Next Essay »

Monochromes & Mandalas

CAT. 78 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), The Ancient Incident (Kabal American Zephyr), 1981 (detail)

During an interview with Robert Rauschenberg and his dealer Leo Castelli in 1977, the writer and impresario Barbaralee Diamonstein read aloud Rauschenberg’s famous 1959 statement from the Museum of Modern Art’s exhibition catalogue for Sixteen Americans: “Painting relates to both art and life. Neither can be made. (I try to act in that gap between the two.)”1 Diamonstein’s slow, dramatic reading perhaps reflected her respect for the definitive role that the twenty-one-word statement had on art and its histories. By 1977, Rauschenberg’s “act in the gap” had become a maxim for experimental art, from assemblage, happenings, Fluxus, body and process art to art and technology in the 1960s, and from performance and installation to pluralism in the 1970s. Rauschenberg’s appropriated imagery, combined with photography and painting, would soon also be recognized as the antecedent for visual aspects of postmodernism, especially neo-expressionist painting in the 1980s;2 and his worldwide travels and insistence on collaboration and interactivity would inform “relational aesthetics” in the 1990s and collectivity in the 2000s.3 But, following her recitation, Diamonstein just looked at him.

Rauschenberg picked up the conversation in his careful manner, speaking with determined forethought:

I don’t think that any honest artist sets out to make art. You love art. You live art. You are art. You do art. But you’re just doing something. You’re doing what no one can stop you from doing. And so, it doesn’t have to be art. And that is your life. But you also can’t make life. And so there’s something in between there that, because you, you flirt with the idea of that, that it is art.4

Diamonstein interrupted him to ask “Are you saying that art, painting, rests more in ideas than the painting itself?” Rauschenberg answered, “No.” Then continued:

I think the definition of art would have to be more simple-minded than that, and it’s about how much use you can make of it. Because if you try to separate the two, art can be very self-conscious and a blinding fact. But life doesn’t really need it. So it’s also another blinding fact.5

After his introspective analysis, full of many thoughtful pauses, Rauschenberg stopped talking. Diamonstein avoided, or did not grasp, the sweeping implications of his arresting commentary and, failing to explore its philosophical depth, ironically followed up with a question about his approach to “surface.”

Diamonstein was not the only critic, just the first, to miss the broader implications of Rauschenberg’s thought. Curiously, it appears that no scholar has remarked on his 1977 comments. Despite omission in the abundant literature on the artist, Rauschenberg’s 1977 amplification of his 1959 statement provides his most expansive explanation of his process in the interstice where he “just” did “something” that “no one could stop [him] from doing.” His 1977 commentary is also Rauschenberg’s most incisive remark on artistic integrity in the act of making,6 the clearest identification of his emotional states in the gap, and the most commanding example of his conviction that the significance of art resides in its “use” value. This essay explores these lines in Rauschenberg’s thought, attending closely to the meaning implied by his process in the gap, the site of his sense of immediacy between the incommensurability of one blinding fact (art) and another (life).

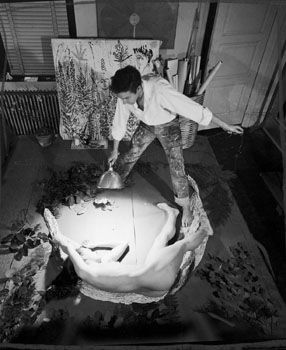

In 1949, a full decade before he articulated the gap as the space within which he did “something,” the artist Susan Weil introduced Rauschenberg to creating monoprints on blueprint paper.7 By exposing the paper to the ultraviolet light of a sunlamp, it turned a rich ultramarine blue, leaving the covered areas of underexposed paper in varied tones of pale blue to white. Using this paper, Rauschenberg made striking blueprint images of his friend Patricia Pearman, who posed nude in various positions, one picture of which LIFE Magazine published in its April 9, 1951 issue, along with images of Rauschenberg and Weil making other types of blueprint images (fig. 1).8

fig. 1 Robert Rauschenberg creating artwork using a nude model on blueprint paper with a sun lamp, New York, NY, 1951. The LIFE Picture Collection. © Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images. Photo by Wallace Kirkland.

The famous photographs that Hans Namuth took in 1950 of Jackson Pollock standing over and on his canvas while painting on the floor appeared for the first time a month later in Portfolio magazine, as well as in the May 1951 issue of Art News. Harold Rosenberg’s theory of action painting followed in the December 1952 issue of Art News.9 That same year, Georges Mathieu began having himself photographed while painting and would soon begin to perform action paintings publically. In October 1955, the Gutai artist Kazuo Shiraga would perform Challenging Mud in Osaka, Japan, wrestling on the ground with viscous pigment mixed with mud; and, on June 5, 1958, Yves Klein would begin experiments using a female nude model who immersed herself in his patented International Klein Blue paint, printing her body on canvas placed on the floor of his friend Robert Godet’s Paris apartment.10 As LIFE was distributed worldwide, it is certain that Mathieu knew the image of Rauschenberg working with the nude model, and it is highly possible — even probable — that Klein and Shiraga also saw the images at some point. In this regard, a historical relationship exists between Rauschenberg’s concept of using a live nude to create images and artworks that followed throughout the world.

Yet, by describing his artistic process in 1959 as an effort to “act” in the gap, it may appear that Rauschenberg aligned his approach with the history and theory of action painting associated with the events just cited.11 But while especially admiring of Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline, Rauschenberg rejected the notion of art and life collapsed into an undifferentiated unity and, instead, marked out a place that distinguished, even as it imperceptibly interconnected, the two. In the 1949 blueprint works, Rauschenberg remained the maker, not the work itself, even as he posed in several of the monoprints.12 His conceptually nuanced position vis-à-vis the fusion of art and life would earn Rauschenberg the sharp criticism of John Cage. “I think there’s a slight difference between Rauschenberg and me,” Cage explained in 1968, adding, “And we’ve become less friendly, although we’re still friendly. We don’t see each other as much as we did.”13 Cage explained the breach this way: “I have the desire to just erase the difference between art and life, whereas Rauschenberg made that famous statement about working in the gap between the two. Which is a little Roman Catholic, from my point of view.”14 When the interviewer, Martin Duberman, an authority on Black Mountain College, asked Cage what he meant by this last comment, Cage responded, “Well, he makes a mystery out of being an artist.”15

Cage’s comments reflect his own unease with how Rauschenberg had, in only a few words, unsettled the idea of either the unity or the dualism of art and life, fundamentally exposing the claim for unity as utopian, and for dualism as falsely oppositional and potentially hierarchical.16 Instead, Rauschenberg would “try,” as he wrote, to establish his own position, one of presence between the blinding facticity of art and life.17 “I am in the present,” Rauschenberg stated in a 1961 interview, “with all my limitations but by using all my resources.”18 In Autobiography (1968; see CAT. 66), his over sixteen-feet-tall, three-panel lithograph, Rauschenberg ends the spiral text in the middle panel, which also resembles a thumbprint, by stating that he is “creating a responsible man working in the present.”19 Read in this context, the blueprint works anticipated Rauschenberg’s identification of the gap, which both constituted the site of presence and provided the resource of an open space where he was neither completely in art nor in life. As for Cage’s characterization of Rauschenberg’s thought as “Roman Catholic” and his mendacious charge that Rauschenberg “mystified being an artist,” Cage knew better that both were untrue, shades of which I explore in more detail below.

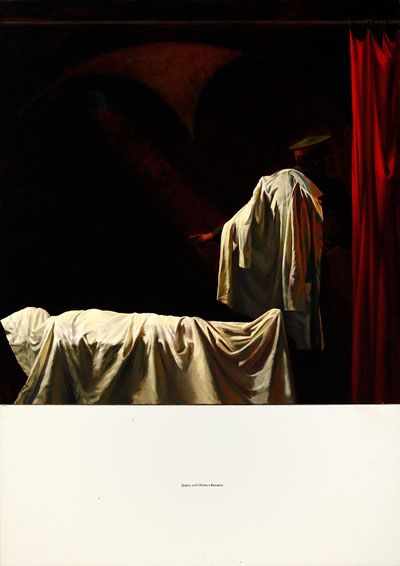

CAT. 40 Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid (b. 1943 and b. 1945), Stalin with Hitler’s Remains from the series Anarchistic Synthesism, 1985–86. Oil on canvas, 84 1/4 x 60 1/4 inches (214 x 153 cm). Collection of the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina. Museum purchase, 1992.8.1. © Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid. Courtesy Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York, New York. Photo by Peter Paul Geoffrion.

