« Previous Essay

Rock Paper Scissors: Materiality, Process, Society

Next Essay »

Soviet/American Array: Robert Rauschenberg and Soviet Unofficial Artists

CAT. 67 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), Audition (Carnal Clock), 1969 (detail)

The history of eroticism in art is as ancient as art itself, and is a story of the confluences of identity, society, and politics, which have shaped and enriched cultures for millennia. While artists have produced an infinite variety of erotic representations, a binary may be identified within this multifaceted genre between subtle strategies of concealment and more conspicuous strategies of erotic confrontation. Techniques of concealment that veil eroticism include serial imagery, fragmentation, and depersonalization of the erotic subject; while techniques of conspicuous eroticism that deliberately expose the body trespass on the interstice between aesthetics and taboo. Yet while seeming to be polar opposites, these two extremes of representation are in fact complicit in the production of erotic imagery, mutually reinforced and charged by gender and sexual differences. Addressing the increasing fascination with erotic imagery in contemporary life, the painter David Salle observed, “Eroticism is the generational word for authenticity,” a prospect that nevertheless, becomes “more distorted the closer you get to it.”1

Robert Rauschenberg understood the paradoxical dynamism of erotic approach (with its diminishing clarity) and erotic avoidance (with its stark lucidity) when he created his Carnal Clock series in 1969. “Part of my project,” he explained, “was about working out my own shyness to photograph my friends’ intimate parts.”2 This comment attests to Rauschenberg’s attempt to grapple with his own erotic identity, that of other artists, and the manner in which to approach and reconcile sexuality in art. Taking the Carnal Clock as a leitmotif for the many derivatives of the sensual gaze, I explore Rauschenberg’s depictions of the erotic in tandem with the genre’s prevalence within the works of Bruce Conner, Andy Warhol, Mickalene Thomas, and David Salle.

Audition (Carnal Clock) (1969; CAT. 67) is one of fifteen kinetic sculptures in the Carnal Clock series. Intertwining vision, motion, and sound, the clocks are embedded with timing mechanisms that recall Rauschenberg’s long incorporation of technology in his work, from fans, lights, motors, and radios in his Combines to collaborating with artists and engineers in Experiments in Art and Technology (EAT), a collaborative initiative involving artists with engineers, scientists, and technology that Rauschenberg helped to found in 1967. The timing mechanisms in the Carnal Clock are calibrated to turn on and illuminate the entire sculpture for two minutes at noon and at midnight. The sound of the self-timing mechanism jars viewers, a sonic alert potently suggestive of something about to occur. Once illuminated twice daily, the clocks starkly reveal the visual material that Rauschenberg silkscreened in a grid onto the reflective Plexiglas panels of each sculpture. Such images include the artist’s own photographic assortment of grainy black and white images depicting both his own and others’ genitals; animals that conjure various sexual associations historically attributed to them (the turtle signifying the penis with its predilection for erect extension or retreat into itself); plants suggesting phallic or vaginal forms; and ordinary objects imbued with erotic implication, such as Rauschenberg’s oft-repeated pictures of fire hydrants. Together such images, illumination, and sound of the works when they turn on and off draw the viewers of Carnal Clock into what Sigmund Freud theorized in 1920 as the juxtaposition between the life principle (Eros), expressed in creativity, species survival, desire, and joy, and Thanatos (the death instinct), encapsulating negativity.3

CAT. 67 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), Audition (Carnal Clock), 1969. Mirrored Plexiglas and silkscreen ink on Plexiglas in metal frame with concealed electric lights and clock movement, 67 x 60 x 18 inches (170.2 x 152.4 x 45.7 cm). Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York, New York. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York.

