« Previous Essay

Soviet/American Array: Robert Rauschenberg and Soviet Unofficial Artists

Next Essay »

I Am If I Say So, Bob & Bruce

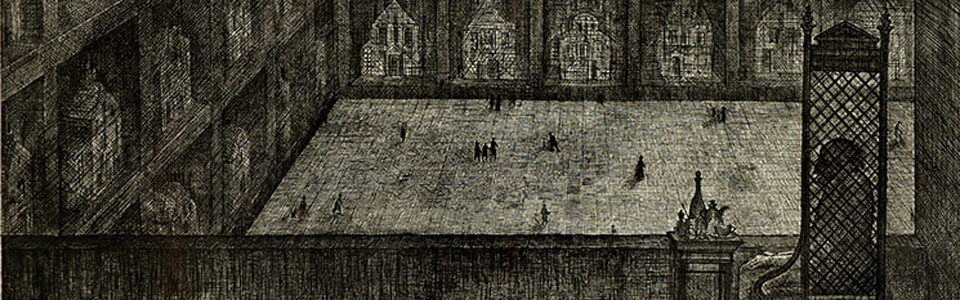

CAT. 6 Alexander Brodsky and Ilya Utkin (b. 1955 and b. 1955), Columbarium Habitabile from the portfolio Projects, 1989 (printed 1990) (detail)

The Russian artists Alexander Brodsky and Ilya Utkin met while students at the Moscow Architectural Institute (MArchI).1 By the time they graduated in 1978, the hardline communist Leonid Brezhnev had succeeded Nikita Khrushchev as First Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party. Brezhnev governed the Soviet Union with an iron hand and continued the “purely utilitarian” architectural style that Khrushchev had instituted after Joseph Stalin’s death in 1953.2 Stalin had commissioned numerous neoclassical edifices known as “Empire Style” that were meant to evoke the image of Soviet power, prosperity, and cultural sophistication. However, he neglected to develop housing projects and left the population in cramped communal apartments. Khrushchev made it his business to provide cheap mass housing, razing many fine eighteenth- and nineteenth-century homes, which he replaced with multi-block apartments that, though bleak and uniform, provided citizens with their own flats.3 Although their contemporaries considered Stalinist architecture “in hideous bad taste,” Brodsky and Utkin “always loved it” for its modicum of quality over the drab Khrushchev-era buildings.4

Once Brodsky and Utkin entered the professional world, they learned firsthand the restrictions on creativity and individuality imposed on Soviet architects; during the three years that they worked in an architectural office in Moscow “nothing [they designed] was built.”5 Instead, they were charged with designing details for preconceived structures and worked “with an enormous bureaucracy.”6 “You’re not free,” Brodsky remembered. “You do something, then you have to show it to everybody above, and they all make changes. Then there’s the frustration — if they build it — of explaining, ‘It’s not my project.’”7

To preserve their integrity, Brodsky and Utkin began creating fantastical structures in exquisite and detailed drawings, which they submitted to international architectural competitions and for which they began “collecting awards, to the juror’s amazement, not to mention that of the designers themselves.”8 Together, with other colleagues inventing similar fanciful structures on paper, Brodsky and Utkin earned the title of “Paper Architects.”9 Initially a “derogatory term used to berate the Soviet avant-garde of the 1930s,” the title came to be a badge of honor by the 1980s.10 Like other young Paper Architects, Brodsky and Utkin embraced their label and continued to enter competitions, gaining the creative freedom denied by the Soviet state. On the whole, their works exhibit what Leah Ollman describes as a “nostalgia” for the traditions of old Russia, whose “lost values” they preserve in etchings that display a longing for classical building materials like marble and glass.11 Brodsky remarked: “We long to work in stone.”12 Stone or no stone, Brodsky and Utkin remain undaunted. “There’s nothing in our projects . . . that couldn’t be built,” They explained. “We’ve always secretly hoped that some day we could build one of them. For no reason at all.”13