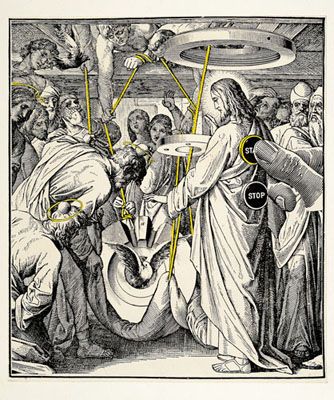

Taking the model of Rauschenberg’s art and practice, Rauschenberg: Collecting & Connecting presents his work in interrelation to a range of international artists’ as interlocutors. Staging eight thematic rooms, the exhibition emphasizes visual conversations and connections among the artworks rather than comparisons of likeness and difference. Each room brings together works from Rauschenberg’s own collection of his art with works from the collection of the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University. These surprising combinations offer new perspectives on a heretofore tacit dialogue between Rauschenberg and the Nasher Museum’s significant, but little known, corpus of Soviet nonconformist artists of the 1980s and 1990s, and its newly acquired collection of Bruce Conner’s art. The Soviet collection includes such works as Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid’s monumental Stalin with Hitler’s Remains (1985–86; CAT. 40), with its white monochrome panel hinged to the bottom; and the Bruce Conner collection includes DEUS EX MACHINA, the only hand-colored print from Conner’s CHRIST series of 1987 (CAT. 34). The eight rooms cluster around the following themes: Black and White (with Red): Variations on the Monochrome; North Carolina and Italy: Rauschenberg’s Photographs 1949–52; Rock Paper Scissors: Materiality, Process, Society; Light, Mirror, and Mirage: Capturing Ephemeral Nature; Auditions in the Carnal House: Picturing Eroticism; Soviet/American Array: Part I, Politics and Friendships; Soviet/American Array: Part II, Cacophony of Cultures; Bruce Conner One Man Show (with Rauschenberg): A Visual Dialogue.

CAT. 34 Bruce Conner (1933–2008), DEUS EX MACHINA from the CHRIST SERIES, 1987. Print with hand coloring on paper, mounted on board; 6 7/8 x 6 inches (17.5 x 15.2 cm). Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina. Promised gift of anonymous donor, L.13.2012.40. © Conner Family Trust, San Francisco, California / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, New York. Photo by Peter Paul Geoffrion.

The icon for these visual exchanges is Rauschenberg’s conceptually epic sculpture The Ancient Incident (1981; CAT. 78). Supported by two identical sets of rough, wooden stair-steps with metal fittings, twin wooden chairs hover seven feet above the floor, seats facing each other and just touching across a space at the summit. Precariously balanced, the interface between the chairs is an analog for the unrestricted opening that Rauschenberg sought for doing and being in the “gap” that is unmediated by the more calcified categories of “art” and “life.” The conversation suggested by the prodigious structure of The Ancient Incident equally serves as a model for parallel sites of multidimensional discussions about connecting two collections. These discussions invite viewers to consider each work as a discrete entity and as part of overlapping, intersecting, and diverse set of relations with other artworks, materials, approaches, and subjects. Such unrestricted visual dialogues reintroduce the “use” value, upon which Rauschenberg insisted, and cultivate what he cherished most: the act of looking long and thinking hard in order to bring fresh vision to art.

A prolific and curious artist, who altered the history of world art, Rauschenberg advocated for peace, cooperation among nations and peoples, and protection of the environment and animals. Travelling throughout the world for over thirty years, Rauschenberg commented in a 1984 statement at the United Nations:

I feel strong in my beliefs . . . that a one-to-one contact through art contains potent peaceful powers and is the most non-elitist way to share exotic and common information, seducing us into creative mutual understandings for the benefit of all. Art is educating, provocative, and enlightening even when first not understood. The very creative confusion stimulates curiosity and growth, leading to trust and tolerance. . . . It was not until I realized that it is the celebration of the differences between things that I became an artist who could see.20

CAT. 78 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), The Ancient Incident (Kabal American Zephyr), 1981. Wood-and-metal stands and wood chairs, 86 1/2 x 92 x 20 inches (219.7 x 233.7 x 50.8 cm). Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York, New York. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York.

Rauschenberg expressed an abiding personal judgment that ethical principles prevail in making “something” when, in his initial retort to Diamonstein’s reading of his 1959 statement, he said: “I don’t think that any honest artist sets out to make art.” His first and next fourteen sentences on the topic deserve closer attention. The following interpretation seeks to contribute to a better appreciation of the stakes for Rauschenberg when he positioned the “act” of making something in the gap, as well as to the meaning of his art in general.

The historical context for his insistence on artistic integrity, the honesty of the artist, is worth considering here. Rauschenberg entered the art world during the height of what he called the abstract expressionists’ “self-confession and self-confusion,” a mode of existence he rejected for himself.21 He was instrumental in bringing about the shift from what he understood to be egocentrism to the ambiguous social commentary of pop art, from whose equivocal cultural positions he also removed himself. He was internationally renowned by the late 1970s when postmodernist irony arrived as the cultural iteration of poststructuralist questioning of inherited beliefs and structures of knowledge. But while Rauschenberg would remain distant from the extremes of postmodernist radical relativity, his art modeled aesthetic paradigms for radical visual relativity and respect for difference.

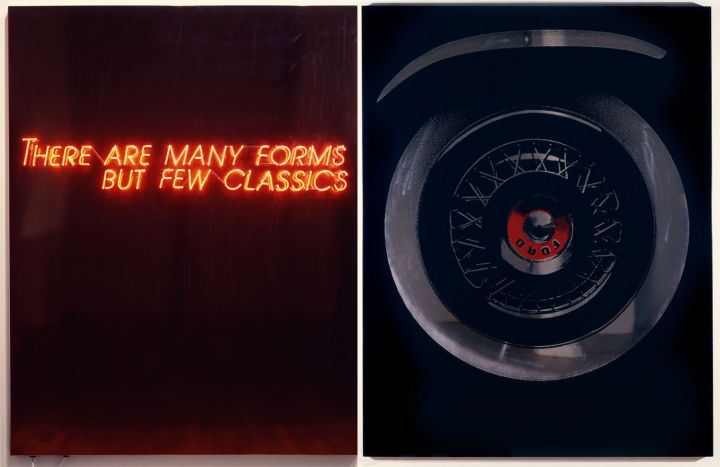

Among the many works in Rauschenberg: Collecting & Connecting that exhibit traits associated with postmodernism are Solar Elephant (1982; see CAT. 82), or what Rauschenberg called a “free-standing picture” (another term he used for Combine), with its juxtapositions of technical drawings, organic forms, and objects from popular culture; and his four-paneled, ceramic version of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa (1503–17), the feverish Pneumonia Lisa (1982; see CAT. 81) that Rauschenberg superimposed with a variety of images, from a horse and the face of Venus in Sandro Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus (ca. 1486) to a motorcycle fender decorated with a Mickey Mouse decal.22 These works evince the narrative instability characteristic of postmodernism, as well as what Sam Hunter described as Rauschenberg’s “mercurial consciousness.”23 Rauschenberg would put it this way in 1963: “My fascination with images . . . is based on the complex interlocking of disparate visual facts . . . that have no respect for grammar.”24 Five years later, he would observe: “Now we have so much information. A painter a hundred or two hundred years ago knew very little. . . . It wasn’t natural for him also to take into consideration cave painting and fold it into his own sense of the present.”25

Despite Rauschenberg’s proto-postmodern consciousness of the random function of images in contemporary society, his unrestrained appropriation of images, and his careful juxtaposition of seemingly unrelated images, some observers might view his steadfast insistence on “honesty” as old-fashioned, particularly in cultural circumstances favoring irony. This would be true especially for those who claim that they no longer know “what art is,”26 no longer “believe in” the values once attributed to art,27 or find such principles laughable in the context of the soaring global market for art, which transmogrifies the Nietzschean “transvaluation of values” into its obverse: rather than exalt life and creativity, the market reduces everything to capital.

“[O]nce irony is admitted,” conceptual artist Michael Asher noted in 2009, “nothing can be innocent.”28 Rauschenberg was anything but innocent. Yet while he deployed paradox in his work, he did not share the pervasive cynicism of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, as a letter he wrote in 1999 regarding The Happy Apocalypse (see fig. 19), a project he undertook for the Vatican, makes clear. Firmly declaring the purpose of his art, Rauschenberg wrote: “Healing with faith is paramount. My art work is filled with hope, courage, and strength; it will work to support inspiration and life.”29 Asher did not refer to Rauschenberg when he wrote the following, but he may as well have been describing Rauschenberg’s stance as an alternative to the insouciance of our era:

It takes a strong act of will to reassert that a certain phenomenon—a painting, a gesture, a dumb object—is just what it purports to be. . . . Once one reinvests art with some consideration to the real, this yawning from one extreme to the other [high vs. low and art vs. life] has to cease. The specific relationship between work and viewer reasserts its importance, as the body becomes the site of a different kind of interplay between the visceral and intellectual aspects of the experience.30

Rauschenberg demonstrated strong acts of will at an early age. As “a shy child [who] often hid from people,”31 he survived his father’s “physically violent, abusive, and alcoholic” behavior;32 and, as an adult, endured “his father’s dying words: ‘I never did like you, you son of a bitch.’”33 Biographers seldom reveal these unsavory details of his life, or the fact that when Rauschenberg returned home from military service in World War II, his family had moved to another town without telling him or leaving a forwarding address. Usually Rauschenberg’s decision to change his first name from Milton to Bob is attributed only to the moment he determined to become an artist and entered the Kansas City Art Institute in 1947, rather than to the fact that he bore his father’s name, an identity he shed in order to leave his past behind. Yet, to the question, “How much of your work is autobiographical?” Rauschenberg replied: “Probably all.”34

What is often repeated about his biography is that during his teenage years, Rauschenberg began rejecting the religious dogmas of his Texas fundamentalist Christian community and the Church of Christ, especially taboos against dancing. But one anecdote — which underscores his loneliness — is not often told. Rauschenberg explained that when he was just fifteen, in response to a preacher insisting that the Bible advocated marrying a virgin rather than a widow, he “stood up in church,” he remembered, “and flung my arms out and said, ‘Why? You can’t help but sometimes be a widow!’”35 Forty-seven years later he was still upset by the idea and remarked to Barbara Rose: “How could God say something like that? People get lonely.”36 They do, and he did, often referring to the “loneliness of painting,” which, in part, accounted for his devotion to collaboration in art and technology, and his decades-long participation in dance and theater.

