« Previous Essay

Rauschenberg’s Photography: Documenting and Abstracting the Authentic Experience

CAT. 12 Bruce Conner (1933–2008), BREAKAWAY, 1966 (still, detail)

Bruce Conner produced twenty-five films between 1958 and 2008, leaving a documentary on the famous gospel singers The Soul Stirrers unfinished at the time of his death, and in the trust of the filmmaker Michelle Silva to finish. Conner experimented largely in black and white with both found and self-produced footage, and worked with original and pre-existing musical tracks. From a formal and thematic standpoint, Conner’s films have little in common. Yet despite their stylistic differences and range of content, the films share an underlying organizational structure. Silva, with whom Conner worked on his films from 2003 until his death, summarized Conner’s style this way: “He created literally a cinematic slot machine . . . images meet, they diverge, and they meet again . . . his editing style ensures that the viewer will never experience the work the same way twice.”1 Silva refers to Conner’s deconstructive editing methods, which include repeating frames, playing frames in reverse, and combining frames with flashing leader edited in a rhythmic pattern that forges an emotive connection to the film’s corresponding soundtrack. Conner himself admitted that his cinematic style was an outgrowth of his collage, itself a foundation for assemblage: “Well of course, the films themselves are collections like assemblage which I did make in the 1950s.”2 The film theorist Bruce Jenkins described the results of Conner’s editing as “an artwork as much as it is a motion picture.”3

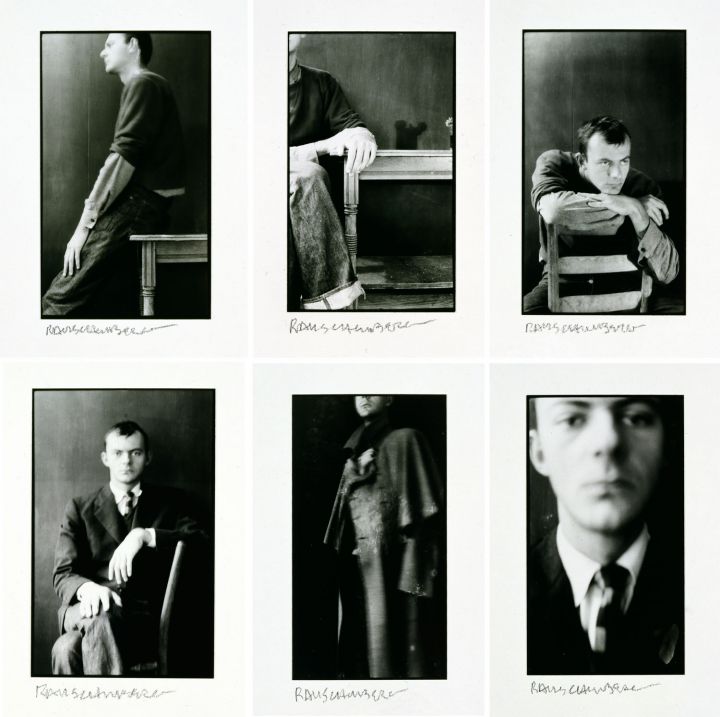

CAT. 61 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), Portfolio II (I–VI), 1952 (printed 1998). Six gelatin silver contact prints mounted on paperboard, 5 5/8 x 3 1/4 inches each (14.3 x 8.3 cm). Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York, New York. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York.

Conner’s handmade films must be understood as an extension of his own visual artworks, as well as in dialogue with contemporary art and avant-garde film. More specifically, a strong correlation exists between Conner and Robert Rauschenberg, whose silkscreen works have a distinct filmic quality. Indeed, the diversity of imagery and kinetic energy of Rauschenberg’s art in all mediums evokes a kind of “channel surfing,” as well as the temporal frame-by-frame development of film.4 There is a remarkable affinity between Conner’s quick editing, appropriation of images of popular culture, and recombination of commercial films and Rauschenberg’s transfer, cropping, and juxtaposition of images from everyday life.