In 1989 and 1990, Brodsky and Utkin put together their portfolio Projects, a corpus of some thirty-five etchings. These works attest to their status as “architects of the imagination,” the term Jamey Gambrell used to described them.14 Brodsky and Utkin derived their unusual designs from brief descriptions of conceptual themes the competitions they entered imposed on contestants.15 While still never having constructed a building, the pair were admitted to the Architects Union in the 1980s based solely on their prize-winning etchings, all of which follow a similar formula with “trademark architectural elements — the frontal view, the section, the aerial, the plan.”16 In addition, on each etching a short, descriptive text functions as an architectural label. The art historian Robert L. Pincus described the artists’ intentions this way: “[T]heir art is not about architecture, in any technical sense. It is an argument for a new sense of play . . . ask[ing] us to revive a concept of the city popular in the 18th and 19th centuries: of the metropolis as theater.”17 The four etchings discussed here from Projects contain references to classical mythology or Greco-Roman architecture and sculpture, buildings the pair primarily knew from photographs and magazines as Soviet travel restrictions prevented them from travel abroad. These four etchings represent Brodsky and Utkin’s theater. But rather than understood as “play,” they offer sobering critiques of oppression and inspiring examples of the survival of the imagination.

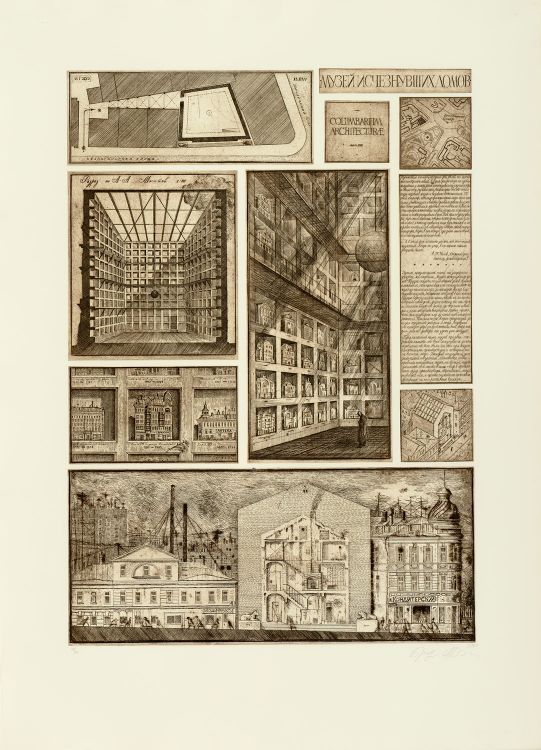

Columbarium Architecture (1984; CAT. 4) shows several views of a “Museum of Disappearing Buildings.” Brodsky and Utkin invented the recessed vaults of a columbarium in an attempt to lay out an edifice for the funerary storage and preservation of countless antique buildings destroyed by the Soviet government and replaced with poorly constructed, concrete, box-like, system-built apartment complexes.18 Columbarium Architecture includes a typical city plan with aerial, frontal, and section views; white borders divide its ten sections, each with a separate image. The two largest divisions present a frontal view of the building and a more detailed look into the interior courtyard. Four divisions comprise the upper band, two of which include text. One division shows a bird’s-eye view of the structure that hints at the irregular plan of the columbarium with its discrete side entrance and dominating large courtyard or plaza. In the middle ground, a view of the empty columbarium, its walls filled with uniform niches large enough to hold a six-storied house, can also be seen in the detail of three alcoves, each occupied by a distinct ornate home and labeled with the original location and lifespan of the structure. Another view shows a corner of the towering courtyard with its numerous boxes, some of which are empty, but most of which contain a unique home. A visitor stands in the middle of the space, staring at one of the homes as if mourning the implications of the wrecking ball hovering above. The etching’s companion drawing Columbarium Habitabile, to which I shall soon turn, elaborates on the story of the wrecking ball.