In college, after refusing to kill and dissect a frog, Rauschenberg was expelled. When he entered the Navy at eighteen and announced that he was not going to kill anyone, he was trained as a neuropsychiatric technician, running three different wards with only one doctor. “No, I was not forced to fight,” he said. “What I witnessed was much worse. I got to see, every day, what war did to the young men who barely survived it. . . . Every day your heart was torn until you couldn’t stand it. And then the next day it was torn up all over again. And you knew that nothing could help. These young boys had been destroyed.”37 Rauschenberg also compared his psychological state at the time to those of his patients: “If an analyst had written mine down, I would have been right on top.”38 To these experiences add his self-doubt, rooted in severe dyslexia, his bisexuality, voracious appetites, and his alcoholism.

Then consider his many accomplishments and high international profile in the media, from newspapers and popular magazines to art journals and television. His prominence makes it easy to understand that Rauschenberg’s strong will could cause friction and even provoke jealousy.39 After all, as one of his high school teachers said, Rauschenberg was “a DEFINITE leader. . . . He always had ideas: Milton always had some solution to suggest.”40 Ileana Sonnabend described him as a “strange mixture of boastfulness and humility, depression and high spirits,” and she especially noted “a spiritual quality in his works, as well as a poetic and ephemeral quality.” Finally she observed an aspect of his personality that unsettled some: “People like to hold on to what they know. Bob likes to shake them out of their habits.”41

I recount these and other biographical factors for how they inform about Rauschenberg’s concept of “honesty,” which comprised his determination to be truthful to himself as a maker of “something,” forthright in his devotion to the object in all its material complexity, committed to engagement with everyday realities, and dedicated to the interplay between the visceral and intellectual aspects of viewers’ experiences. Rauschenberg best expressed this honesty when he commented in 1963:

My morality is not to walk in my own footsteps.42

What he meant by this poetic statement was that, while “all” of his work was to some degree autobiographical, the integrity of his art depended upon bringing the viewer into the work.

Thinking of not walking in his own footsteps, Rauschenberg incorporated his classmates into his work in 1949 while a student at the Art Students League in New York by putting canvas on the floor at the entrance and recording everyone’s footprints as they entered the room. Two years later, he painted his series of modular White Paintings (see CAT. 58), which Walter Hopps observed were “of acute importance” to Rauschenberg for how they “became palpable objects subject to ambient light and shadows.”43 What the White Paintings pictured for Rauschenberg was the presence of anyone and anything in the room, shadows that captured a quixotic and ephemeral history of everything that had once been there. What is also fascinating about the White Paintings is that under certain light conditions, one can see one’s own shadow, as well as a faint double of it. This is possible when viewing the seven-panel White Painting in Rauschenberg: Collecting & Connecting.

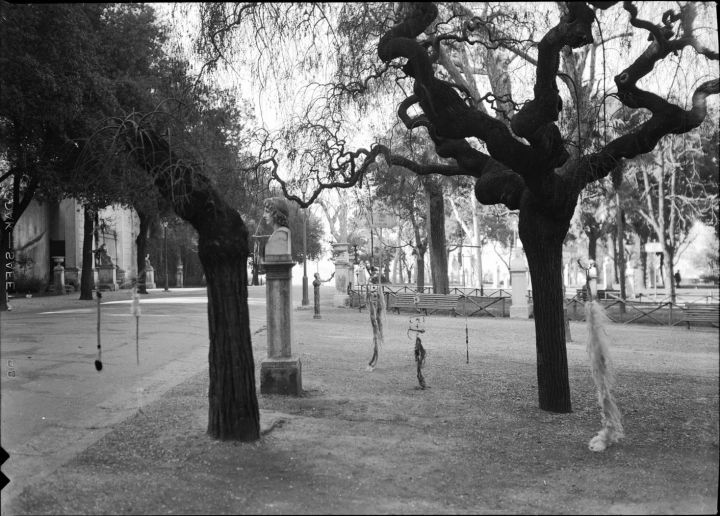

fig. 2 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), Untitled [nine Feticci Personali, Rome], 1953. Gelatin silver print, 13 x 15 inches (33 x 38.1 cm). © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York.

In 1952–53, during what he called his “nine-month trip to the Mediterranean and into North Africa,” Rauschenberg made boxes and “Constructions,” exhibiting them at the Galleria dell’Obelisco, which titled the works Scatole Personali (Personal Boxes) and Feticci Personali (Personal Fetishes) (fig. 2). In his exhibition statement, Rauschenberg wrote that he had chosen the materials for the “Constructions” for “the richness of their past . . . or for their vivid abstract reality,” and he suggested how to interpret and use both the boxes and constructions:

In other [boxes] one or several compartments are left empty for you to add bits of your own choice, to rearrange the contents, or to leave them in their emptiness which signifies unknown possibilities. . . . A hanging construction of mirrors to mirrors is visual infinity. Other stringlike totems hang pretentiously boasting of their fictitious past. A contemplative instrument is made with a bead on a coil of wire. You may develop your own ritual about the objects. The order and logic of the arrangements are the direct creation of the viewer assisted by the costumed provocativeness and literal sensuality of the objects.44

To photograph the Feticci Personali in 1953, Rauschenberg suspended his works from trees and statuary in a park, a temporary installation that anticipated the Japanese Gutai’s eccentric structures and first outdoor exhibition in 1955. The Feticci Personali also suggest the “poor,” or non-aesthetic, materials and modes of presentation that interested artists associated with the Italian art movement Arte Povera, founded in 1967.

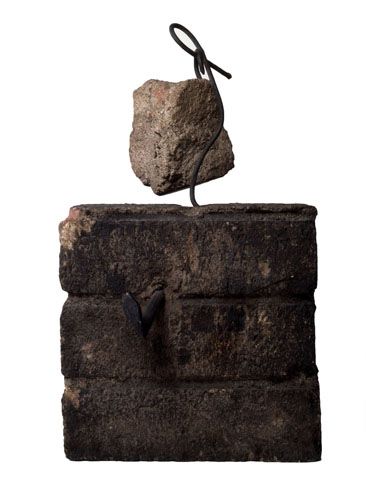

CAT. 64 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), Untitled (Elemental Sculpture), ca. 1953. Bricks, mortar, steel spike, metal rod, and concrete; 14 1/4 x 8 x 7 3/4 inches (36.2 x 20.3 x 19.7 cm). Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York, New York. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York.

Scatole Personali and Feticci Personali were also foundational for Rauschenberg’s own series of Elemental Sculptures, made in 1953 after returning from Italy to New York. Some of these works are uncompromisingly minimal in structure and brute in materials, like Untitled (Elemental Sculpture) (CAT. 64) with its bricks, mortar, steel spike, metal rod, and concrete. But others in the series are more yielding and interactive, consisting of found blocks of wood and rounded stones often tethered together with twine. Rauschenberg encouraged the public to manipulate the component parts of such works, and a photograph of him sitting irreverently, but with a solemn expression, on one of the Elemental Sculptures suggests the interaction with these works that he sought from the public. He exhibited the sculptures together with a black monochrome, a matte-black monochrome, and two White Paintings in a two-person show with Cy Twombly at the Stable Gallery in New York in September of 1953.