However striking these images appear when illuminated, they are most commonly viewed during the daily twenty-three hours and fifty-six minutes when only sections of the grid are luminous. During these many hours, viewers primarily see their own reflections on the surface as they overlap with the salacious material below, a facet that compels identification by viewers/voyeurs, inciting their own erotic thoughts. In this regard, Rauschenberg organizes an interactive visual and sexual mise-en-scene in Carnal Clock, such that when caught looking at one’s self mirrored on erotic imagery, desire is unmasked and may be witnessed by others, who are themselves also looking, thereby inducing everyone to become self-conscious about who is looking at whom and why. Rauschenberg himself alluded to the self-inflicted humiliation the works engender, describing the series as a “racy [and] an embarrassing project.”4

The works are indeed playfully lewd and often impel discomfort, a notion that implicates both Rauschenberg and his viewers in scopophilia, or the erotic, voyeuristic pleasure of looking. Moreover, Audition (one of the two Carnal Clocks that Rauschenberg maintained in his own private collection) underscores how he intended the sculpture to entice viewers to try out (audition) their own lustful (carnal) appetites. In mirroring their spectators, the works betray the artist’s intention to expose viewers’ repressed scopic desires, inhibitions, and perhaps even shame. Furthermore, as one must wait for the works to illuminate, Rauschenberg achieves something akin to the effect of a peepshow, one that only exacerbates suspense and viewers’ desire to see the “show.” At the same time, the works further prove that the closer one attends to looking, the more unrecognizable and/or elusive the images of sex and eroticism become.

Once accustomed to Rauschenberg’s playful eroticism, his widespread use of sexual puns and symbols throughout his oeuvre become more apparent, and otherwise innocent images appear saturated with lascivious meaning and content. An open tulip in Angostura (Carnal Clock) for instance, when rotated ninety degrees and placed next to an image of a vulva, becomes a penis about to penetrate the female sexual organ. The images of turtles that often feature prominently in Rauschenberg’s visual vocabulary appear in several of the Carnal Clocks and are repeated in other works like Meditative March (Runts) (2007; see CAT. 90), where his pet turtle Rocky becomes a phallic analog. Rauschenberg also explored the potential for various erotic juxtapositions: crumpled bed sheets and elephant trunks anthropomorphize to connote wrinkled and rough, smooth and hairless textures of the skin and their relationship to the body and a bed as a site of sex; sinkholes and tires suggest orifices for penetration; the hand and pointing finger of the Emperor Constantine in Cy + Relics, Rome (1952; see CAT. 59), juxtaposed to Cy Twombly, conjure sexual acts; Moscow’s Kotelnicheskaya Embankment building and Lenin’s tomb in Soviet/American Array VII (1988–91; see CAT. 85) and the various ancient pillars depicted in Contest (Arcadian Retreat) (1996; see CAT. 89), all might be considered as pictorial metaphors for erections. The fire hydrants that abound in Rauschenberg’s work may be read by some as the “fire hydrant position,” a euphemism for the sexual tripod headstand with legs bent and spread eagle while being entered from either behind or the front. Industrial workmen, uniformed guards, army generals, firefighters, and fire hoses, as in The Proof of Darkness (Kabal American Zephyr) (1981; see CAT. 79) with its phallic hose and lighted blue tip, also recur in Rauschenberg’s imagery.

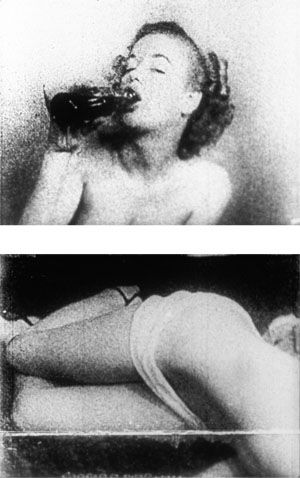

fig. 8 Bruce Conner (1933–2008), MARILYN TIMES FIVE (FIVE PARTS), 1968–73 (stills). 16mm film transferred to video (black and white with sepia-tone tint, sound), 13:30 minute loop. Collection of the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina. Promised gift of anonymous donor, L.13.2012.37. Courtesy of the Conner Family Trust, San Francisco, California and Kohn Gallery, Los Angeles, California. © Conner Family Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, New York.

