL COLLAGE, Rauschenberg’s San Pantalone (Venetian) (1973; see CAT. 73) features materials that recall the origins of the series in Venice. Barnacle-encrusted tarpaper is combined with wood, metal, rope, and a coconut that extends from a cord to the floor below the relief sculpture. The undulation of the work’s humble tarpaper brings to mind the roll of the sea, while the burned and tortured quality of the materials symbolizes the history of San Pantalone, the martyred saint who, after being repeatedly tortured, was decapitated, a result memorialized by Rauschenberg in the coconut.7 Inspired by his many visits to Venice, the city held special significance for Rauschenberg as the first American artist to win the Grand Prize at the Venice Biennale in 1964. But the Venetian series also pays homage to many aspects of the city from its clergy and churches to its “aqua alta,” or the high water that floods the city in the rainy season.

CAT. 52 Nikolai Panitkov (b. 1952), Stuff Up the Hole, Stuff Up the Crack, 1987. Paint, wood, fabric, and cork; 33 x 33 x 5 inches (83.8 x 83.8 x 12.7 cm). Collection of the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina. Gift of 17 contemporary artists, 1995.16.18. © Nikolai Panitkov. Courtesy the artist and E.K. Art Bureau, Moscow, Russia.

The Russian artist Nikolai Panitkov works with materials in a more conceptual and political way. In Stuff Up the Hole, Stuff Up the Crack (1987; CAT. 52), Panitkov first created a monochrome white painting before punching a hole in its center, which he then plugged with a cork. Next he framed the work and stuffed cotton batting into the cracks around the work’s frame. While this “stuffing” of cracks denotes the materiality and construction of the work, Panitkov’s conception connotes the censorship and silencing of the voices of those who sought to challenge the communist regime during the closing years of the Soviet Union. This painting may also be an index of Panitkov’s participation in the Collective Actions Group in Moscow, a group of conceptual artists whose work focused on events, or “actions,” staged on the outskirts of Moscow, especially in the Izmaylovskow field. Following these events, the Collective Actions Group reconvened at various members’ apartments, especially that of Andrei Monastyrski, the primary theoretician of the group. There, in their intimate surroundings, the group proceeded to discuss the theoretical content of their actions. Panitkov has explained: “We were working on conceptual matters, a worked-out worldview, because dissidence with its social criticism did not interest us very much. Social struggle does not solve existential problems.”8 While the artist conceived of Stuff Up the Hole, Stuff Up the Crack separate from the aims of the Collective Actions Group, the work’s content alludes to the “existential problem” that to exercise free will and determine one’s fate, one must be able to act, action that the stringent Soviet censorship and state control prevented, outside of metaphorical “actions” in a field.

CAT. 53 Lia Perjovschi (b. 1961), Our Withheld Silences, 1989. Strips of paper, textile, printed text, and mixed media; 27 inches diameter (68.6 cm). Collection of the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina. Anonymous gift, 2007.12.3. © Lia Perjovschi. Photo by Peter Paul Geoffrion.

Similarly between 1988 and 1991, the darkest years of the Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu’s censorship, Lia Perjovschi cut up the pages of a French travel guide into tiny strips, creating a series of round books that camouflaged their source. In Our Withheld Silences (1989; CAT. 53), she refers to the state’s confiscation of passports as a means to suppress Romanian citizens’ longing to escape their entrapment. The work also attests to the discrete symbolic forms of communication, or doublespeak, that artists throughout the former Soviet block and within the Soviet Union itself used to render discourse that was threatening to the state impenetrable. Yet her title, Our Withheld Silences, boldly attests to the matter symbolized by the object: self-censorship results from the suppression of individual will.

At the other end of the spectrum is the Ukrainian artist Shimon Okshteyn, a native of Chernivtsi, formerly a city in the Romanian area of Bukovina, which was annexed to the Soviet Union in 1944 by Stalin and is now part of Ukraine. Okshteyn moved to the United States in 1980 and has said that he was strongly influenced by Rauschenberg’s Combines.9 In 1995, he found an armchair on the streets of New York, carried it back to his studio, covered the object in canvas, and then painted it black and white with expressive brush strokes. Next, he painted a technical drawing of the armchair, linking the fabrication of the self-assembled piece of furniture to the chair itself. Finally, he placed Armchair (1995; CAT. 49) at a tilt in front of the painting, uniting a Rauschenberg-like Combine with a Warhol-like diagram into an entirely original, hybrid work of art. “It’s an armchair but not an armchair, because it tilts,” he explains, adding, “Armchair was very conceptual, as any object that the artist touches becomes something else.”10

CAT. 49 Shimon Okshteyn (b. 1951), Armchair, 1995. Mixed media, 92 x 73 5/8 x 42 inches overall (233.7 x 187 x 106.7 cm). Collection of the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina. Gift of Michael K. Chin, 1997.18.1. © Shimon Okshteyn.