Rauschenberg, too, used his own photography in fragments and montage that invoke a visual virtual kinetics. An interest in kinetic imagery is evident even in Rauschenberg’s earliest photographs. For example, the photographs he took of Cy Twombly at Black Mountain College in Portfolio II (I–VI) (1952; CAT. 61) resemble a series of film stills as Twombly continuously reorients himself within a defined space, his pose and clothing varying from picture to picture. Brian O’Doherty once likened Rauschenberg’s early works, especially his Combines, to “the perceptual modality initiated by film, television, and advertising.”5 The artist’s close examination of temporal movement and his reflection of popular culture initiated new approaches to artmaking that filmmakers could also adopt.

fig. 14 Bruce Conner (1933–2008), A MOVIE, 1958 (stills). 16mm film (black and white, sound), 12:00 minute loop. © Conner Family Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, New York. Courtesy the Conner Family Trust, San Francisco, California and Kohn Gallery, Los Angeles, California.

When asked why he began making films, especially his first film, A MOVIE (1958; fig. 14), Conner explained that he had “waited for someone to make that movie,” but that when “no one did . . . I decided it was my job to make A MOVIE.”6 The film begins with an introduction and countdown, which leads directly into a frame that reads “The End,” despite the fact that A MOVIE continues for another ten minutes. Footage of men riding horseback, galloping over hillsides in high-speed chase scenes, is followed by clips of destructive automobile races with cars spinning out of control, flipping over and being enveloped in clouds of dust. Conner pairs this opening footage with Ottorino Respighi’s fast-paced first movement of his symphony Pines of Rome (1924) to exaggerate the urgency and violence of the filmic action. Approximately two and a half minutes into A MOVIE, a car speeds off the edge of a cliff and crashes down rocky terrain before dropping off into a valley. This scene fades into a frame that announces the end of the film for the second time. The suspenseful, high-pitched musical score ceases, and after a frame that reads “A Movie” flashes on the screen, Respighi’s slower, ominous second movement begins.

The nine minutes of A MOVIE that remain, often referred to as its second half, encompass a wide range of imagery, including movies of water skiing accidents, footage of planes exploding in air, and a clip of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge oscillating and collapsing. Conner interspersed these flashes of death and destruction with tightrope walkers, men playfully riding tricycles, surfers and parachuters in action, and a short glimpse of soft-core pornography. “Conner’s judicious choice of sound excerpts enhances the drama inherent in each found scene,” William Moritz and Beverly O’Neill observe, adding, “In the tight-rope walking sequence . . . the fear the acrobats will fall is allayed by the music’s [Respighi’s second movement’s] delicate, mysterious tones emphasizing the moment's truly magical and gravity-defying properties.”7 Near the end of the film, underwater footage shows scuba divers encountering schools of fish and exploring a shipwreck overcome with algae, barnacles, and seaweed, suggesting new life amidst the wreckage of humankind. Conner ends A MOVIE with sunlight glistening on the water’s surface shot from below, an image synchronized with Respighi’s fourth and last movement as the film fades to black and trumpets triumphantly declare its end.

Referring to Respighi’s music and his own found footage, from newsreel and Castle Home Movies to dramatic films and westerns, Conner modestly, but honestly, said: “The only thing I made, and what I own, are the splices.” Highlighting the tension between ownership and appropriation, Conner projected his name in capital letters for thirty seconds at the commencement of the film, later commenting that it was “silly [because] Bruce Conner doesn’t own any of that film.”8 Conner’s editing genius, his rejection of classical filmic narrative, and his defiance of traditional filmmaking practices were, indeed, all his own trademarks. His bold decision to use blank film leader as an image reveals the artist’s hand, exposing how he rejected standard filmmaking procedures, leaving invention open.9