More significantly, Rauschenberg’s repetition of stock images imbued with erotic connotations achieves subversive affect in the context of his oeuvre and toys with his viewers’ conscious and unconscious erotic associations. This effect is analogous to what the anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss observed about artists’ pictorial repetitions: the willful effort to encourage viewers to search for hidden meaning in a work of art.5 Thus by repeating the conspicuous fire hydrant image, for instance, Rauschenberg alters the perception of this particular useful object, trapping the viewer into equivocating between its obviously innocent connotation and the potential for erotic consideration. This strategy enabled the artist to maintain ambiguity in his art, concealing iconography at the same time as he starkly reveals it. For once one begins to identify erotic images in his art, they begin to appear everywhere. Rauschenberg understood this very well: “I wanted [the works] to grow out themselves, to contain their own contradictions and get rid of the narrative,” he explained, adding that such a process “is the sex of picture making.”6

The “sex of picture making” is equally prevalent in Bruce Conner’s film MARILYN TIMES FIVE (1968–73; fig. 8), which features Arline Hunter, the Marilyn Monroe lookalike and Playboy magazine’s most famous “Playmate of the Month” for August 1954. Hunter was also the star of the 1948 silent film The Apple-Knockers and the Coke (1948), which Conner appropriated and exhaustively edited into MARILYN TIMES FIVE. Conner’s film features the topless Hunter languorously rolling and moving around on a bed as she plays with an apple, both a metaphor for Eve and women’s biblical fall from grace, as well as for Hunter’s voluptuously perfect breasts, or “knockers.” Hunter drinks seductively from a Coke bottle suggesting fellatio, languidly lip-synching to the tune “I’m Through With Love,” sung by Monroe in her renowned 1959 film Some Like It Hot. Conner repeats the song in its entirety five times throughout the film. That repetition is the structure for five slight variations of the same imagery of Hunter in the 1948 film.

The film, the song, Hunter’s body, and her gestures and movements are overwhelmingly seductive and erotic. At the same time, the film becomes increasingly unbearable to watch, even as it is impossible to take one’s eyes off the starlet on the bed. The song transforms the ordeal of the endurance test for the audience into an audition from hell. For every time Monroe’s haunting lyrics taper off, the song stops, only to begin again in mind-numbing repetition, inflecting the film with crippling sadness and empathy for Hunter. Hunter’s role as a mere sex object is reiterated in the lyrics of “I’m Through With Love”:

Why did you lead me to think you could care?

You didn’t need me for you had your share

Of slaves around you to hound you and swear

With deep emotion and devotion to you

Goodbye to spring and all it meant to me

It can never bring the thing that used to be

for I must have you or no one

And so I’m through with love.

Both poetic and tragic, MARILYN TIMES FIVE pays homage to Monroe, who died in 1962. Monroe’s absence adds further poignancy to the erotic estrangement enacted by Hunter. In this way, Conner filters Monroe through several layers of indexical remove, especially in the grainy, degraded black and white footage of the original 1948 film. Hunter is merely Monroe’s doppelgänger, despite her uncanny resemblance to the famous star. The lethargic pace of the song and the film, together with its repetition, are Conner’s techniques for orchestrating an unsettling eroticism that denies narrative closure until the final termination of the fifth iteration, when all erotic content has been flattened out and deadened by repetition, and the prolonged ordeal grinds to a halt. In MARILYN TIMES FIVE, Conner pivots the concept and experience of eroticism on its head, massacring the beauty of Monroe’s appeal to expose the sinister commodity fetishism of her persona, while commenting on the tireless repetition of pornography. Through his artful manipulation of time, MARILYN TIMES FIVE holds its viewers frustratingly captive in a state of arousal and denial.

The phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty pointed out that “perception is not a question of deliberately taking up a position or engaging in a particular act, but a holistic and integrated pre-reflective experience.”7 Merleau-Ponty felt that perception was also “never a static affair, but an active bodily involvement with the world . . . where the body-subject stands in an ongoing living dialogue and reciprocal relationship with its existential environment, of which the symbols of science are merely second order expression.”8 He also argued that such experiences marked “the horizon [that] consists of our previous experiences and future expectations.”9 Taking these observations into consideration, I posit that Conner’s MARILYN TIMES FIVE and Rauschenberg’s Audition (Carnal Clock) together display eroticism that densely entraps viewers/voyeurs in an “audition,” requiring them to negotiate the precarious balance between arousal, discomfort, and the infuriating denial of closure that both works purvey. In this regard, the notion of the audition is subversively manifest in twofold ways: Audition (Carnal Clock) embarrasses the voyeur while MARILYN TIMES FIVE transforms the viewing experience from arousal into that of an endurance test.