The found object that Okshteyn admires in Rauschenberg’s oeuvre is epitomized by Rauschenberg’s Cardboard series. Begun in 1970 in his New York studio and continued after his permanent move to Captiva Island, Florida, in the late fall of that year, Rauschenberg completed the series in 1971.11 In working with the cardboard boxes, Rauschenberg exercised austerity and truth to the materials, and resisted embellishing their surfaces. At the same time, he also manipulated the boxes as material by tearing, bending, and flattening, but also leaving them stained and dented as he found them. “I was trying to wean myself off urban imagery,” he said. “I was in a different environment. Cardboard boxes are everywhere.”12 As Susan Davidson points out, the titles of the Cardboards are as “found” on the boxes themselves.13 The title of Olympic / Lady Borden (Cardboard) (1971; CAT. 72), for example, refers especially to the brand name of an ice cream company that is printed, along with numbers and shipping information, on the surface of the boxes. Enlivened by the marks of use, the boxes affirm their previous lives and stories, which Rauschenberg identified as, “A silent discussion of their history exposed by their new shapes.”14 He also explained: “A desire built up in me to work in a material of waste and softness. Something yielding with its only message a collection of lines imprinted like a friendly joke.”15

CAT. 72 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), Olympic / Lady Borden (Cardboard), 1971. Cardboard, 78 x 47 x 12 inches (198.1 x 119.4 x 30.5 cm). Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York, New York. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York.

Rescuing and reconditioning discarded materials is emblematic of Rauschenberg’s dialogue with the history of the found object, from Cubism to Dada and Surrealism. In addition, when Cardboards are viewed within the context of Pop Art, such as Andy Warhol’s Brillo Boxes (1964), they pose a counterpoint to the celebration of the market and, in Rauschenberg’s words, the “pervasive . . . commodity condition,” about which he asked, “Can one not look into the thing’s residual use value? For what happens to commodity when it leaves the supermarket shelf?”16 Separating himself from Pop, Rauschenberg aligned himself with the ecological movement in his consideration of disposability and the materialism of modern life. Indeed, the environmental movement dates its inception to the first Earth Day, April 22, 1970, an event that nearly coincided with Rauschenberg’s work on the Cardboards, and for which he created the poster Earth Day “to benefit the American Environment Foundation [in] Washington, D.C.”17

While the Cardboards marked an important new direction in his work, the precedent for his use of cardboards must be remembered in his own oeuvre, for Rauschenberg used the paperboard inserts from laundered shirts in Italy during the years 1952 and 1953 to create works like Untitled (Optical Device) (1952) nearly twenty years earlier.18 These paperboards provide the support for drawings, collage, and the application of inexpensive prints culled from Rome flea markets. Untitled (Optical Device) features an intricate engraving featuring an old-fashioned optical device that mirrors a portrait of a woman, who appears on the far right side of the work upside down. The engraving appears with pink tissue paper around it and is framed by strips of graph paper Rauschenberg cut and glued around it. While this work differs in every way from Cardboards, still the paperboard support may be seen as their antecedent. The mixed-media assemblage is striking for its miniature size and portability, subtle and elegant composition, and Rauschenberg’s use of simple materials that evoke a wide variety of associations and recall his interest in the collages and boxes of the American artist Joseph Cornell.

CAT. 75 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), Page 2 (Pages), 1974. Molded handmade paper, 22 inches diameter (55.9 cm). Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York, New York. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York.

Rauschenberg made a prodigious attempt to dignify humble materials, perhaps most eloquently expressed in his Pages and Fuses series, the result of a four-day visit in 1973 to the fourteenth-century paper mill Moulin à Papier Richard de Bas in Ambert, France. There, in collaboration with the mill’s director, Marius Peraudeau, he realized twelve works that constitute the concurrent Pages and Fuses series, including the intricate and minimal Page 2 (Pages) (1974; CAT. 75), ennobling even the most modest of materials: paper. Working with plain paper pulp to which he added twine and rags, Rauschenberg enhanced the texture of the paper while sculpting one of the most ancient images in human history: the circle. The work’s circle also contains a hole in the center recalling the Zen Buddhist ensō, the form that symbolizes the universe and enlightenment, as well as mu, or the void. While being a consummate work in paper, the complexity of this otherwise simple object, as just noted, includes its implied references to Eastern philosophy. For this reason, Page 2 accords with Bruce Conner’s many mandala drawings, and is displayed in the room of this exhibition entitled “Bruce Conner One Man Show (with Rauschenberg).”

The period during which Rauschenberg worked on Pages and Fuses was brief, yet productive, and led to other collaborations with local artisans abroad, and eventually to the prodigious collaborative efforts of the Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange (ROCI) (1984–91). His global view and commitments led the renowned museum director Walter Hopps to describe the ethos of Rauschenberg as one representative of “universal consciousness.”19

Rauschenberg sustained a form of democratic attention to materiality, process, and facture that drew on his modernist antecedents. Although he altered their often-combative political positions, in his Studies for Currents (see CAT. 68–71) and the resulting monumental Currents (1970), he faced the world of radical and frequently disturbing and violent cultural, social, and political change decidedly, yet with the simple means of newspapers and scissors in order to place before the public a testimony to his times. Rauschenberg’s embrace of simplicity, directness, and his abiding belief in the world continues to draw the admiration not only of the public but also of other artists for how he ratified the exploration of every aspect and every material from everyday life. In this manner, Rauschenberg encouraged a visual conversation, symbolically represented in “Rock Paper Scissors“ that weaves through many generations and artists’ oeuvres.20 In his words:

All material has its own history built into it. There’s no such thing as “better“ material. The strongest thing about my work, if I may say this, is the fact that I chose to ennoble the ordinary.21

« Previous Essay

Monochromes & Mandalas

Next Essay »

Auditions in the Carnal House: Eroticism and Art