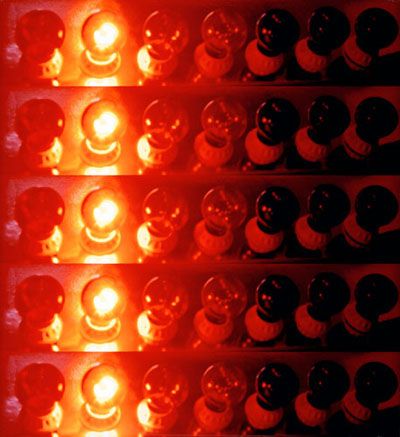

Whereas the Elemental Sculptures ask for actual physical involvement, all of Rauschenberg’s art requires a highly active visual engagement with his superimposed and transposed images, words, and signs. But his most aggressive, inescapable technique for including viewers in his work was his extensive use of mirrors and/or reflective surfaces: works like the Carnal Clock series (1969; see CAT. 67), which included mirrored Plexiglas, and Wild Strawberry Eclipse (Urban Bourbon) (1988; see CAT. 86), which, like many of his painting series of the 1980s and 1990s, featured enameled and mirrored aluminum surfaces.

Considered together, these three means of enticing or capturing viewers — cast shadows on paintings, actual manipulation of objects, and mirroring or reflecting in sculptures or paintings — relate to what seems to have been three primary objectives for Rauschenberg: to offer the possibility to viewers for an exchange of fields of vision; to activate viewers by bringing their presence into the work; and to emphasize the present, whereby one literally enters into the charged space Rauschenberg himself inhabited, the gap to which the public literally contributes through the presence of viewers in the works, bodily reminders that reinvigorate the immediacy and constantly changing imagery in his art. As he said in 1960: “Immediacy, the only thing you can trust.”45 Once bodily engaged in the operation of a sculpture, or virtually embodied within the mirrored surface of a painting or sculpture, viewers have no choice but to be “honest,” in the sense that in the now of the present any act or image is what it is: one cannot hide from, or alter, one’s reflection or shadow or action. In these ways, Rauschenberg’s concept of the gap existed apart from, while enveloped in, art and life, an interstice like that between water and air.

Many of these elements come together in Litercy (Phantom) (1991; CAT. 87). Like so many of his works, Litercy feels monumental but is human-sized, modest, like Rauschenberg himself. A silvered monochrome, resembling grisaille, Litercy includes photographs and silvered pigments that Rauschenberg transferred onto its mirrored aluminum. The work brings viewers into direct contact and interaction with images, signs, and texts, more than most of Rauschenberg’s works on reflective surfaces, and it is for these, and many other, reasons that I explore this work in depth, proposing that it is the quintessence of Rauschenberg’s relation to the gap and how he brought the world into that fissure in reality that is art.

CAT. 87 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), Litercy (Phantom), 1991. Pigmented varnish on mirrored aluminum, 49 1/2 x 85 inches (125.7 x 215.9 cm). Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York, New York. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York.

A brief introduction to Litercy, from left to right, will help. On the left, a man paints the word Wate[r]; ghostly shadows of trees appear in the middle ground; and on the right, a building strewn with pennants also sports a sign that reads “Bob’s”, as well as the word “Hand”, and a sign painted on the side of a building of a hand with its index finger pointing. The latter doubles the concept of hand while visually reinforcing the word and creating continuity and difference through word and image. This is just the first of many doublings in the work. Standing and moving before the painting, one sees oneself reflected near, or on top of, the figure, words, and images. A riveting overlap occurs when the viewer comes into contact with the words Bob’s Hand, which then forms a textual allusion to the artist and the appendage responsible for the work’s making.46 Accordingly, as we become part of the image and make contact with the words in Litercy, we enter a sea of sign painters: first, in the literal figure of the man painting the sign; second, in the metaphorical figure of Rauschenberg, the maker of signs; and, third, in the form of one’s own reflection as it joins the sign makers who create and comprise the content of the painting. Seen in the space with the hand of the maker, the viewer’s action is doubled, becoming simultaneously the object of one’s own gaze and that of the gaze of other viewers as well a creator of the picture.

The symbol of the pointing finger continues the multiplication of signifiers, as its gesture summons one both into the space where the painting lives, and out beyond its parameters. While reflected in the painting, a viewer may reach out virtually to touch the pointing finger, fingertip-to-fingertip, as if re-enacting God’s finger touching Adam’s finger in Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam (1511–12) on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Yet, this pointing finger is not that of God, but only the deictic sign of a command to look: but not just look and not just look anywhere. Pointing from inside the picture to outside its frame, the finger returns viewers to the space of the museum, to art, and to life. Thus can Bob’s hand be said to touch the viewer and to signal, or indicate, his or her exit from the painting by pointing beyond it. In this way, the pointing finger is an overt directional guide that may be understood to refer to all aspects of Rauschenberg’s concepts in his 1959 statement: art — try to act in the gap — life.

As long as viewers move before Litercy, they continue to act upon its imagery, maintaining its liveliness in the present. But as soon as they depart the space of the painting, Litercy becomes an obdurate object, datum in the territory of the blinding fact of art and the blinding fact of life. Rauschenberg had already identified the facticity of an object in 1958 when he commented upon and described “an Etruscan hand,” which he owned, as “that’s just that. It’s just so literal. It’s a fact. A hand.”47 Rauschenberg’s fascination with this Etruscan hand resurfaces in the reference to three hands in Litercy: the sign painter’s hands; Bob’s hand; and the hand with the pointing finger. Rauschenberg explained that his paintings “are all facts [that] your mind . . . adds up to something.”48 These facts are literally visual or invisible (as the sign painter’s hands), and play off one another to awaken the viewers’ imaginations to the liveliness of the gap in which they are participants in contributing to the life and imagery of the painting. This process is something akin to how Rauschenberg described his practice: “I work very hard to be acted on by as many things as I can. That’s what I call being awake.”49 However intriguing the vitality of Litercy, the painting is much more than a tutorial in Rauschenberg’s effort to “try to act in the gap,” or how he involves viewers in and awakens them to that site.

Litercy is, to my mind, one of the great (overlooked) paintings of the twentieth century, an assertion that becomes clearer when the painting is placed first in conversation with René Magritte’s The Treachery of Images, more commonly known as Ceci n’est pas une pipe (1928–29), and secondly, when it comes into dialogue with Velazquéz’s Las Meninas (1656). Beginning with Magritte, as in The Treachery of Images, so in Litercy. Neither the images nor the words represented are what they appear to be. The painted representation of a pipe is not a pipe; the digit pointing is not Bob’s finger; the words “Bob’s” and “Hand” are not Robert Rauschenberg or his hand. Ceci n’est pas un homme ni une main. In addition, the exterior world that appears in Litercy, or, for that matter, in the White Paintings, is not the thing itself. The former is only a mirror reflection, the latter a shadow diffraction that, as I suggested above, even doubles itself under certain lights. Diffraction is the action of light as it bends in passing around an obstruction or through a slit to become an indistinct form. Deploying such operations in painting, Rauschenberg takes Litercy to the depths of the chicanery Magritte identifies in his title The Treachery of Images.

In a 1966 letter to Michel Foucault regarding the philosopher’s meditations on the relationship between words and things in his book Les Mots et les choses (1966), Magritte concentrated on the difference between the words “resemblance” and “similitude,” as well as on how painting brings viewers into a confrontation with the slippery interrelationship between the visible and invisible.50 “Things do not have resemblances, they do or do not have similitudes.” Magritte announces, and proceeds:

[G]reen peas have between them relations of similitude, at once visible (their color, form, size) and invisible (their nature, taste, weight). It is the same for the false and the real, etc. . . . Only thought resembles. It resembles by being what it sees, hears, or knows: it becomes what the world offers it. It is as completely invisible as pleasure or pain.51

Litercy is a visual symphony of reflected and diffracted similitudes that render viewers present in the painting. Like green peas, we bear similarities (or not) in color, form, and size, while retaining our invisible nature, thoughts, pleasure, and pain. “But,” Magritte cautions, “painting interposes a problem” for the visible and invisible, since,

[T]here is the thought that sees and can be visibly described. Las Meninas is the visible image of Velázquez’s invisible thought. Then is the invisible sometimes visible? On condition that thought be constituted exclusively of visible images.”52

Again, Litercy not only proves, but augments, Magritte’s thesis by further throwing realism into question and unraveling representation through visible paradox and contradiction.