Erotic seriality and fragmentation are two aspects of the photographic work of Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol, seductive strategies seen in Rauschenberg’s Cy + Roman Steps (I, II, III, IV, V) and in Portfolio II (I–VI), both of 1952, as well as in Warhol’s four Big Shot Polaroid photographs Nude Model (Male) (1977) and his three gelatin silver prints of Steve Rubell (1982). All of these photographs demonstrate both artists’ use of their cameras as an extension of the eye, or as prostheses for both recording and possessing the object of desire.

In the five photographs comprising Cy + Roman Steps (CAT. 60), Rauschenberg manipulates focal distance and viewpoint to capture Twombly’s descent down the staircase of the Campidoglio in Rome. Gradually shifting the camera angle, Rauschenberg eventually focuses entirely on Twombly’s groin in the last image, leaving the staircase as mere backdrop to his and the viewer’s gaze. A similar effect can also be seen in the six evocative, albeit non-sequential, photographs that Rauschenberg took of Twombly in Portfolio II (see CAT. 61). Four images emphasize Twombly’s hands and his long slender fingers and four attend to his face, both in profile and directed at the camera. Twombly also appears in different clothes: a suit and tie, a work shirt and sweater, and a full-length coat that suggests a cape. Together these two serial works vacillate between the firsthand encounter and its photographic product. In both progressions, Rauschenberg employs a fractured visual language, condensing the desire of corporeal reality into its photographic indexical trace. Temporality and spatiality mutually reinforce each other in order to accentuate the erotic charge between Rauschenberg, Twombly as his subject, and the viewer. Rauschenberg manipulates spatial specificity to erotic ends through Twombly’s various positions and Rauschenberg’s deliberate shifting of focal depth. Moreover, by cropping and concealing Twombly’s face, both in his motion down the Roman steps and in the image of him in a long coat, Rauschenberg accomplishes a kind of anonymous striptease in the former, and conspicuous seduction in the latter.

CAT. 60 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), Cy + Roman Steps (I, II, III, IV, V), 1952. Suite of five gelatin silver prints, 15 x 15 inches each (38.1 x 38.1 cm). Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York, New York. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York.

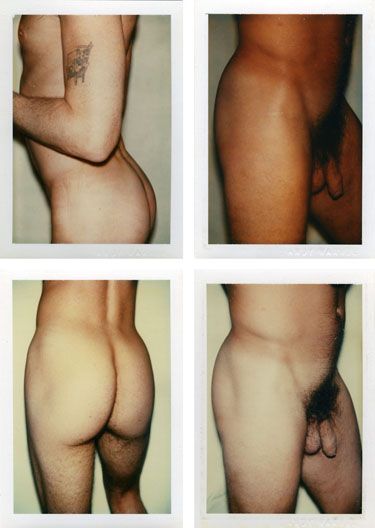

Warhol achieves a similar mode of fragmentation in Nude Model (Male) (CAT. 101–04) through the use of serial images that differ from those of Rauschenberg, notably by Warhol’s conspicuously graphic depictions that strikingly depersonalize the figure. Here, concealment does not arise by virtue of any visual occlusion, but rather through the fragmentation and positioning of the model such that he is rendered anonymous. Nude Model is part of a body of Big Shot Polaroids that Warhol made between 1970 and 1987, and that formed the most consistent thread of his photographic practice from 1976 to 1977. The works satisfied both Warhol’s infamous voyeuristic and scopic drives, as well as his necessity for aesthetic control. The Big Shot camera permitted the artist to simultaneously photograph his subject up close with graphic attention to his body while also remaining aloof, granting Warhol instant gratification. Warhol directly referred to the process of fragmentation in a series of photographic collages he created for Playboy in the 1970s: “You can get close to your subject, one piece at a time.”10

Andy Warhol (1928–1987), Nude Model (Male), 1977. Polacolor Type 108 prints, 4 1/4 x 3 1/4 inches each (10.6 x 8.4 cm). Collection of the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina. clockwise from top left CAT. 101 Gift of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, 2008.9.104. CAT. 102 Gift of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, 2008.9.102. CAT. 103 Gift of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, 2008.9.101. CAT. 104 Gift of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, 2008.9.105. © 2014 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, New York.