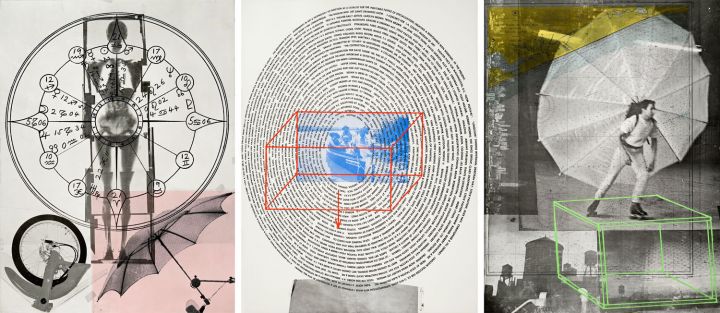

Thinking about Rauschenberg’s relation to Conner’s film work, one must recall that Rauschenberg’s “flatbed” method contributed to viewing visual imagery in a horizontal rather than vertical way.10 This horizontal approach lent painting, collage, and assemblage to filmic time. Already in his first Combines of 1954, Rauschenberg drew on and organized seemingly random materials into a montage-like format, throwing into question the meaning of ownership and originality, all the while being completely unique. In this regard, Rauschenberg’s three-paneled lithograph Autobiography (1968; CAT. 66) is inherently similar to A MOVIE in its organizational structure. The first panel of Autobiography includes a lithographic transfer of an X-ray of Rauschenberg’s skeleton, overlaid with a chart for his astrological sign, Libra, and two other images that recur frequently in his work, a bicycle tire and a photographer’s strobe light umbrella. The second panel features a fingerprint-like whorl of text that lists key moments in Rauschenberg’s life, describing major personal and professional events. A childhood photograph of Rauschenberg boating with his family, silkscreened in blue, interrupts the spiral of words at its center, and the red outline of a block and a downward-pointing arrow superimposed on the image determine its orientation. The third and final panel includes a photograph of Rauschenberg on roller-skates with a parachute-like apparatus radiating from his back in Pelican (1963), a performance he choreographed to a score he created from found radio, music, and television sounds. Images of skylines from New York and Rauschenberg’s hometown of Port Arthur, Texas, flank the photograph, which is overlaid with the outline of a cube.

CAT. 66 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), Autobiography, 1968. Offset lithograph on paper, 66 1/8 x 145 1/2 inches overall (168 x 369.5 cm), 66 1/8 x 48 3/4 inches each (168 x 123.8 cm). Collection of the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina. Gift of Marian B. Javits, 1991.15.1. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York. Photo by Peter Paul Geoffrion.

While Autobiography and A MOVIE differ in visual content and medium, both works share structural and temporal similarities, telling a story while simultaneously remaining open to interpretation. Thus, the print (Autobiography) parallels the film (A MOVIE) in its presentation of a loose non-sequential narrative arranged to be hung either vertically or horizontally in a frame-by-frame format; and A MOVIE parallels Autobiography in being a work of filmic art that emerged from the combined discoveries of Rauschenberg and other artists working in painting and photography. These artists laid the groundwork for avant-garde film by Conner and others like Stan Brakhage and Carolee Schneemann.

fig. 15 Bruce Conner (1933–2008), REPORT (BEGINNING AND CONCLUSION), 1963–67 (still). 16 mm film transferred to video (black and white, sound), 13:00 minute loop. Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina. Promised gift of anonymous donor, L.15.2013.1. © Conner Family Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, New York. Image courtesy the Conner Family Trust, San Francisco, California and Kohn Gallery, Los Angeles, California.

Both Conner and Rauschenberg also incorporated historical events in their imagery, commenting obliquely on the political conditions of their time. In his quasi-documentary film REPORT (1963–67; fig. 15), Conner meditated on President John F. Kennedy’s assassination in an effort to come to intellectual, emotional, and aesthetic terms with the President’s death on November 22, 1963 in Dallas, Texas.11 Appropriating segments of newsreels showing the Dallas parade route before, during, and after the assassination, Conner repeated selected frames, methodically dissecting the few minutes of the murder.12 REPORT begins with footage of the President and First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy waving from the back of the presidential limousine as they drive through the streets of Dallas on the day of his death. The car’s sleek black hood, flanked by miniature American flags precedes Jacqueline Kennedy’s smile and the President’s casual wave, only to disappear in seconds as their car continues on, leaving the cameraman behind. Conner paired this footage with an audio track of a panicked radio announcer who eventually confirms, “There has been a shooting.”