Rauschenberg constitutes thought in two visible ways in Litercy: first from within the work proper, as the painting requires viewers to think through what they see in words (Wate[r], Bob’s, and Hand) and in images (sign painter, shadows of trees, building, sign of a pointing hand), and think these words and images through in relation to Rauschenberg’s actual production of the painting; and, secondly, from without, by bringing viewers and their worlds into the work with all the attendant invisible thoughts and emotions that surface as we see ourselves constituted as signs, and as we act in, and think about, the psychological and conceptual significance of our experiences in that space. Thus does Rauschenberg increase, in manifold ways, the consequences of the concepts in Ceci n’est pas une pipe. No one would “seriously argue that a word is what it represents — that the painting of the pipe is the pipe itself,” as James Harkness observes in his introduction to Foucault’s This Is Not a Pipe. “Yet,” as Harkness adds, “it is exactly from the commonsense vantage that, when asked to identify the painting, we reply, ‘It’s a pipe.’ — words we shall choke on. . . .”53

All this makes perfect sense, until Rauschenberg throws down the gauntlet to both Magritte and Velazquéz. What if what we see in Litercy is what it represents? This is my hand reaching out to touch the pointing finger, and so on. Here the discussion turns to Las Meninas (1656) for how Velazquéz staged the viewer — in view — by painting a representation of a mirror in which two figures, standing outside the picture, look into its scene and become part of the events that the painter himself is still painting. If, following Harkness, we ask: “Is that the king and queen?” The answers might be, “Yes, certainly.” Or, “Perhaps people of the court?” More words to choke on. But what if one asks, “Who is that in Litercy?” We would have to acknowledge that they are we. This is I standing near the sign painter’s scaffolding, and it is also me as a representation, a mirror image that is neither here nor there. This is the territory of heterotopia where, as Foucault notes, things become “disturbing, probably because they secretly undermine language, because they make it impossible to name this and that . . . and are part of the fundamental dimension of the fabula.”54 In these many ways, Rauschenberg’s interests dovetail with Magritte’s fascination with verbal/visual non-sequiturs, with Foucault’s conceptualization of heterotopia, and with Velazquéz’s distortions of space, time, and politics. Such a space for Magritte was the epitome of the surreal. For Foucault, it was the non-hegemonic space of utopia. For Velazquéz it held the enigmas of representation and the illusions of identity. For Rauschenberg, it was the space of now, the intangible crack between artifice and reality, which he insisted throughout his career we must inhabit with him, even if only momentarily.

Rauschenberg’s title, Litercy, could equally be said to entertain Magritte’s terrain of revelation and concealment, insofar as it could be seen as a trope of the visible and invisible. We might assume that Rauschenberg’s initial misspelling of the word “literacy” was an unintentional dyslexic mistake, a spelling error that he eventually intentionally decided to retain. Suggesting this order of intentionality is not just guesswork: Rauschenberg was fanatical about using the dictionary to correct his many spelling errors.55 Thus in maintaining the misspelt title, Rauschenberg pointed (like the pointing finger in Litercy) to the fact that literacy, or the assumption of education, competence, and knowledge, may reveal nothing of the invisibility of education, competence, and knowledge. In other words, good spelling can hide ignorance, just as bad spelling may have nothing to do with intelligence.56 Litercy could also be seen as pointing its finger at the visually illiterate just as the finger was pointed to Rauschenberg for not being textually literate. Apropos of Magritte’s words “painting interposes a problem,” Litercy hangs as visible evidence of otherwise invisible thought.

Magritte’s point is further borne out in Rauschenberg’s non-singular act of elision: The deletion of the “a” from the title echoes the absence of the letter “r” in the sign painter’s “Wate[r].”57 Viewers and readers fill in what is missing with their experience, or as Magritte adds, a painted image is “intangible by its very nature” and thus “hides nothing, while the tangibly visible object hides another visible thing — if we trust our experience.” He then reminds us that while the invisible “hides nothing . . . the visible can be hidden.”58 Magritte is simultaneously talking about the arbitrary condition of signs, what can be immediately known, and what may be discovered in the interrelationship of thought, trust, and experience.

CAT. 74 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), Untitled (Venetian), 1973. Rope, string, and stone; extended: 178 inches (452.1 cm), dimensions variable. Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York, New York. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York.

For Rauschenberg, experience was everything: “I put my trust in the materials that confront me, because they put me in touch with the unknown.” Only then does he “begin to work,” and only “when I don’t have the comfort of sureness and certainty.” But how does he arrive at such a mental condition? He answers:

Sometimes Jack Daniels helps too. Another good trick is fatigue. I like to start working when it’s almost too late . . . when nothing else helps . . . when my sense of efficiency is exhausted. It is then that I find myself in another state, quite outside myself, and . . . things just start flowing and you have no idea of the source.59

In other words, to become fully conscious Rauschenberg lost himself in any number of techniques, from inebriation and exhaustion to the prudent abandonment of the arrogance of self “efficiency” and “sureness and certainty.” He claimed that by becoming “quite outside” himself he could open his consciousness to the “unknown.”

Care must be taken here, however, as Rauschenberg exaggerates. The fact remains that his “trust in materials” anchored him to the facticity of things, and that facture tethered him to reality, not unlike how the rocks and other objects he fastened to his paintings, sculptures, and Combines secured the work to the world around them. These objects might be considered metaphors for Rauschenberg’s effort to reach out of the gap and into the world through his work, ultimately securing it (and himself), however blinding, to art and to life. Untitled (Venetian) (1973; CAT. 74) and San Pantalone (Venetian) (1973; CAT. 73) are two such works in this exhibition.With a rock in the former and a coconut in the latter, Rauschenberg met reality.

CAT. 73 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), San Pantalone (Venetian), 1973. Barnacle-encrusted tar paper, wood, metal, rope, and coconut; 70 x 92 x 8 inches (177.8 x 233.7 x 20.3 cm). Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York, New York. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York.

Perhaps the most subversive tactic that Rauschenberg marshaled in Litercy was the visualization of the phenomenon of similitude in the relationship between the painting’s reflective surface and the sign-painter’s unfinished word: “Wate[r].” Like water, the surface of Litercy shimmers. The painting is elusive, furtive, and seemingly transparent and liquid, so much so that it is almost impossible to photograph. Like water, Litercy has the capacity to plunge viewers into a tenuous, vague space: the pool of Narcissus where one is split from one’s self and others, but incapable of leaving the mesmerizing reflection of our own presence in the painting. The missing “a” and the missing “r” in Litercy play another role in this context: both may be understood as forms of diffraction that reinforce the action of the surface of the painting itself, its watery condition. Accordingly, Litercy carries within it — just as the shadows of his White Paintings do — consequential visual, psychological, and narrative meanings, as well as the invisible history of all that has passed before it: its invisible sociological record of art and life.60 Or, as Rauschenberg stated in 1987 about his abiding “obsession” with reflection, mirroring, and projected shadows: “I don’t want the piece to stop on the wall. And it has to somehow document what’s going on in the room and be flexible enough to respond.”61

While it may seem that we have traveled a convoluted path, seemingly far afield from the question of honesty and what is at stake in Rauschenberg’s act in the gap, Litercy takes us to the core of the matter. It sets in motion all that occurs in the gap, before the decision will be made to regard the “something” that Rauschenberg makes as art, and before that art becomes institutionalized as Art. Such circumstances require another detour.

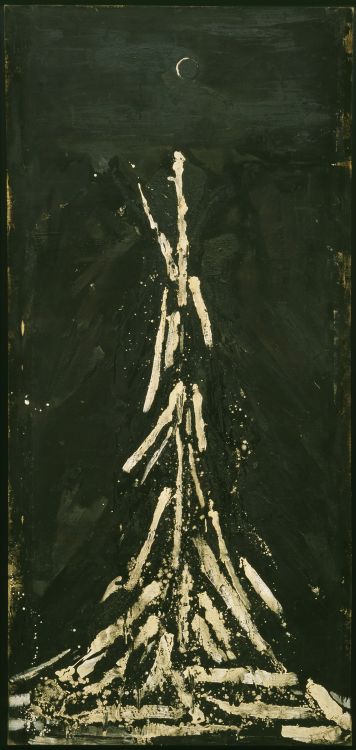

CAT. 57 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), Untitled (Night Blooming), ca. 1951. Oil, asphaltum, and gravel on canvas; 82 1/2 x 38 3/8 inches (209.6 x 97.5 cm). Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York, New York. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York.

Rauschenberg knew very well the difference between “something,” “art,” and “Art,” as a letter he wrote, postmarked October 18, 1951, to the New York art dealer Betty Parsons, proves.62 Written in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina, only four days before turning twenty-six, Rauschenberg explained that “since putting on shoes” he had “sobered up from summer puberty and moonlit smells.”63 The poetry of his opening line refers specifically to his first series of black paintings, works like Untitled (Night Blooming) (ca. 1951; CAT. 57). With its thick sticky surface, pitted with gravel from being pressed wet against the ground, the painting displays a tiny waning crescent moon barely visible above dashes of white paint that symbolize the fragility and brevity of the petals of the night-blooming cereus.64

The lyricism of this line is followed by the power of his next: the White Paintings were “almost an emergency.” After acknowledging that his monochrome paintings were “not Art” because their status as “art has not been” recognized, Rauschenberg asserted that the series was original and “deserves . . . a place with other outstanding paintings” in the history of art. Seizing the moment with youthful confidence, Rauschenberg expressed an urgency to exhibit these paintings “this year.” As part of his persuasion, he boldly risked never exhibiting again in the gallery that prided itself on such artists as Barnett Newman, Clyfford Still, and Ad Reinhardt. He promised to forgo any future exhibition in Parson’s gallery if she would show the new works within the next two months. She did not. Rauschenberg had to wait another twenty-three months before the White Paintings were exhibited at the Stable Gallery in September 1953.