In this regard, Warhol’s Big Shot photographs of his model’s body parts become portraits, an impersonal mode of concealment that permitted the artist voyeuristic indulgence without any commitment to an identifiable individual. By attending to the topography of the body desirable to him as a gay man rather than to his sitter’s identity, Warhol accentuated and possessed the man’s genitals, only then to distance himself by describing the images as “abstractions” and “landscapes,” translating intimacy into aesthetics.11 Warhol expressed himself this way in a 1977 conversation with Bob Colacello, editor of Warhol’s Interview magazine, when Colacello confronted Warhol with leaving pornographic photographs on his desk at night. Colacello deferred his own irritation by explaining to Warhol that the images might be offensive “to all the girls that work here.” Warhol responded, “Just tell them it’s art, Bob. They’re landscapes.” Then, holding up a photograph of “fist-fucking,” Warhol added: “I mean, it’s so so . . . so abstraaaaact.”12

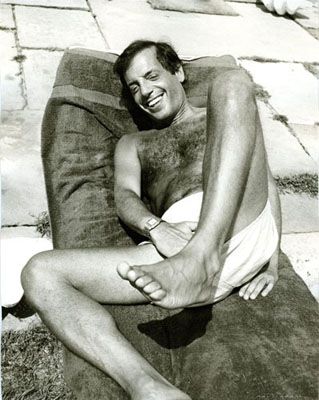

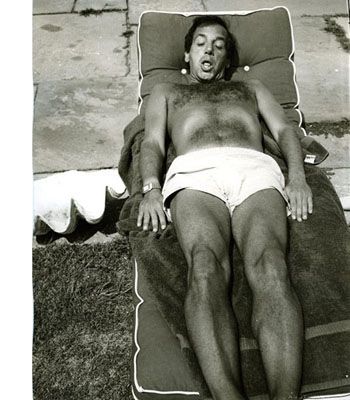

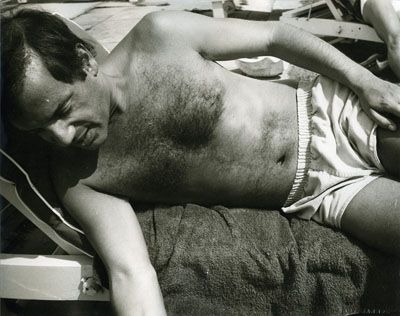

Warhol’s Nude Model series is starkly different from his gelatin silver series of photographs of Steve Rubell (1982; CAT. 105–07) in both form and mode of erotic portrayal. Warhol depicted the strikingly handsome and affable Rubell, entrepreneur and co-owner of the famous New York nightclub Studio 54, in a series of candid views as Rubell reclined in a deck chair whilst on vacation in Montauk.13 Capturing the erotic effect of the bare-chested Rubell in his swimming trunks, Warhol also pictures his confident air of playful nonchalance as Rubell vamps for the camera, glancing mischievously down at his crotch in one image, and covering his genital region in playful erotic concealment in another. Warhol’s prosaic and lighthearted photographs of Rubell convey the sense of their friendship, despite what appears to be Warhol’s pervasive desire for his subject. The Rubell photographs also differ from such singular shots as Warhol’s Unidentified Man (n.d.) and Jon Gould (n.d.), both of which recall Colacello’s view that Warhol “obviously loved men” and that his pictures of men show them to be “pretty extraordinary.”14

Andy Warhol (1928–1987), Steve Rubell, 1982. Gelatin silver prints. Collection of the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina. clockwise from top left CAT. 105 10 x 7 7/8 inches (25.4 x 20 cm). Gift of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, 2008.9.124. CAT. 106 10 x 7 7/8 inches (25.4 x 20 cm). Gift of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, 2008.9.125. CAT. 107 7 7/8 x 10 inches (20 x 25.4 cm). Gift of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, 2008.9.126. © 2014 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, New York.