CAT. 4 Alexander Brodsky and Ilya Utkin (b. 1955 and b. 1955), Columbarium Architecture (Museum of Disappearing Buildings) from the portfolio Projects, 1984 (printed 1990). Etching on paper, edition 18/30, 42 1/4 x 30 3/4 inches (107.3 x 78.1 cm). Collection of the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina. Museum purchase, 1995.12.3. Art © Alexander Sawich Brodsky and Ilya Utkin / RAO, Moscow / VAGA, New York, New York. Photo by Peter Paul Geoffrion.

A central text offers the objective of the “Museum of Disappearing Buildings,” together with an excerpt from Anton Chekhov’s The Old House (A Story Told by a Houseowner) (1887):

They had to tear down an old house in order to build a new one in its place. I led the architect through the empty rooms and among other things told him various stories. Torn wallpaper, dirty windows, blackened furnaces—all this bore the traces of recent life and evoked memories. On this very staircase, for instance, a drunken group once carried a dead man; they tripped and tumbled downstairs along with the coffin; the living were painfully bruised, but the deceased was very serious and shook his head as if nothing had happened when they lifted him from the floor and placed him in the coffin once again. There are three doors in a row: young ladies lived there; and as the frequently entertained guests, they dressed better than all the other inhabitants and punctually paid the rent. The door at the end of the hallway leads to the laundry where they washed clothes during the daytime and at night drank beer . . . and in this room a poor musician lived for ten years. When he died they found twenty thousand in his feather bed.19

This excerpt emphasizes residents’ memories of buildings and the structures worthy of preservation. To Chekhov’s text, Brodsky and Utkin add:

The museum that we propose is called upon to preserve the memory of all disappearing buildings, regardless of whether, during their lifetime, they were architectural monuments or were visited by great and famous people. Each disappearing building, even the most unprepossessing, is an equal exhibit in the museum. After all, each is suffused with the soul of its architect, builders, inhabitants, and even the passersby who happened to cast an absent-minded glance its way.20

Attesting to the significance of history in living memory and the indisputable value of the architectural past in the lives of residents and citizens at large, the façade of the columbarium resembles a traditional interior of a three-story house. This unconventional frontage blurs public and private space typical of how countless Soviet families of all classes lived in communal apartments, sharing everything with little privacy. These dreary complexes all had a courtyard of the type in this etching where children played and residents socialized, designed to enable everyone to know everything about everyone else. In Columbarium Architecture, Brodsky and Utkin appropriate aspects of Soviet housing to expose its architecture of surveillance, destruction of the past, and ruination of tradition.