Why did Rauschenberg throw his fate to these works that were not-yet-art, rather than join the vaunted group of abstract expressionists? He grasped the immanent honesty and uniqueness of his work, writing to Parsons: they “take you to a place in painting art has not been.” He followed this declaration with two stunning sentences:

(therefore it is) that is the the [sic] pulse and movement the truth lies in our pecular [sic] preoccupation.65 they are large white (1 white as 1 GOD) canvases . . .66

In making these enraptured pronouncements, Rauschenberg uses parentheses twice, the only place they are used in the entire letter. The parentheses mark off a break from the rest of his thoughts. “(therefore it is)” heralds a sentence later “(1 white as 1 GOD).” This is the same parenthetical technique that he used in his famous statement: “Painting relates to both art and life. Neither can be made. (I try to act in that gap between the two.)” In his use of parentheses, Rauschenberg could be said to have introduced a textual device for framing and for offering readers a visual means through which to enter the gap with him.

Several sentences after (therefore it is) and (1 white as 1 GOD), Rauschenberg becomes perfectly clear about the task that he has set for the White Paintings: “They are a natural response to the current pressures of the faithless and a promoter of intuitional optimism.” Testifying without ambiguity to the role of faith in his life as the source of “intuitional optimism,” Rauschenberg names joy, brightness, and positivity, precisely the same qualities that he continued to promote forty-eight years later in 1999 when he explained that his life came from a place of “hope, courage, and strength” in order that his art “support inspiration and life” (as cited above).67 Rauschenberg never deviated from the aim he expressed in his mid-twenties in 1951. The White Paintings have proved to be momentous for numerous reasons over time, but they must also, and perhaps above all, be understood as the artist’s manifesto of faith, a foundation from which he never waivered, notwithstanding the preponderance of critical and art historical ink to the contrary.

Rauschenberg’s unshakable faith and intuitional optimism appears to have embarrassed many critics, art historians, and curators, who tend to find ways to discuss the works without addressing his potent conviction represented in them. Walter Hopps associated the White Paintings with “rectilinear minimalism and flat surface articulation,” even as he admitted, albeit with a caveat, that in his earlier Crucifixion and Reflection (ca. 1950), Rauschenberg may have suggested “a reconsideration of the iconic meaning of the cross as an abbreviated reflection.”68 Hopps also summons comparisons to “Abstract Expressionist art of this time” and, most curiously, writes about another early work, Mother of God (ca. 1950; see fig. 3):

Although Rauschenberg had no direct connection with the contemporaneous Beat (as in spiritually beatific) world of Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg, this work resonates synchronistically with their mix of seriousness and wildness, spirituality and play, as well as their explicitly American wanderlust. The work reveals that Rauschenberg sees urbanity as part of nature.69

The strained effort to transform Christian references into “urbanity as part of nature,” as well as to connect Rauschenberg to the Beats with whom Rauschenberg “had no direct connection” in 1951, Hopps admits, is proof enough of the lengths to which Hopps felt he needed to go in order to dissociate the artist from the spiritual sentiments that he expressed in his letter to Parsons, the letter that, ironically, Hopps reproduced in full in the very book in which he distances Rauschenberg’s work from such intentions.70

Susan Davidson associates early works like Crucifixion and Reflection and Mother of God with “Abstract Expressionism,” avoids engagement with Rauschenberg’s religious concepts, and calls the White Paintings “proto-Minimalist statements.”71 While her next point is obviously true, Davidson remains resolutely non-committal when she writes: “No single interpretation of these works suffices.”72 Sam Hunter writes off the Christian content of the work altogether. “Rauschenberg’s role in [the White Paintings] is more medium than creator,” Hunter states, and then credits Cage’s “non-volitional esthetic” for the direction that Rauschenberg’s work took even while acknowledging that, while they met in 1951, Cage and Rauschenberg did not become friends until the summer of 1952, and Cage was not at Black Mountain when Rauschenberg made the works in 1951.73 For her part, Mary Lynn Kotz ignores the religious connection to the pre-white and White Paintings altogether.

Only Barbara Rose, Rauschenberg’s close friend for decades, is unapologetic. His depiction of God as a satellite dish for the Vatican, she notes, was Rauschenberg’s effort to show that this object represented “the sacred receiver and broadcaster of all communications.”74 Rose further asserts that all of Rauschenberg’s prolific production, “this manic activity . . . is a vast idealistic project.” His “penchant for ringing certain images with painterly frames” may be nothing less than a way of creating “haloes for what the artist considers sacred.” Moreover, his “acts of the salvation of the humble, the mutilated and the discarded are not arbitrary,” but rather deeds of “a poet who can barely read, a preacher whose sermons are his life and work.” Though he “tried,” Rauschenberg “failed to save the world.” Instead, he “put his best efforts into saving the grand manner and the great tradition of painterly painting.”75

A more moderate position is that of the art historian Branden W. Joseph, who addresses the religious issues in Rauschenberg’s letter to Parsons, even though citing “unpublished notes” from a 1991 interview with Rauschenberg by Hopps that has Rauschenberg testify against himself to a “short lived religious period” in the early 1950s. (Oddly, Hopps does not quote this comment in his essay in his book on Rauschenberg.)76 Nonetheless, Joseph acknowledges that a number of the pre-white and White Paintings seem to be symbolic of the divine, with Rauschenberg’s paintings representing a sort of “incarnation,” a term Joseph credits to the art historian Thierry de Duve.77 Despite admitting the symbolic “divine” in Rauschenberg’s White Paintings, Joseph concludes that the works represent only “the residual traces of religious implications,” and then presses forward with a “modernist” interpretation of them.78

Rauschenberg’s “urgency,” Joseph is at pains to explain, “seems also to have resulted from a newfound engagement with the developmental logic of modernist painting.”79 Joseph then describes Rauschenberg’s “parenthetical, elliptical reminder ‘therefore it is’” as Rauschenberg’s confirmation that the works belong to avant-garde canons of transgression, which Joseph argues is confirmed by the rest of Rauschenberg’s sentence, “that is the . . . pulse and movement[,] the truth [of the] lies in our peculiar preoccupation.”80 This conclusion leads Joseph to interpret the White Paintings as evidence of the “specter” of Clement Greenberg’s 1950 lectures at Black Mountain, which Rauschenberg did not hear, as he was not in attendance at the college at that time. Finally, Joseph reads Rauschenberg’s interest in the monochrome as belonging to the modernist “zero degree of painting.”81 This deduction is based on Rauschenberg’s explanation to Parsons that he was “[d]ealing with the suspense, excitement and body of an organic silence, the restriction and freedom of absence, the plastic fullness of nothing, the point a circle begins and ends.” But Rauschenberg follows this sentence by stating “they are a natural response to the current pressures of the faithless and a promoter of intuitional optimism,” thoughts that have nothing in common with formalism or the “logic of modernist painting.”

Finally, like so many before him, Joseph presumes from Rauschenberg’s language: “[W]e must look . . . to the context of Rauschenberg’s collaborative relationship with John Cage — whom he met in 1951, but would come to know only in the summer of 1952 — . . . to understand this transformation in the discursive framework surrounding the White Paintings.” It is not only Cage that Joseph recommends, but also Cage via Henri Bergson and Antonin Artaud, among other individuals and philosophic traditions. Just as Hopps joins Rauschenberg to the Beats, while acknowledging there is no connection, Joseph links the White Paintings to Cage, who Joseph acknowledges only came into Rauschenberg’s life in a substantive way a year after the paintings were made. It was during this period in the summer of 1952 that Cage, so rapt with the White Paintings, composed 4’33”. Not only impressed by Rauschenberg’s accomplishment, Cage felt that he “must” compose 4’33”, the composition that emphasizes what Rauschenberg identified in the White Paintings as their “organic silence,” otherwise, Cage explained, “I’m lagging.”82

While such distinguished authors as Hopps, Davidson, and Joseph display similar discomfort or ideological conflict with the artist’s determined spiritual relation to his art, Cage was the first to commandeer Rauschenberg’s art away from his faith or spiritual purposes, judging from the leaflet that Cage wrote and had passed out during Rauschenberg’s 1953 exhibition at the Stable Gallery. It read:

To Whom

No subject

No image

No taste

No object

No beauty

No message

No talent

No technique (no why)

No idea

No intention

No art

No feeling

No black

No white (no and)After careful consideration, I have come to the conclusion that there is nothing in these paintings that could not be changed, that they can be seen in any light and are not destroyed by the action of shadows.