While Warhol enjoyed the objectification and depersonalization of most of his male subjects, such an approach gave him meticulous control over his expansive photographic documentation, from where to crop a torso to the precise positioning of his subjects’ genitals. Warhol’s control ensured the formal consistency of his photographs and his signature emotional flatness. Adding to this, he argued, no doubt in characteristic tongue-in-cheek manner, “Art should appeal to prurient interests because people are alienated by each other, and porn gets you excited about people.”15

The contrast between Rauschenberg and Warhol could not be starker in so far as Rauschenberg did not self-identify as homosexual, according to the artist’s friend, the curator Walter Hopps, who correctly pointed out that Rauschenberg was “pansexual” and that he “had intimate, long relationships with women, men, his beloved dogs, and the very Earth itself.”16 That being said, Rauschenberg’s photographs of Twombly are “coded, open and closed, public and private, silent and self-expressive,” as the art historian Jonathan Katz has repeatedly insisted in other contexts:

For all of Rauschenberg’s assertions of randomness in his art making, the fact is that there is little that is random about these works, as even a cursory reading of their surfaces makes clear. But given the content of their references, and the McCarthyite cultural context of the time, it’s no wonder that Rauschenberg sought to camouflage his intentions. Queer artists, not surprisingly, did what queers have always done, because it was all they could do, constructing distinctions through the re-contextualization of the extant codes of culture in such a way as to carry affections unrecognized under the very nose of dominant homophobic culture.17

As far as Warhol was concerned, he “refused to play along and be hypocritical and covert” about his sexuality, which “really incensed a lot of people who wanted the old stereotypes to stay around.”18 To this Warhol added: “I often wondered, don’t the people who play these image games care about all the people in the world who can’t fit into stock roles?”19

Rauschenberg deliberately avoided fixed narrative interpretations of himself and his work, and he fiercely protected his private life, while Warhol, by contrast, nourished what he called the “nelly” queer identity of his homosexuality, which he simultaneously paraded and defended, even as he also staunchly withheld information about his private life. Given Warhol’s devotion to making queer reality visible, it is paradoxical that, with regard to their personal lives, and the manner in which identity is manifest in each artist’s work, Warhol was the wild extrovert to Rauschenberg’s decided introvert, even if, as public figures, they were just the opposite: Rauschenberg being vivacious and gregarious, while Warhol being urbanely silent.20

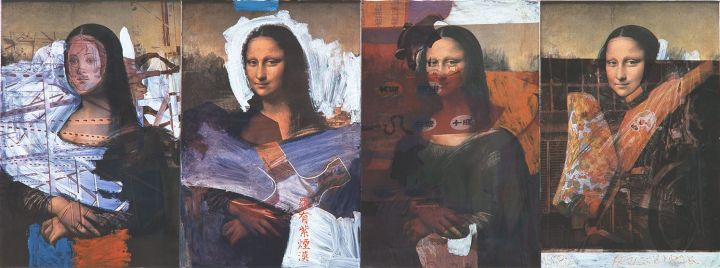

Rauschenberg’s Pneumonia Lisa (1982; CAT. 81) and All Abordello Doze 2 (1982; CAT. 80), two works from his Japanese Recreational Claywork series, have formal similarities, but stage a binary between concealment and confrontation. Both works emerged from Rauschenberg’s brief yet productive visits to Japan on two separate occasions within the same year: from July 15 to August 31, and again from September 22 to October 8. During this time, the artist initiated collaboration with the Otsuka Ohmi Ceramics Company in Shigaraki where he worked with local chemists to produce glazes with which he could silkscreen photographs onto traditional Japanese ceramics. The process resulted in two series of works: Japanese Clayworks, ceramic pieces combined with imagery from ancient and modern Japan printed on photographic decals and painted with glazes and fired at phenomenally high temperatures; and the Japanese Recreational Clayworks, to which both Pneumonia Lisa and All Abordello Doze 2 belong, a series consisting of ceramic paintings in which the artist reworked iconic images from the Western art historical canon such as Leonardo Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa (1503–17) and Gustave Courbet’s Sleep (1866).