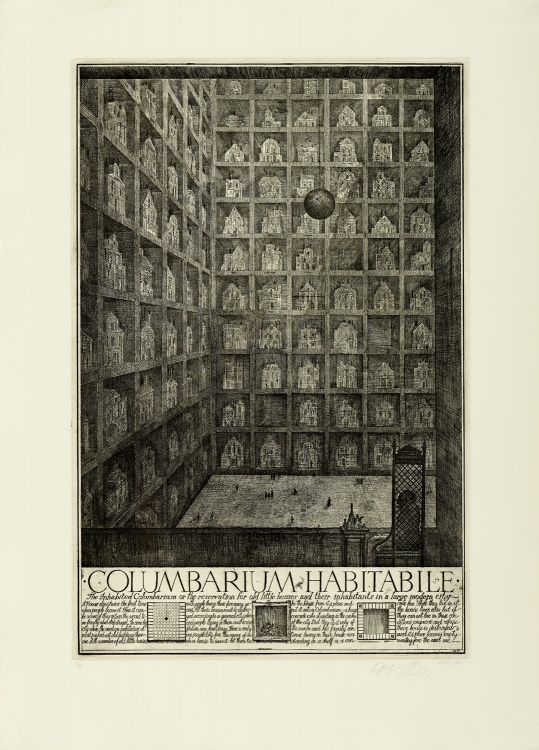

In Columbarium Habitabile (1989; CAT. 6), Brodsky and Utkin concentrate more closely on the “Museum of Disappearing Buildings.” The wrecking ball of Columbarium Architecture menaces some eight stories above the courtyard, like the tyranny of the state ready to smash its citizens. The etching’s text explains that if occupants abandon their home in the columbarium, the building will be demolished, leaving a niche free for a new house and family. The floor of the gigantic room is strewn with tiny residents and visitors scurrying about like insects beneath the destroyer. An unidentified figure in the foreground sits in a large chair with a table laid out for tea, looking out at an imposing courtyard. The high lattice back of his chair, together with his leisurely attitude, gives the figure a somewhat official presence. Does he control the fate of the houses, survey the activities of their inhabitants, or rest in the interstice of their fate? Through his eyes, viewers contemplate the destiny of the homes on the brink of disappearance.

CAT. 6 Alexander Brodsky and Ilya Utkin (b. 1955 and b. 1955), Columbarium Habitabile from the portfolio Projects, 1989 (printed 1990). Etching on paper, edition 18/30, 42 1/4 x 30 3/4 inches (107.3 x 78.1 cm). Collection of the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina. Museum purchase, 1995.12.4. Art © Alexander Sawich Brodsky and Ilya Utkin / RAO, Moscow / VAGA, New York, New York. Photo by Peter Paul Geoffrion.

At the base of the etching, the plate’s title appears in large block letters, together with a melancholy text by Brodsky and Utkin:

A House dies twice—the first time when people leave it[;] then it can be saved if they return. The second time finally when it’s destroyed. . . . In some big city where the modern architecture almost pushed out old buildings there are still a number of old little houses with people living there for many years. All these houses must be destroyed according to a general city plan and the people living in them must [re]ceive flats in new buildings. There is only one possibility for the owner of such a house to save it: let them take the house and put into a Columbarium—a huge concrete cube standing in the center of the city. But they do it only if the owner and his family continue living in their house—now standing on a shelf in a concrete box. While they live in it the house lives also . . . but if they cannot live in these conditions any more and refuse their house is destroyed . . . and its place becomes empty waiting for the next one.21

With clarity and brevity, these Paper Architects describe the Soviet attitude toward the old Moscow buildings and the imperative of the “general city plan” to destroy them. Evicted and directed to an apartment, tiny and dull in a new complex, the animate effect of the old home recalls Arjun Appadurai’s review of how “things” attain value and political currency: “Value is embodied in commodities that are exchanged [which] makes it possible to argue that what creates the link between exchange and value is politics, construed broadly [and that] justifies the conceit that commodities, like persons, have social lives.”22 Appadurai makes it clear that “things” — for him — “have no meanings apart from those that human transactions, attributions, and motivations endow them with.”23 Nevertheless, he admits that from the perspective of the “anthropological problem,” objects do have meaning “inscribed in their forms, their uses, their trajectories” and that understanding these paths enables one to “interpret the human transactions and calculations that enliven things,” as well as grasp from a “methodological point of view [that] it is the things-in-motion that illuminate their human and social context.”24

Poignantly visualizing the human animation of a home in Columbarium Habitabile, Brodsky and Utkin also address the purpose of their fictional museum: its politics. If a home is about to be demolished, residents can choose to save it by moving into the columbarium. But at what cost? The artists suggest that the price is their lives. Enduring the paradox of purgatory in a Marxist state, the souls of sinners will never be expiated, will never pass on to heaven, but will be sustained indefinitely in the columbarium “on a shelf in a concrete box.” If they move to the block apartment building, they will live, but be numbed to life. In this regard, the artists seem equally to contemplate the purgatory of art once it arrives in a museum.