JOHN CAGE

Hallelujah! The blind can see again: the water’s fine.83

Rauschenberg seems never to have commented on Cage’s leaflet. Regardless, it is hard to overlook Cage's pervasive pejorative tone or his disparagement of Rauschenberg’s black and white monochromes and Elemental Sculptures as “No talent,” “No idea,” “No art,” “No feeling,” “No black,” or “No white.”84

Rauschenberg’s passion and the innate sophistication of his monochrome works defy Cage’s description, and it is difficult to imagine that Rauschenberg appreciated the leaflet. He was, more likely, perplexed, perhaps even hurt, by its terminology and implications, which were so far from his own aims. Furthermore, as Cage’s list includes “No message” and “No intention,” these terms imply that Rauschenberg’s art had none. What could be farther from the goals of the artist who pondered “(therefore it is),” who conceptualized “(1 white as 1 GOD),” who was concerned about “the pressures of the faithless,” and whose outlook was informed by “intuitional optimism”? Moreover, what could Rauschenberg have thought of Cage’s 1961 discussion of his 1959 statement in Cage’s oft-cited essay “On Robert Rauschenberg, Artist, and His Works”? There, Cage continued in the vein of the 1953 leaflet, describing the “gap” as “the nothingness in between . . . where for no reason at all every practical thing that one actually takes the time to do so stirs up the dregs that they’re no longer sitting as we thought on the bottom.” As if this was not insulting enough, Cage added: “All you need to do is stretch canvas, make the markings and join. You have then turned on the switch that distinguishes man, his ability to change his mind.”85 Given Cage’s deprecation of Rauschenberg’s reverent approach to art and life, Rauschenberg must have suppressed his spiritualism in the composer’s (and other’s) company. It may be telling, however, that following his break with Cage in late 1964, which accompanied his resignation from the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, in 1965 Rauschenberg purchased an orphanage at 381 Lafayette Street in New York and made its chapel his studio.

Cage’s insistence upon inserting himself into the arena of Rauschenberg’s art succeeded in shaping the reception of Rauschenberg’s work. Much more research needs to be done to untangle Rauschenberg from Cage, but in the meantime it is unconvincing to suggest that it is necessary to “look . . . to the context of Rauschenberg’s collaborative relationship with John Cage” for an understanding of Rauschenberg’s work, as Joseph suggests. On the contrary, what must be considered is how Cage shifted the meaning of Rauschenberg’s intentions away from Rauschenberg’s purposes, even as, or perhaps because, Cage knew very well that Rauschenberg often disagreed with him. Merce Cunningham offers a ready example, for instance, of Rauschenberg’s resistance to Cage’s interest in the application of the workings of chance to painting. “You can’t use chance in painting without turning out an intellectual piece,” Rauschenberg told Cage. “You can use it in time, because then you can change time.”86 Given such wrangling, it seems unlikely that Rauschenberg was the person interested in Cage’s 1953 leaflet.

I think that the artist who was drawn to Cage’s text was Ad Reinhardt. Cage’s leaflet reads like notes for what would become Reinhardt’s famous “Twelve Rules for a New Academy,” published in the May 1957 issue of Art News.87 Nonetheless, in earlier publications, the date 1953 is given for the inception of “Twelve Rules for a New Academy.”88 In Reinhardt’s many versions of his biographical “Chronology,” for example, one dated circa 1966 lists 1953 as the year that Reinhardt “[p]aints last paintings in bright colors,”89 while another version, circa 1965, adds that in 1953 he “[gave] up principles of asymmetry and irregularity in painting.”90 What is particularly interesting about the circa 1966 version is that it lists for 1956 the following: “Is called by Emily Genauer ‘a frightening example of a man of talent but with so much ego as to insist that what he refuses to do is more important than what other artists do.’”91 Genauer was none other than the critic who published Cage’s leaflet “in its entirety” in the New York Herald Tribune on December 27, 1953, and she was clearly someone that Reinhardt had enough interest in to add to one version of his Chronology.92

No one has commented to my knowledge on the close relationship between the Cage and Reinhardt texts, and early writers on Reinhardt, like Lucy Lippard, take pains to distance his later monochromes from Rauschenberg’s antecedent monochromes of 1951 to 1953. According to Lippard, Rauschenberg’s monochromes were, for Reinhardt, merely “suggestive, but not necessarily seminal to Reinhardt’s project” because they “were a kind of skeptical nihilism.”93 Lippard closes this commentary by pointing to the fact that “Reinhardt makes no mention of Rauschenberg’s matt black work.”94 I have found no mention either of the fact that Reinhardt’s Black Quadriptych (1955) four-panel painting is identical to Rauschenberg’s four-panel White Painting (1951), both of which join four identically sized canvases together in a larger square. Perhaps more importantly, Lippard insisted that “a distinction should be drawn between the significance that the monochrome held for these artists in the early 1950s.” She concluded: “In contrast to Rauschenberg’s neo-Dadaist gesture, Reinhardt’s monochromes are constructive.”95 But the association of Rauschenberg’s monochromes with a “neo-Dada gesture” has to do with the reconfiguring of their reception in Cage’s leaflet and nothing to do with the actual content Rauschenberg intended for his works. As a photograph of his installation at the Stable Gallery proves, this context was anything but “neo-Dada” and Reinhardt knew that too.

In 1964, Reinhardt mentioned in an interview: “Even when I was writing Twelve Rules for an Academy, and I was setting up the -- it was sort of humorous because there was only one artist that was qualified to be a member of this academy.”96 Reinhardt never explained what the “the” was, nor did he identify the “one artist,” and neither did he ever mention Rauschenberg in the interview. But could the “one artist” have been anyone other than Rauschenberg, even if, by 1957, he had left monochromes long behind? If not Rauschenberg, the “one artist” must have been Reinhardt himself. Rauschenberg later remembered, no doubt with pointed irony, that Barnett Newman “hated” his White Paintings and Reinhardt “hated” his black ones.

Though it is well known that Rauschenberg wanted to be a “preacher” when he was a boy, and though his dealer Leo Castelli claimed at one point, “He still is [a preacher],” what I want to insist is that Rauschenberg was simply a man of faith. As he matured, he drew sustenance from every living creature and every produced thing. The world and everything in it served to increase his endless source of belief that, “Healing with faith is paramount,” as he expressed to Monsignor Mario Codognato in August of 1999. Early on, he set apart a space to enact that faith between the otherwise overwhelming circumstances and demands of art and life, which he later understood as “blinding fact,” a phrase that suggests the more common expression “brute fact,” which stands for something that cannot be explained, something that contradicts the principle of sufficient reason. A statement that Rauschenberg made in 1991 pushes that understanding in yet another direction, one that expands on what “blinding fact” might have meant to him. “Understanding is a form of blindness.” Rauschenberg observed, adding, “Good art, I think, can never be understood.”97

Blinded by the infinite possibility of the fact of art (in its abstract, visible invisibility) and the fact of life (in its literal, experienced reality), Rauschenberg sought ways to get outside, but also to remain in proximity to, these inscrutable totalities, not only for himself but also for his viewers. At the same time, he invented ways to keep the act of “making” a vital pursuit and to bring viewers into the genesis of the “something” that he “tried” to make happen in the gap, with the poignant “understanding” that his and their “acts” might eventually lead to blindness as well.98

I have now come full circle back to Rauschenberg’s 1977 comments to Diamonstein. Especially critical are the next four sentences that he uttered, after first establishing his view of the honesty of the artist. They were:

You love art. You live art. You are art. You do art.

At this moment in the interview, the cadence of his speech changed, and as Rauschenberg spoke these short declarative sentences, he seemed to chant, clapping quietly in time to the sound of each verb: You love art. You live art. You are art. You do art.” This is the most intimate statement that Rauschenberg ever made about his state of mind in the gap. In 1991, he would observe:

Whether I am working in shadows or silks or atrocities or just the street corner, it’s headed toward . . . a realization of “you are here.”99

Focusing on the behavioral and emotional forms of process in life, rather than on its objective ends, Rauschenberg’s clapping enacted the affect that took over when he loved, lived, was, and did “something” in that space where “you’re just doing something [that] no one can stop you from doing” because it “is your life” and it “doesn’t have to be art.” Taken together with his further observation that “you can’t make life,” Rauschenberg separated the process of making an object from making a life. At the same time, he acknowledged that doing is your life, because that is where you love, live, are, and do (in his case) “art.” Rauschenberg’s “act in the gap” thus denotes the distinction of loving, living, being, and doing art, from the disparity between being in life and making life; and he succinctly identified the intersection of mental states in the “act” as differentiated from the social conditions of the ends of production — that is, “how much use you can make of” art.