CAT. 81 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), Pneumonia Lisa (Japanese Recreational Claywork), 1982. Transfer on high-fired Japanese art ceramic, 32 1/4 x 86 1/2 inches (81.9 x 219.7 cm). Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York, New York. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York.

Pneumonia Lisa exemplifies Rauschenberg’s esoteric mode of erotic concealment, arrived at through a combination of techniques including superimposition, textural variation, and the layering of disparate imagery. The work incorporates four conjoined paneled repetitions of Mona Lisa that include, from left to right, the face of Sandro Botticelli’s Venus from The Birth of Venus (ca. 1486) superimposed onto the face of the Mona Lisa, with the legs of a bay horse protruding from behind the Venus’s head;21 Mona Lisa over-painted with expressionistic brushstrokes, and the conspicuous outline of an oversized hammer over her torso; two photographs of figurines of Japanese Sumo wrestlers that Rauschenberg placed on their side, such that one appears on the bridge of Mona Lisa’s nose; and finally, the full figure of Mona Lisa overlaid with a photograph of the orange fender of a motorcycle playfully decorated with a Mickey Mouse decal. The work is notable for the ironic pastiche with which Rauschenberg imbued each panel, depriving the Mona Lisa of her potent and storied eroticism. By so altering the reception of her image, however, Rauschenberg brings viewers closer to her, severing them from a habitual and inherited reception of the work in order to reintroduce the viewer to the painting.

CAT. 80 Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), All Abordello Doze 2 (Japanese Recreational Claywork), 1982. Transfer on high-fired Japanese art ceramic, 53 1/8 x 52 1/2 inches (134.9 x 133.4 cm). Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York, New York. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York.

In All Abordello Doze 2, Rauschenberg confronts eroticism head on, appropriating Courbet’s Sleep (1866), a painting commissioned by Khalil-Bey, a Turkish diplomat and collector of erotica, who also commissioned Courbet’s The Origin of the World (1866) and purchased Dominique Ingres’s The Turkish Bath (1862). Courbet’s painting was derived from one of three poems about lesbian lovers in Charles Baudelaire’s censored book The Flowers of Evil (1857), and Sleep caused a controversy when it was first exhibited in 1872 for its depiction of lesbian lovers, then unlawful in France. Whether Rauschenberg researched this history or not, he certainly grasped the powerful erotic affect of the sated sleeping lovers in All Abordello Doze 2.

Rauschenberg brings dramatic attention to the women by over-painting, in a flourish of white expressive brushstrokes, Courbet’s detail of an end table with a flower-filled porcelain vase in the upper right hand corner, and by superimposing the pair of Sumo wrestler figurines seen in Pneumonia Lisa over parts of the sleeping women’s faces and torsos. With the latter, he doubles the erotic complexity of the work, bringing the lesbian lovers into a potentially homoerotic situation with the Sumo wrestlers, and even suggesting the possibility of a heterosexual tryst, or ménage a quatre. Finally, the title of All Abordello Doze 2 brings the work into the context of a bordello and the eroticism of sex for hire, as well as into the ancient tradition of Japanese shunga, the term for erotic imagery, which literally means “picture of spring,” a euphemism for copulation.

CAT. 95 Mickalene Thomas (b. 1971), Lovely Six Foota, 2007. Chromogenic print, edition 5/5, 56 1/4 x 67 3/8 inches (143 x 171.1 cm). Collection of the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina. Gift of Christen and Derek Wilson (T’86, B’90, P’15), 2010.12.1. © Mickalene Thomas and Mickalene Thomas Studios, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, New York. Courtesy Lehmann Maupin Gallery, Hong Kong, China and New York, New York.