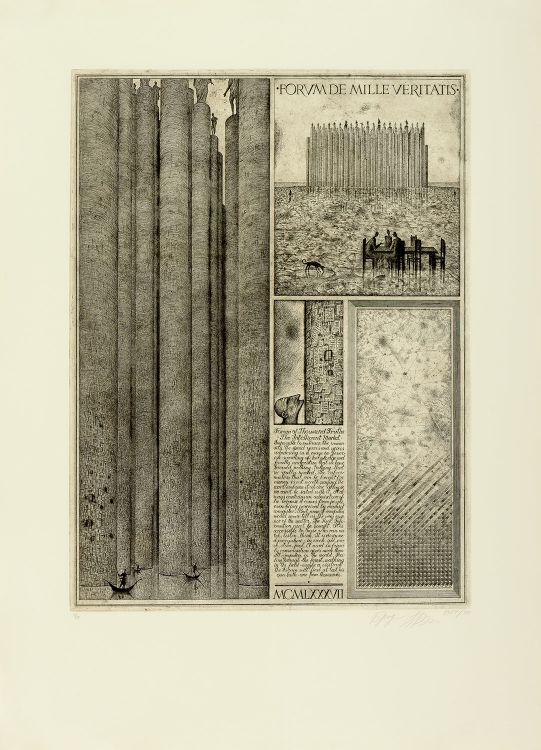

Forum de Mille Veritatis (1987; CAT. 5) moves away from satire and parody of the Soviet Union and takes up the theme of a competition devoted to “The Intelligent Market.” The drawing “was supposed to be devoted to the age of information . . . where all this [computer technology] was taken to the extreme [and] where you could get information in a second from anywhere in the world,” the artists explain. However, they did “not much like all this overload of information,” so rather than creating an etching about technology, they made one about “information coming from other people.”25 The etching contains four sections of various sizes with images that describe a forum filled with magnificent towering columns; a fifth division contains the narrative text. The columns, peaked by different classical figurative monuments, ascend from a sea in which three tiny gondolas manned by miniscule figures glide through deep water. An aerial view reveals the forum to be a large rectangle, one end densely populated by columns, the other completely barren. On the empty side, men sit and talk at a table. A small central box shows a detail of a figure staring up the side of one column, inscribed with various notes and messages that, upon closer inspection, also cover all of the columns. Brodsky and Utkin write that these messages are like the “little advertisements . . . pasted up on lampposts, on the corners of buildings” in cities like Moscow.26

CAT. 5 Alexander Brodsky and Ilya Utkin (b. 1955 and b. 1955), Forum de Mille Veritatis from the portfolio Projects, 1987 (printed 1990). Etching on paper, edition 18/30, 42 x 31 inches (106.7 x 78.7 cm). Collection of the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina. Museum purchase, 1995.12.14. Art © Alexander Sawich Brodsky and Ilya Utkin / RAO, Moscow / VAGA, New York, New York. Photo by Peter Paul Geoffrion.

The enigma of the forum is partially revealed in the etching’s text, “Forum of Thousand Truths / The Intelligent Market / Impossible to embrace the immen- / sity”:

We spend years and years; wandering in a maze of fever- / ish searching of knowledge and / finally understand that we have / learned nothing. Nothing that / we really need. The infor- / mation that can be bought for / money is not worth paying. We / can’t embrace it at one glimpse. / We can’t be sated with it. It al- / ways contains an admixture of / lie[s] because it comes from people, / even being perceived by means of / computer[s]. But [no] computers / would [ever] tell us the very esse- / nce of the matter. The Real Info- / rmation can’t be bought. It is / accesib[l]e to those who can wa- / tch, listen, think. It is disperse- / d everywhere—in each spot, cra- / ck, stone, pool. A word in friend- / ly conversation gives more [information] than / all computers in the world. Sai- / ling through the forest, walking / in the field—maybe a visitor of / the Forum will find at last his / own truth—one from thousands.27