Repeating the shot of the motorcade, Conner’s fast editing imbues the President’s limousine with a staccato-like motion that replicates the emotional experience of the tragic event as it recurs in memory. Flashing film leader then appears as the narrator becomes increasingly anxious. Combining historical fact and feelings, REPORT includes two of Conner’s signature cinematic devices: alternating black and clear leader, flashing at an increasingly fast speed; and using academy leader countdowns to punctuate the passing time.13 The second half of REPORT contains metaphorically charged stock footage of a fallen matador being carried off by spectators, a man climbing a telephone pole to mount an American flag on top, and a drop of milk splashing upwards in slow motion. REPORT culminates in the image of a young woman pressing a button marked “sell,” while the last words of the audio describe Kennedy “heading downtown to the Trade Mart,” a moment that some critics argue represents the commercialization of Kennedy’s persona and death.

Bruce Jenkins argues, “The epilogue is filled with brilliant examples of Duchampian mismatches of image and sound, of logic and meaning, each of which serves to expose the workings of the normally over-determined system of mass communications and its role in shaping public opinion.”14 But rather than Duchamp, Conner’s editing could be said to be more closely aligned with that of Rauschenberg; in particular, REPORT resonates strongly with Rauschenberg’s painting Retroactive I (1963). Retroactive I includes a press photograph of John F. Kennedy speaking at a televised news conference. Rendered in blue with only Kennedy’s tie painted in green, Rauschenberg juxtaposed the President with an astronaut parachuting in mid-air, a yellow image of a box of oranges, and a green image of a glass of what appears to be milk. A hazy grey cloud of paint, which some have imagined as a mushroom cloud, hovers above Kennedy’s head, obscuring a black and white photograph of a construction worker in a hard hat. Kennedy’s extended index finger points to a red enlargement of the 1962 photograph by Gjon Mili published in Life magazine and composed of successive frames of a single figure in movement.15

Conner’s appropriation in REPORT corresponds to Rauschenberg’s appropriation of the Mili and other photographs in Retroactive I. Both artists edit and contrast pre-existing visual content as a means to surreptitiously comment on contemporary events. Rauschenberg’s description of his work as “retroactive” is related to this stylistic approach, as well as to the fact that he began the print before Kennedy’s death, struggled with whether to finish the work after the President’s assassination, and finally “retroactively” felt the need to reflect on historical events.16 “I was bombarded with TV sets and magazines by the excess of the world,” Rauschenberg explained. “I thought an honest work should incorporate all of these elements, which were and are a reality.”17

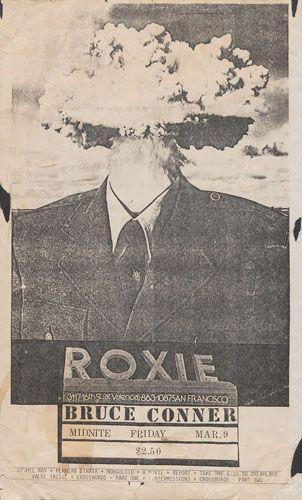

CAT. 33 Bruce Conner (1933–2008), BRUCE CONNER MIDNITE FRIDAY, MAR. 9 . . . , 1979. Xerox flyer, 13 1/2 x 8 1/2 inches (34.3 x 21.6 cm). Collection of the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina. © Conner Family Trust, San Francisco, California / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, New York.

With its grainy quality, disjointed combination of photographs and status as an “emblematic reading as the embodiment of a national tragedy,”18 Retroactive I set a standard for the representation of political events that Conner would pursue in his film CROSSROADS (1976).19 Made with declassified footage from “Operation Crossroads” — the 1946 American military test of two hydrogen bombs in the Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands, a site of many U.S. tests in the 1940s and 1950s — CROSSROADS is Conner’s longest and slowest cinematic work. With its twenty-three shots of the same nuclear explosion shown from a variety of different angles, CROSSROADS reminds viewers of the dichotomy of the bomb’s fascinating beauty and horrific violence. Addressing the threat of nuclear annihilation, Conner selected a closing shot in which nothing is visible but white mist and the vague silhouette of a ship. In 1979, Conner used a still from CROSSROADS for a flyer announcing a screening of his films at the Roxie Theater in San Francisco, collaging the powerful image of the mushroom cloud as his head over a photograph of himself in a military jacket and a tie with a symbol of an atom on it. Nonetheless, he refused to be held to any singular political message, remarking, “When I talk about [the films], I talk about the process [of] making them, or the way they affect other people.”20