With the exception of the Carnal Clock series, Rauschenberg maintains decorum even when overtly picturing sex as in All Abordello Doze 2. Similarly, in her Lovely Six Foota (2007; CAT. 95), Mickalene Thomas depicts a statuesque, African American woman seated comfortably in a lavish domestic setting, her blouse unbuttoned to expose the edge of one of her breasts. Thomas shows the woman with her legs wide apart, increasing scopic desire by strategically occluding her genitals in the darkness of shadows. At once the emblem of lasciviousness, reinforced by a posture laden with sexual innuendo, Thomas nonetheless dispels and refutes the African woman as signifier of excessive sexuality by picturing her as aloof, even slightly suspicious with an air of self-possession, a cogent counterpoint to normative phallic-centric and misogynistic images of the erotic female subject in art. Her gaze unflinchingly directed at the viewer, Thomas’s model exudes a confident, even brazen allure tinged with the slightest hint of desire. The artist turns the notion of demure femininity on its head, rejecting the submissive gaze in order to subvert the patronizing Orientalized female, all while presenting her in a setting laden with an array of gorgeous, orientalized colors, fabrics, and patterns.

CAT. 91 David Salle (b. 1952), The Monotonous Language, 1981. Oil on canvas, 72 x 96 inches (182.9 x 243.8 cm). Collection of the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina. 50th Reunion Gift of Tom (T’66) and Charlotte Newby, 2013.20.1. Art © David Salle / Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York.

In striking contrast to Thomas, David Salle’s diptych The Monotonous Language (1981; CAT. 91) is soaked in misogyny that strips its female subject of all agency and places her in a position of extreme vulnerability and perhaps even entrapment. In addition, domestic objects like Eero Saarinen’s “womb chair,” graphically drawn over her womb, assault the female subject; and, with her genitalia pressed into the foreground and legs spread to reveal her vulva, the woman’s contorted pose requires her to crane her head backwards to stare directly at the viewer. She shares the picture plane with a sketch of a household interior reminiscent of the 1950s superimposed on her body, alluding to the erotic underbelly of domesticity. The diptych conspicuously juxtaposes this obscene figurative scene, with a loosely painted abstraction featuring a corporeal pink blob, equally suggestive of the female genitalia.

Salle has defended his work, typified by this painting, under the pretense of the conceptual conflation of irony, paradox, and parody, nonchalantly dismissing accusations that such work is pornographic with the comment that his forms are of an “appropriated sexuality.”22 Salle reiterates his defense of pornography:

The great thing about pornography is that something has been photographed. And what is further compelling about pornography is knowing that someone did it. It’s not just seeing what you’re presented with but knowing that someone set it up for you to see.23

But for her part, the feminist art historian Linda Nochlin has pointed out, “So deeply ingrained are the [binary] conventions of eroticism, that the nude male image . . . connote[s] notions of power, possession, and domination, while the image of the nude female [is] one of submission, passivity, and availability.”24 Salle operates directly in this contradiction, by confronting the male nude as an adversary whose independent existence within all of his art must be assimilated to an intrinsically male desire. By being converted to abstractions, subsumed through layers of superimposition and banal imagery, his female figures are thus enfeebled by these very stylistic manipulations.25 The barrier that these abstracted images creates, between the sensuous immediacy the images purvey and its confrontational erotic charge, resides at the heart of Salle’s title, The Monotonous Language.

In conclusion, I return to Salle’s comment quoted at the beginning of this essay to suggest that eroticism, as a measure of authenticity, remains illusive and becomes ever the more so the closer one approaches. Moreover, erotic display lures viewers/voyeurs into an “audition,” where they must find equilibrium between arousal and discomfort and exhibitionism and voyeurism, as well as a host of binaries that artists intentionally leave unresolved. More particularly, Rauschenberg’s clever use of the word “audition” in Audition (Carnal Clock) ushers viewers into the theater of their most intimate selves in order to undermine and, thereby, transform the experience of viewing into an interactive exchange of erotic selves.

« Previous Essay

Rock Paper Scissors: Materiality, Process, Society

Next Essay »

Soviet/American Array: Robert Rauschenberg and Soviet Unofficial Artists