To counter the glut of information in contemporary life, an imaginary forum in which truth cannot be found on columns, metaphors for digital coding is discovered in human interaction:

[P]eople glide through this forest, looking for something. And then they come out onto the shore. On a huge, dirty field full of puddles and muck, there’s a table and chairs, and some people sitting there, completely exhausted by their search. They’re talking. And that information is the very information they need. That’s what the idea was, in a very simplified form.28

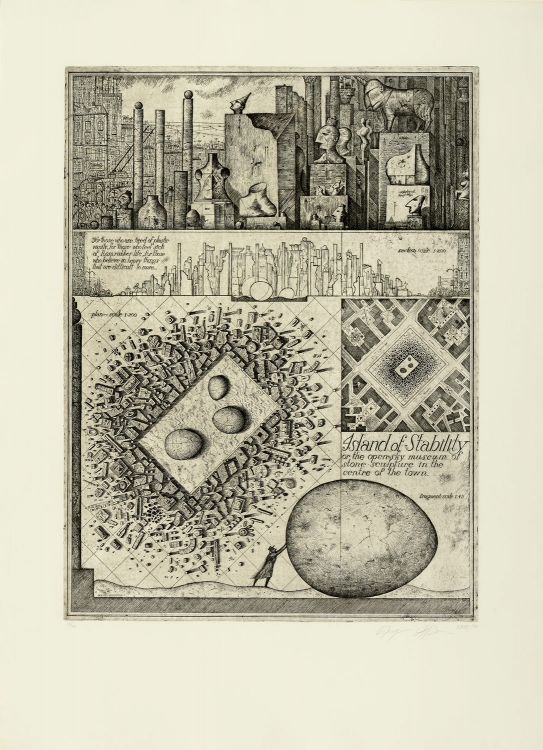

CAT. 7 Alexander Brodsky and Ilya Utkin (b. 1955 and b. 1955), Island of Stability from the portfolio Projects, 1989–90. Etching on paper, edition 18/30, 42 1/8 x 30 5/8 inches (107 x 77.8 cm). Collection of the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina. Museum purchase, 1995.12.20. Art © Alexander Sawich Brodsky and Ilya Utkin / RAO, Moscow / VAGA, New York, New York. Photo by Peter Paul Geoffrion.

“Museum of Sculpture,” the topic of a competition, provided the impetus for Brodsky and Utkin’s Island of Stability (1989–90; CAT. 7) in which they explore the human predilection for prizing the “lightweight, transitory, ephemeral objects clamoring for our attention” rather than the “symbol of something genuine, something stable.”29 Two aerial views of the site show that the museum takes up one square city block, and a central piazza is empty save for three gigantic eggs that represent “a very beautiful, mysterious, magical, natural form that we’ve always felt drawn to.”30 A disorganized jumble of stone sculptural fragments surrounds the eggs. The etching’s divisions offer views of the museum’s contents, which include classical columns and stone busts, among a multitude of other objects, some precariously balanced atop pillars. A bustling city surrounds this stone island. On the edges of the upper divisions are tall buildings, cars, and streetlights with pedestrians milling about. At the bottom of the etching, a man in a coat and hat struggles to push a gigantic egg.31 This image recalls the myth of Sisyphus, the deceitful trickster and king of Ephyre (later Corinth), condemned by the gods to forever push an enormous boulder up a hill, which inevitably rolled back down, requiring the repetition of the command. The text by Brodsky and Utkin on the etching is unequivocal:

Island of Stability / or the open-sky museum of / stone sculpture in the / centre of the town. / For those who are tired of plastic / vanity, for those who feel sick / of foam and rubber life, for those / who believe in heavy things / that are difficult to move . . .32