Rauschenberg, too, addressed war in his 1971 Poster for Peace. The silkscreen includes a cacophony of images, from a wave, a dead bird, and a torn newspaper clipping to two horizontal black and white photographs of a curtain and two vertical photographs of a telephone, both reading like filmstrips. A black and white image of a hand with nails painted black holds a lit match, and a skull with cartoon light bulbs above it appears in the bottom-right corner of the poster. Below the skull, the word “by” is positioned above violent red ink markings, as if the name of an author has been crossed-out. This trio of images suggests the death of ideas and authorship, and implies a loss of artistic creation in the wake of war and violence. But Rauschenberg also intended for his poster to provoke action by the viewer. To encourage this, he outlined two empty rectangles and wrote a message around the smaller box: “CUT THE WORD ‘PEACE’ FROM ANY FRONT PAGE HEADLINE AND GLUE IT INTO THIS SPACE / CUT IT OUT AND GIVE A PARTY. . . .” Above the larger box, he wrote: “GLUE INTO THIS SPACE — ANY ASSORTMENT OF INFORMATION FROM ANY SINGLE DAYS NEWSPAPER.”

CAT. 12 Bruce Conner (1933–2008), BREAKAWAY, 1966 (still). 16 mm transferred to video (black and white, sound), 5:00 minute loop. Courtesy of the Conner Family Trust, San Francisco, California and Kohn Gallery, Los Angeles, California. © Conner Family Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, New York.

Rauschenberg’s and Conner’s direct efforts to address assassination, nuclear war, and peace were rare in both artists’ oeuvres. Even more rare, for Conner, was to work with a live model as he did in his 1966 film BREAKAWAY (CAT. 12), his film of the twenty-three-year-old singer Antonia Christina Basilotta — better known as Toni Basil — dancing provocatively to her own pop hit “Breakaway” composed by Ed Cobb. Conner’s high contrast work shows the beautiful, sultry singer spinning and thrashing against a sea of black as she sings “I’ve got to get away, I’ve got to break away.” Basil first appears in a series of striking poses aimed to seduce the filmmaker, wearing a black lace bra and dark leggings with circular cutouts that reveal her bare legs. Through his precise editing, Conner increasingly fragments Basil’s seductive striptease until, at the climax of the song, she leaps nude with outstretched arms into the air in a protracted thirty-six-frames-per-second image, while her voice belts the last words of the line: “I’m gonna break away from all the chains that bind, and everyday I’ll wear what I want and do what suits me fine.” Conner’s abstract depiction of Basil rhythmically moving to the sound of her voice-over is hypnotic and highly erotic.21 As Anthony Reveaux writes, “The camera captures her movements in gestural, expressive light smears. . . . Intercut rhythmically with strophes of black leader, she gyrates in graceful, stroboscopic accelerations.”22 The apparition of Basil’s body, together with Conner’s controlled cutting and splicing techniques, reach an apogee in repetition and reiteration of structure, form, and meaning.23

Rauschenberg’s unique methods of transferring photographic imagery parallel the production of such abstract imagery in film. The experimental and innovative materials that he employed throughout his career heighten this level of abstraction, especially in the 1980s and 1990s, when he worked with reflective metals. This practice is particularly vivid in Litercy (Phantom) (1991; see CAT. 87).24 Created by transferring silkscreen negatives onto mirrored aluminum using clear epoxy, Litercy pictures a man with his back to the camera, a tree in bloom, and an obscured sign that reads “wate[r].” These images share the surface with a negative version of Rauschenberg’s 1980 photograph New Jersey, which contains two found building signs: “Bob’s” and “Hand.” Photographing the two together to read “Bob’s Hand,” Rauschenberg included the graphic sign of a pointed index finger in the frame. Litercy could be said to deploy visual strategies and mirroring that are akin to Conner’s reversal and repetition of sound and imagery halfway through BREAKAWAY.