Many intriguing accounts of Rauschenberg in the studio exist, but none more exhaustive and comprehensive than the valuable contribution of Robert S. Mattison. He explains in detail how the artist drew on the “constant running banter [and] jokes” of his studio assistants to arrive at associations and solutions in his art through “small talk [that was] seemingly unrelated and apparently inconsequential to his immediate activity,100 but whose “common energy” was essential to “his creative process.”101 Mary Lynn Kotz quotes Stanley Grinstein, an art collector, who recalled witnessing Rauschenberg’s energy while working and participating in his own late-night habits, which made “every day . . . like a party. Rauschenberg with a contingent of friends, everybody helping, everybody laughing.”102

Juxtaposing this festive atmosphere with the importance that Rauschenberg gave to organization — “Everything I can organize I do, so I am free to work in chaos, spontaneity, and the not yet done.”103 — provides a fuller picture of the care that he put into systematic organization in order to free himself to see “the not yet done.” In other words, to the best of his ability, Rauschenberg tried to live daily life as if in the gap in order to find what had not yet been discovered or “done.” To reinforce his aim to dwell in the constant present, Rauschenberg kept virtually no earlier examples of his art either at his studio or at his house, explaining, “What interests me is the here and now. . . . Reality is you and I here at this moment.”104

“Few people have the imagination for reality,” Johann Wolfgang von Goethe observed. Rauschenberg was one of those few. For him being in reality was like a creed. “To break down barriers [and] see as an alien does,” he advised, “to get lost in the city, or the country, to see things . . . that maybe you are blind to.”105 Here are the stakes of the gap for Rauschenberg: “I am in the present. . . . The past is part of the present.”106 Dave Hickey would keenly observe that Rauschenberg “invariably devoted all his generosity” to the “task of inventing the present.”107

Over-familiarization with the conventions of living, even with seeing his art hanging on the walls of his own home, threatened to become stultifying to Rauschenberg by proximity. The best example of how anesthetized routine and destruction of imagination both horrified and emotionally affected Rauschenberg comes from his experience in China in 1982, only six years after the soul-crushing Cultural Revolution ended with Mao Zedong’s death in 1976. A shocked Rauschenberg reported: “I think [the Chinese] really were just beaten down. They had exhausted any initiative, any hope of anything changing. Once you kill the curiosity everything else goes.”108 What devastated him even more than witnessing desire and inquisitiveness drained from so many people was “this big water buffalo [working a water wheel] walking around and around and around blindfolded with an old dirty rag. That was his life. If one isn’t moved by that . . . ”109 Rauschenberg never finished his sentence. As his own existence depended on sight, witnessing the huge beast of burden blindfolded wounded and psychologically distressed the artist.

Rauschenberg felt that everything required his keen attention so that he might unlock the simplicity of something’s deceptive complexity, or vice versa, and thereby discover its mystery. This is why, returning to his discussion with Diamonstein, when she asked him if he thought that art rested “more in ideas” than the thing itself, he answered: “The definition of art would have to be more simple-minded than that, and it’s about how much use you can make of it.”110 For the writer Stephen R. Dolan, Rauschenberg implied that “if you can’t make art, you can’t destroy it; creating with the intent to create, which limits creativity; and it’s the action that counts as opposed to its being.” In the end, Dolan observed about Rauschenberg’s aim: “Art’s ‘use’ is in the mileage you get out of leaving what you have made out there for others: that’s where your act is its most effective.”111 The “use” of art, for Rauschenberg, required not sequestering it as Art outside of life, which rendered it “very self-conscious and a blinding fact” for the vaunted social position and prestige that stripped Art of its life. Rauschenberg’s last sentence on the matter delivered a coup de grace: “Life doesn’t really need [art]. So it’s also another blinding fact.” With this closing sentence, the Diamonstein conversation veered off in another direction. But certainly Rauschenberg never had the hubris to believe that life needed the “something” that he made, and so he preserved the “gap.”

Bringing Rauschenberg’s collection of his own art together with selected works in the Nasher Museum’s permanent collection was a unique and welcomed opportunity, notwithstanding the constraints of organizing an interface between two very different bodies of art.112 I am indebted to an early discussion with art historian and Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum curator Susan Davidson, an authority on Rauschenberg, and David White, senior curator for the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, for the language of “collecting and connecting.” These terms succinctly captured my goal to establish the principle of a dialogue between the two collections, and to bring together in conversation overlapping investigations and themes irrespective of medium, social background, and divergent cultural traditions, as well as to challenge viewers to look long at, and think hard about, how similitude enriches difference. I wanted art history to offer room for mutual artistic interests to converge visually, and for previously unimagined perspectives to emerge conceptually, in order to enrich consideration of otherwise undiscoverable commonalities in multiplicity and diversity.

Organizing artworks into “conversations,” I also sought to bypass art historical, pedagogical, and even social norms in which debate over comparisons, as well as demand for proof, often take priority over dialogue. Comparison has long been the model for art history, where judgments of precedent, style, value, and much else, still hold as the primary methodological approach in both teaching and scholarship. Other disciplines have not done much better in overcoming the comparative approach, as discussions of race, class, gender, and sexuality are inevitably framed as adversarial discourses, as are theories of modernism versus postmodernism, postcolonial versus decolonial, and so forth and so on. The goal — from scholarly endeavors to sports — is habitually to use comparison as a means to prevail, a paradigm perpetuated in every aspect of life, from media to museum. By shifting rhetorical strategies from comparison to visual conversation, this exhibition attempts to open the discussion to unconventional relationships among the works and, in so doing, enable the art to be experienced from nuanced alternative standpoints. This opening out of the meaning and interconnection encourages equality rather than competition.

The experience expressed in “AH POEM” by the Russian poet Vsevolod Nekrasov, a member of nonconformist Moscow conceptualism and, for many, “the foremost minimalist to come out of the Soviet literary underground,”113 captures for me the optimum joy and surprise that could be a response to an encounter with the conversations in Rauschenberg: Collecting & Connecting:

Ha haha haha haha

Ah ahah ahah ahahBut ah ahah ahahahah

Ha haha hahahah114

Let me now walk through three rooms in the eight sections of this exhibition in order to present different ways of seeing, and then thinking about, the conversations. Black and White (with Red): Variations on the Monochrome is the first room in the exhibition and takes its motif from three Rauschenberg works: Untitled (Night Blooming), the seven-panel White Painting, and Untitled [matte black triptych] (ca. 1951; see CAT. 56). The addition of the term “(with red)” in the room’s title alludes to the red in the figurative painting by Komar and Melamid, Stalin with Hitler’s Remains. Together these four works begin a chain of multifaceted associations, from Rauschenberg’s approach to the monochrome through a semi-abstract, semi-figurative work like Untitled (Night Blooming), to his austere white and matte-black monochromes, and on to what I have called a “monochrome with-image”: the white monochrome panel hinged to the bottom of Stalin with Hitler’s Remains with the work’s title discreetly printed in block letters across its middle. Taking my cue from Rauschenberg’s term “monochrome no-image,” the phrase he invented to describe his 1953 erasure of Willem de Kooning’s drawing (see fig. 7),115 for the idea of “monochrome with-image,” permit me to invite Yuri Albert into the conversation in this room with his black monochrome About Beauty, its title spelled out in Russian braille.

Together these five works alone could comprise an entire course in the history of modern and contemporary art, from figuration to abstraction, and from non-representational (or monochrome painting and sculpture) to conceptual art. At this point, it becomes possible to see that room one is already embroiled in a lively discussion. But what of the remaining three works in the room: Paul Graham’s Man walking with blue bags, Augusta (2002; see CAT. 35), Ai Weiwei’s Marble Chair (2008; CAT. 1), and Rauschenberg’s own Untitled (Hoarfrost) (1975; see CAT. 77)? It may come as a surprise, but the first conversation I imagined, when selecting works for this exhibition, was the dialogue between Rauschenberg’s seven-panel White Painting and Ai Weiwei’s Marble Chair. Not only are these two works stately in their austere beauty, they are dense in historical meaning.

CAT. 1 Ai Weiwei (b. 1957), Marble Chair, 2008. Marble, 47 1/4 x 22 x 18 1/8 inches (120 x 56 x 46 cm). Collection of the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina. Museum purchase with funds provided by the estate of Wallace Fowlie, 2011.15.1. © Ai Weiwei. Photo by Peter Paul Geoffrion.

Marble Chair derives from the life of the artist’s father Ai Qing (1910–1996), a poet educated in Paris between 1928 and 1932, and one of the founders of modern Chinese poetry. In 1957, Ai Qing was denounced for “rightism,” despite being a communist, and banished as an enemy of the state with his wife and one-year-old baby (Ai Weiwei) to a remote town near the Gobi Desert. There, for nearly two decades, he was consigned to clean public toilets for a village of about 200 people. One of the only objects Ai Qing was permitted to bring into exile was a Qing Dynasty (1644–1911) yoke-back chair. That chair was the model for Marble Chair. After Mao Zedong’s death in 1976, when Ai Weiwei was nineteen, the family moved to Beijing. Thirty-one years later in 2007, Ai Weiwei was invited to participate in the international exhibition Documenta 12 in Kassel, Germany. As a section of his three-part installation Fairytale, he included 1,001 wooden Qing Dynasty chairs positioned as “stations of reflection” in and around Kassel, especially for use by the 1,001 ordinary Chinese citizens that he also brought to Kassel for the exhibition. Ai Weiwei then commissioned an edition of sixty handcrafted marble chairs, each carved from a single block of marble. In China, white is the color of mourning and funerals. White marble was used for terraces in ancient Chinese royal buildings and may also have associations with rank. In these ways, Ai Weiwei honored his father.