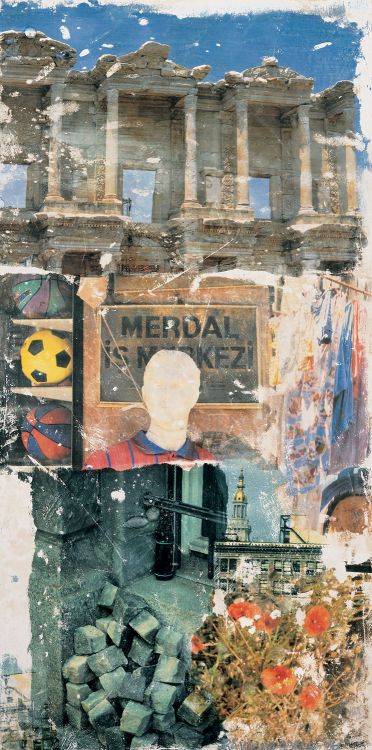

CAT. 89 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), Contest (Arcadian Retreat), 1996. Fresco in artist’s frame, 74 1/2 x 38 1/2 inches (189.2 x 97.8 cm). Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York, New York. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York.

Brodsky and Utkin’s compassion for the struggles of the present in the context of the memory of the past brings them into conversation with the verbal paradoxes of the titles of works in Robert Rauschenberg’s Arcadian Retreat series, comprised of twenty-five inkjet transfer and wax works on fresco panels that he produced in the mid-1990s. The series evolved from a trip he took to Istanbul and Ephesus in June of 1996 when he participated in the United Nations Conference on Human Settlements (Cities Summit).33 The conference considered sustainable urban development, a theme that Rauschenberg explored in his Arcadian Retreat series to which both Contest (Arcadian Retreat) (CAT. 89) and Catastrophe (Arcadian Retreat) belong. In these works, both of 1996, Rauschenberg contrasted the series’ theme with the work’s title to suggest the opposition between an “arcadia” in which life is lived harmoniously, and a “contest” or “catastrophe” in which life is a labor. Rauschenberg’s process of digital printing on plaster panel was a technique he developed with Donald Saff, with whom he had dreamed for thirty years of working in fresco. Despite the highly advanced technological approach, all of the works in the Arcadian Retreat series retain the antique appearance of fresco with its uneven and eroded surfaces. In addition, just as Brodsky and Utkin gave their drawings a sepia-toned and aged veneer, Rauschenberg intentionally imbued his works with an ancient appearance, reminiscent of the fragment of a Pompeiian wall painting that Saff gave to him as a gift in 1995.34 Rauschenberg’s photograph of the Library of Celsus at Ephesus, in the upper register of Contest, seems to refer to the persistent inspiration of the ancient world in the present, such that it becomes the fantasy of an ideal past in the cacophony of contemporary culture. In addition, his placement of a pile of cobblestones — an image that Rauschenberg often used in his work — at the base of Contest reinforces the idea that a sustainable world is built on the knowledge of history. This emphasis also recalls Brodsky and Utkin’s stress on preserving the past in a columbarium (or in an “island of stability”) as a refuge from the present.

Bernice Rose writes that in such works Rauschenberg creates a “cosmos” and “version of Paradise” that represents an “aesthetic instant in which past and present meet on equal terms.”35 But in proposing this rosy view of his work, she misses Rauschenberg’s critical commentary in his oxymoronic titles, and thus fails to grasp that he asks viewers to consider the challenge of making the world a better place based on an understanding of its contradictions rather than on dreaming of a utopian society. Brodsky and Utkin’s message is similar, partnering with Rauschenberg in a realistic, sober view of the contests of the present. Moreover, in their meditations on quality in life, the three artists use inspiring images of architecture as the backdrop for, and elevation of, the otherwise mundane objects of the world. Despite visualizing entirely different histories, contexts, and geographical locales, Rauschenberg, Brodsky, and Utkin address the timeless theme of eternal longing for an ideal world in the midst of the pressing details of everyday reality.

« Previous Essay

Soviet/American Array: Robert Rauschenberg and Soviet Unofficial Artists

Next Essay »

I Am If I Say So, Bob & Bruce