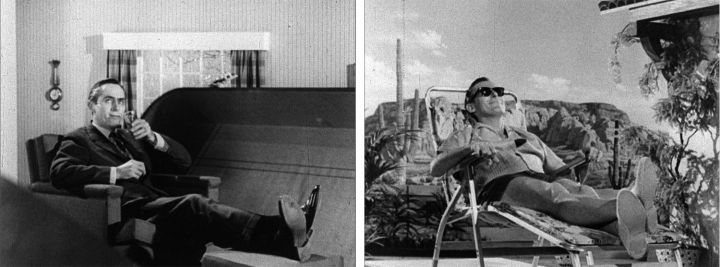

fig. 16 Bruce Conner (1933–2008), MONGOLOID, 1978 (stills). 16mm film (black and white, sound), 3:30 minute loop. © Conner Family Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, New York. Courtesy the Conner Family Trust, San Francisco, California and Kohn Gallery, Los Angeles, California.

Rauschenberg and Conner also shared an interest in the transformation of mundane elements, an inclination that both artists inherited from Surrealism, with its commitment to recovering the sur-reality invisible to, but a component of, all aspects of everyday life.25 Surrealism is perhaps most apparent in Conner’s film MONGOLOID (1978; fig. 16), a film set to the sardonic, socially critical song of the same name by the new wave band DEVO. MONGOLOID represents Conner’s return to films timed to the beat of music, as his calculated use of found footage is suggestive of the narrative lyrics. The song contemptuously describes a man who leads a normal life as if he is a person with Down syndrome, or someone with “one chromosome too many.” DEVO repeatedly sings: “Mongoloid, he was a mongoloid, happier than you and me. And he wore a hat, and he had a job, and he brought home the bacon, so that no one knew.” Derisively and irreverently mocking social conformity as a cognitive disability, Conner captures DEVO’s lyrics in a series of images of an average businessmen with a suitcase closing over his head as he fantasizes in his office about being transported to a lounge chair in a tropical locale.26

Editing his images to the beat of music, and relying on sound and rhythm as an organizing principle of his films, Conner anticipated music videos and MTV by thirty years.27 The mass production of music videos earned Conner’s extreme animosity, and he was reported to have quipped: “I’m called the Father of MTV but I want a blood test; and if I am the father of MTV I should have used a thicker condom.”28 Conner’s putative rejection of his paternity of MTV recalls how, when the Ford Foundation awarded him a $10,000 grant for filmmaking in 1964, Conner — ever the contrarian — made LEADER (1964), a movie using only film leader and intended by the artist “to ruin my reputation as a filmmaker.”29

Despite his best efforts to undermine his own success, Conner’s reputation as a filmmaker flourished, and he is rightfully considered one of the most influential filmmakers in the history of avant-garde cinema. Rauschenberg was similarly resistant to being typecast. Upon winning the International Grand Prize in painting at the Venice Biennale, he immediately telephoned his assistant, Tony Holder, and instructed him to destroy the remaining 150 silkscreens in his New York studio as a preventative measure against self-repetition. Clearly, Conner and Rauschenberg had much more in common than film and filmic time. In this sense, it is all the more intriguing that Rauschenberg was also engaged with musical culture, and was invited in 1977 by the new wave band Talking Heads to design the jacket for their album Speaking in Tongues. It was released in 1983, and Rauschenberg won a Grammy for his design. That Rauschenberg and Conner shared the context of new wave is confirmed by a meeting of the two artists in 1977, when Conner arrived at the opening of Rauschenberg’s retrospective at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and signed the back of the shirt that Rauschenberg was wearing.30

« Previous Essay

Rauschenberg’s Photography: Documenting and Abstracting the Authentic Experience